Raids, Landings, Air-sea Battles and classic Naval battles of the second world war

This section is dedicated to the second world war naval battles, 1939-1945. The conflict was global on even a larger reach geographically (like the asian and pacific front) and fleets were way more balanced, naval battles and campaigns, including amphibious operations or the intensity of the battle of the Atlantic and new theaters of operations.

- 2nd Battle of the Atlantic (1940-44)

- Battle of Hanko (1941)

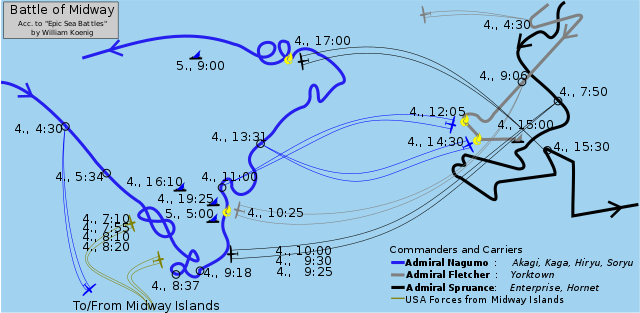

- Battle of Midway (4-7 June 1942)

- Dunkirk (26 May-4 June 1940)

- Operation C3 – Herkules – The Axis planned invasion of Malta (1942)

- Operation Vado (13-14 June 1940)

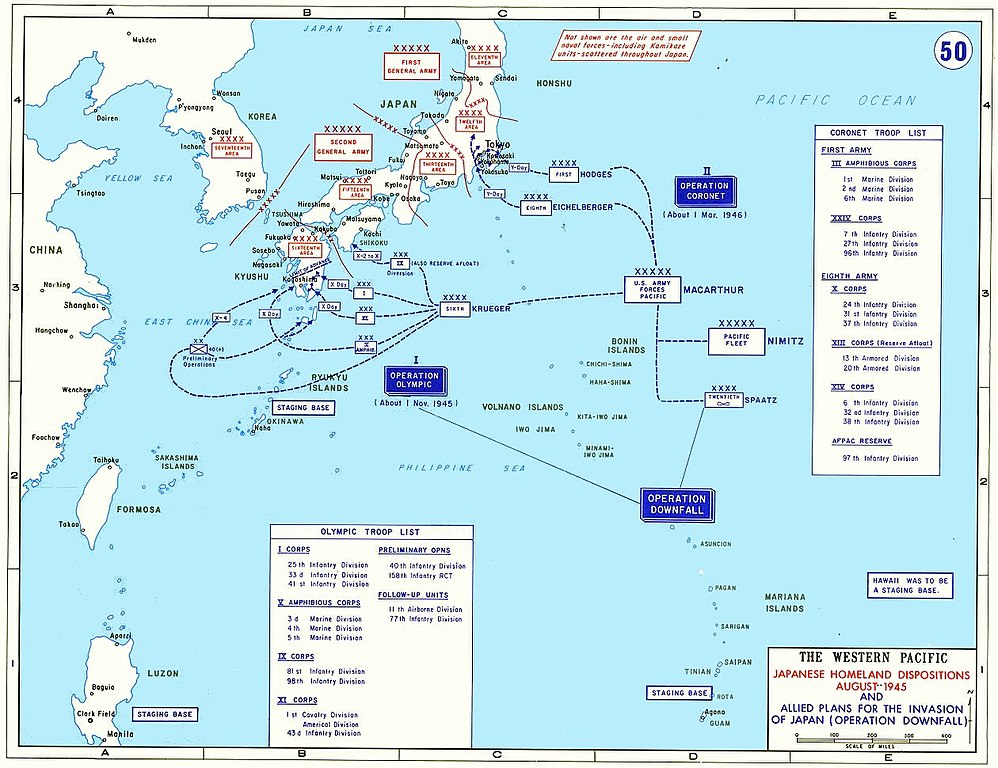

- USN WW2 Amphibious Operations

Summary:

Schleswig-Holstein in Dantzig (1er Septembre 1939)

Graf Spee raid (13-19 dec. 1939)

Norwegian campaign (april 1940)

Mers-el-Kebir (6 july 1940)

Battle of Punta Stilo (9 july 1940)

Tarento raid (11-12 nov. 1940)

Cape Matapan (27-28 mars 1941)

Battle of Kerkenna (16 april 1941)

Bismarck raid (18-27 may 1941)

Battle of Crete (may 1941)

Bataille of the Atlantic (1939-45) Main article

Great Syrta battle (22-23 march 1942)

Pantelleria (15 june 1942)

Operation “Pedestal” (11-12 aug. 1942)

Italian specs ops and Flotilla X-Mas (1940-43)

British Amphibious operations and ships (portal)

Axis amphibious ships and landings (German and Italian)

Malta’s axis invasion plan (Operation Herkules/C3)

Operation Husky (July 1943)

Anzio (Jan. 1944)

D-Day (June 1944)

Anvil-Dragoon (August 1944)

An introduction

This second industrial war, twenty years after the “war to end all wars” saw former naval powers reaching a new height in their development, like the Japanese Imperial Navy. The most crucial aspect was the discrepancy of forces in 1940, after the French defeat: Only the Royal Navy stood, facing the German Kriegsmarine and Regia Marina, while the attitude of the French fleet, neutral but ambiguous, was eliminated in July as a possible threat.

Both the US Navy and IJN remained neutral to this point. In early 1942 however, it was not the case anymore: After crippling the US Navy at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese were free to roam through the pacific, and conquer immense territories in a short period, only stopping short of Australia and India. In this process, the local Dutch and British Royal Navy ships, as well as the Australian navy were also crippled or eliminated altogether. In WW1 both the Japanese and Italian navies stood with the entente.

The central powers mostly counted in the large Kaiserflotte, whereas the Austro-Hungarians and Turkish fleets were quite limited, both trapped in their respective seas, the Adriatic and black sea. The Russian navy was also more considerable than the Soviet fleet in WW2 and due to the territories were largely unoccupied, could take on a more active part in naval operations.

By the fall of 1943 however, reverse started: The Kriegsmarine surface fleet was crippled, limited to Norway and th Baltic, as the Regia Marina, soon to surrender to the allies, while the US Navy stepped into the Mediterranean for a total mastery of this theater.

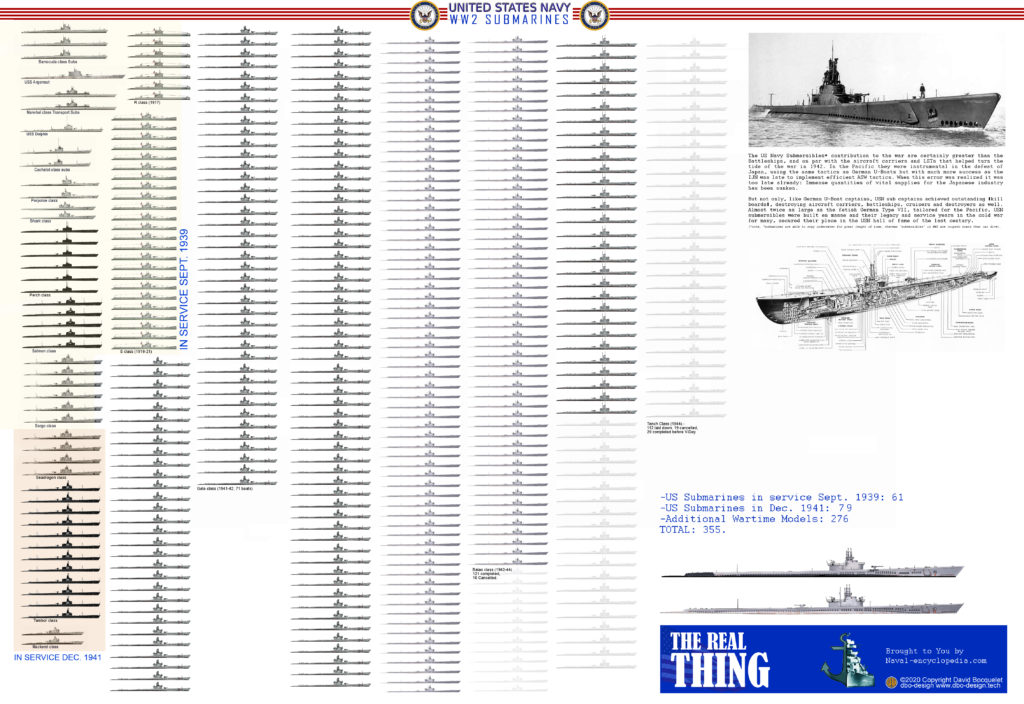

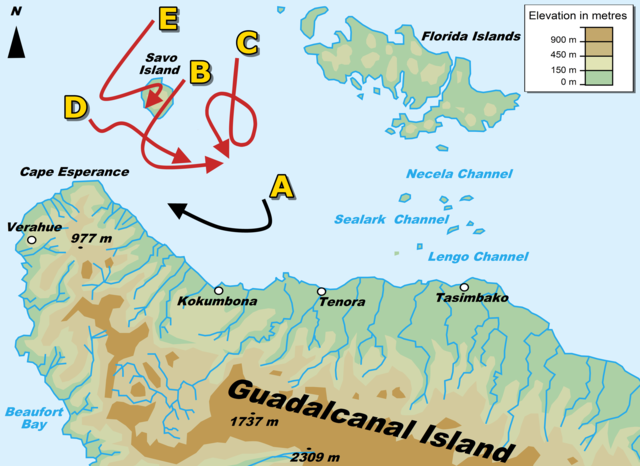

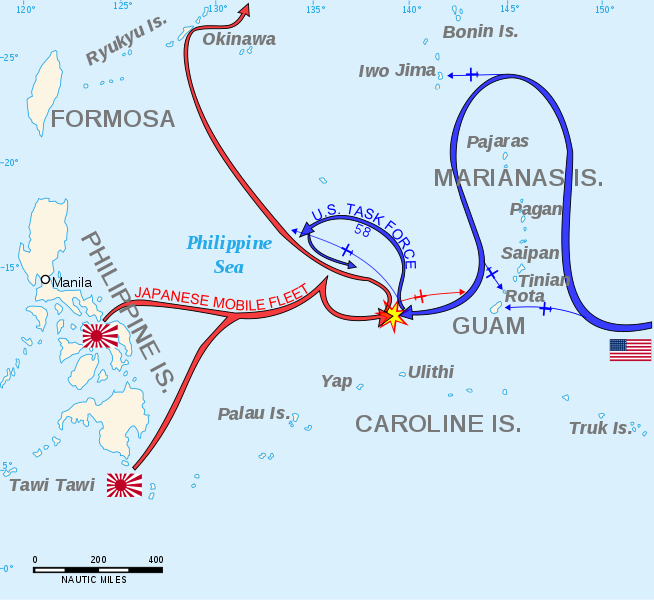

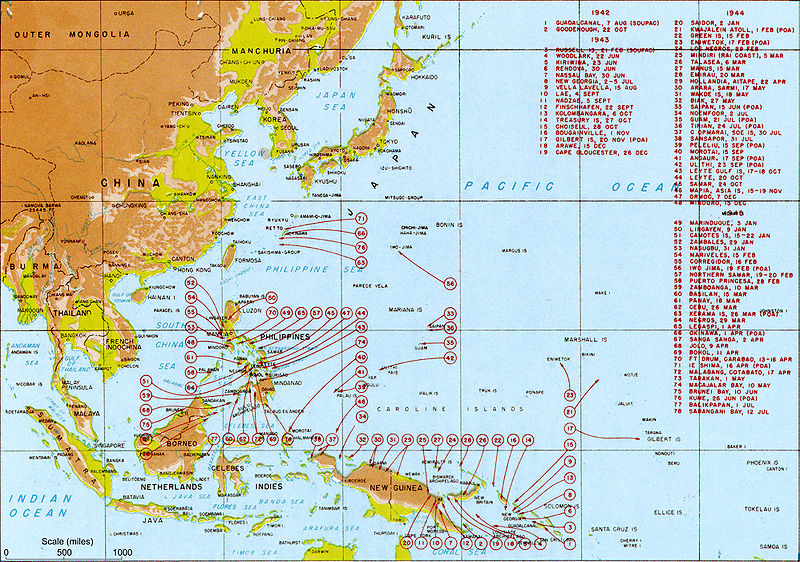

In the Atlantic, the U-Boat threat was better managed, as new escorts were delivered daily by the US, Canadian and British Yards, and losses compensated by even more numerous Liberty-Ships and Victory ships. In the Pacific a slow reconquest of the whole theater began from southern atlantic islands such as guadalcanal and progressed towards the isles of Japan. In 1944 already, the Philippines were taken in the largest naval air battle of the war, crippling what was left of the Imperial Japanese Navy.

From May 1945, the Royal Navy, freed from the Atlantic, could return in force in Asia and help supporting SW asian territories to be retaken.

Differences with WW1 naval battles

Hybrid forms of warfare were what distinguished best both conflicts: In WW1 naval air battles were limited to planes doing reconnaissance over a front or an enemy fleet and amphibious operations were limited also in scale and largely improvized.

The attack on Tsingtao was perhaps the first, earliest combined arms assault, with naval support, aviation spotting, and landings in 1914.

Naval Air Battles

Although all belligerents used seaplane carriers during WW1, only one, Great Britain, pushed the concept up to the first seaborne attack, from the converted battlecruiser HMS Furious. In 1939, nearly all nations had either specialized seaplane carriers and/or aircraft carriers.

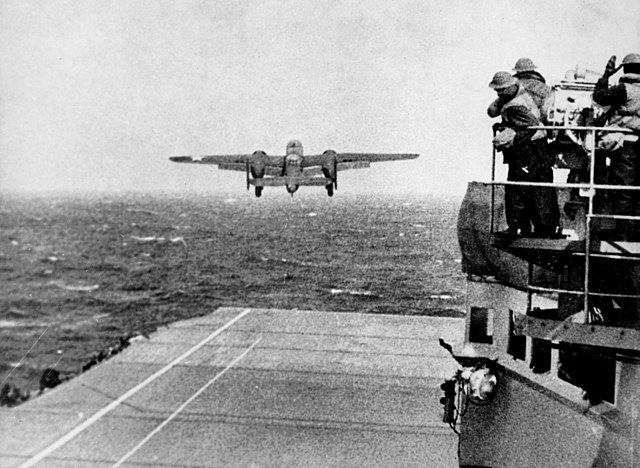

At that stage battleships still ruled, at least the minds of naval staffs around the globe, but the potentialities of naval air warfare were well understood and have ardent supporters in each navy. In 1939, an aircraft carrier could deploy not planes for reconnaissance, which were carried by battleships and cruisers already and made soon obsolete by radars, but rather striking planes, used for an offensive role: Bombers (dive ones in particular), torpedo-planes and fighters to protect them and destroy those of the enemy. The great air-naval battles such as Midway, or Santa Cruz, air attacks of naval bases like Taranto and Pearl harbor were totally new and contributed to place the aircraft carrier as the de facto new capital ship.

Amphibious operations

There was a single well known amphibious landing, at Gallipoli. In reality, many small-scale amphibious landings took place in many parts of the Front but it was nothing near the scope and scale of the great operations of WW2, in Europe, the Mediterranean or the Pacific.

These were complex operations with classic surface ships shelling positions, submarines posted in the flanks for protection, and permanent air cover, while a large variery of assault crafts, boats, landing ships and assault ships were manufactured. If WW1 Gallipoli was a draft, WW2 operations were the real deal, with amphibious vehicles and scores of specialized ships and crafts, mastery of command and control. The USN Task Force of 1945 was the very basis of operations for NATO during the cold war, a reference. All navies soon adopted specialized assault and landing ships.

New technologies

-ASW rocket launchers: Unknown in WW1, they appeared on WW2 escort ships and quickly became more popular than deep-charge throwers

-Radars: Certainly the most advanced detection system, rendering reconnaissance aviation obsolete and playing a vital role in some battles (like at Cape Matapan)

-Sonars: More advanced electronic passive sonars developed after the WW1 hydrophones

-Huff-Duff: Using radio signals for trigonometry

-Computer (Colossus): Breaking German Enigma encoded messages sent to U-Boats greatly helped winning battle of the Atlantic

-Electronic ballistic computers: Analog computers already existed in WW1 but hybridation reached a new height in 1944

-Central Operation: In 1944 in some battleships like the Iowa there was already an attempt to create a central operation, to centralized detection and destructions of air and sea threats

-Anti-submarine missiles: The German deployed in 1943 bombers armed with the HS.31 missile and sunk several ships with it, like the Battleship Roma.

-Helicopters: The IJN used ASW autogyros in one of their ships (Akitsu maru), while some U-Boats carried small rotary wing contraptions or fully-fledged helicopters for reconnaissance

-Assault ships: Designed with a compartment that can be flooded and used as motherships for landing crafts, and the ‘Ro-Ro’ concept of vehicle carrier.

-Hydropters: Developed by the Germans, mostly experimentally.

KMS Schleswig-Holstein in Dantzig (1st Sept. 1939)

September 1, 1939: Fall Weiss (“white plan”) in preparation for months is launched. Backed by a pact with Stalin, and a secret agreement for a joint dismembering of Poland, compounded by the cowardly wait-and-see attitude of Western democracies, Hitler launches his forces against a country whose political constitution dated back only from 1920.

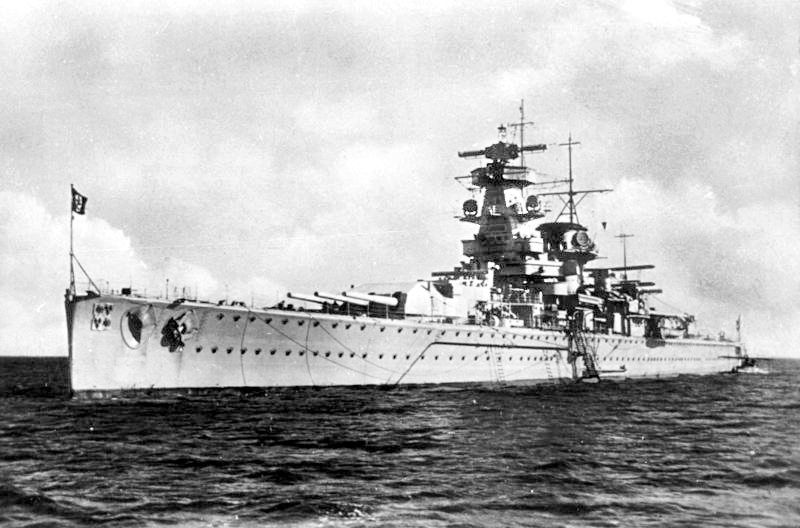

Against the Polish navy, counting only a few destroyers, and under total air domination by the luftwaffe, the Kriegsmarine has a free hand. And the venerable Schleswig-Holstein is sent, a schoolship of the Reichsmarine, from the series of pre-dreadnought battleships of 1905, spared by the allies because of its age.

By the end of August 1939, the commander of the battleship knew what his objective was: Neutralize the arsenal of the Westerplatte, where artillery and ammunition for the Polish fleet were concentrated. The latter is not present, and for good reason: Under the threat of the Luftwaffe, it was preferred to send it to Britain rather than being cut to pieces in an unequal battle, “Operation Peking”.

Therefore no opposition for the old ship was present which coild sail quietly to be positioned in Polish waters, during the night of August 31 to September 1, opening fire at the first light of dawn on the fortifications defending the arsenal. These were reduced to a few 150 mm guns in casemate, that the 305 mm of the German battleship silenced one after another in three hours of time.

The battleship then approached and shelled the installations and warehouses until early afternoon. She then sets off, her magazines emptied, towards Kiel. The Polish Navy was on the run and no longer has a rear base. Polish defense thereafter relied exclusively on the courage of its troops. The navy would fight, however, with exemplary courage throughout the war under British supervision. In particular, the fleet would receive British destroyers and cruisers, renamed and passed under the Polish flag.

Crews were made up of young recruits, Polish sailors fleeing their occupied country. It is disturbing to see how the General Staff casually considered the Polish fleet, to send her an antiquated schoolship that would have been reformed everywhere else, moreover with a crew comprising mostly student-sailors and young officers. Knowing the insignificant Polish threat, and destroyerd airport which paralized Polish aviation, the ship’s departure to the Westerplatte was considered as a simple “shooting exercise”…

The end of KMS Graf Spee

Graf Spee’s raid (13-19 dec. 1939)

19 December 1939: This was the epilogue of the Graf Spee amazing but short career. The German “pocket battleship”, or overpowered cruiser scuttled herself in the Bay of Rio de la Plata. Her commander, Hans Langsdorff, commited suicide a few hours later. It was the end of an infernal chase on all seas for the German raider/Corsair. This affair started with the departure of Kiel of the ship named Graf Von Spee, the third of the Deutschland class, most often described as a “pocket battleship”, by the intelligence services.

Indeed, the mistake came from the fact that these ships, designed in the context of a corsair war were designed by the Germans as “Schlachschiff” even armored ships (“panzerschiff”) on the registers of the fleet, capable of Fight and outclass heavy cruisers while being fast enough to escape classic battleships.

They will be operational at the beginning of the thirties and constituted a technical tour de force because Germany was at that time condemned to not be able to put into service any building of more than 10 000 tons in standard. On this basis, the engineers grafted to a cruiser hull six pieces of 280 mm, caliber able to outclass that of heavy cruisers of the time, but neither in protection nor in firepower these ships could not compete with battleships.

They had been designed to conduct a privateer’s war on allied traffic, with diesel-electric machines – a first for ships of this tonnage, a room dedicated to the collection of seamen of sunken ships, clean refuellers – that of Graf Spee was the Altmark (see below) – and equipment (sheets, torches and paints) to change their appearance as well as make cargos privateers.

The very name of Graf Spee was that of the Earl and Admiral of the Pacific Fleet who, with his ships, led a merciless war on British traffic in 1914 from the shores of China to the South Atlantic, the hero of the first Battle of the Falklands. where he crushed the squadron of Sir Charles Cradock, he perished with his ships during the second battle of the Falkands.

Graf Spee, along with his twins, Deutschland and Scheer, had taken up positions in strategic areas before the start of hostilities. The Graf Spee was with Deutschland and U-Bootes well placed to threaten the traffic of England with the United States, and it will flow, like its twins a large number of British civilian buildings, sometimes with prime targets as a liner Clement on September 30, which causes great excitement (many civilians drowned) in Britain and recalls the old hatred of the “kraut” of the great war and the case of Lusitania.

A week later, all available ships, including French and New Zealand ships, track the Graf Spee from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the Indian Ocean. In the absence of the predator, who continues to make victims, we also look for his supply ship, also masked by dummy registrations.

The Battle of Rio de la Plata (October 31, 1939)

As of October 31, there are no less than 4 battleships, 14 cruisers and 5 aircraft carriers that track the German privateer. On December 2, he sank the big freighter Doric Star. But the track is precise and the last SOS captured the trap is closed.

Henry Harwood thinks that the privateer is now in the perimeter of the bay of La Plata, where the traffic is dense coming from Montevideo.

On December 13, at dawn (6:14), Commodore Harwood’s squadron spotted the German ship in the South Atlantic, off the Rio de la Plata estuary, 150 miles from Montevideo, Uruguay. The Harwood squadron then includes three cruisers, the Exeter, on which Harwood bears his mark, Ajax and Achilles, the latter of the New Zealand Navy.

A three-on-one part will not be easy so far as the large parts of the Graf Spee have a range well above the 150 mm of the two light cruisers English. Only the Exeter 203 mm seems to be able to face the Graf Spee, with the help of his sailors.

This is the “Battle of Rio de la Plata”: On the one hand Harwood does not have an overwhelming superiority, because it lacks one of its buildings, the heavy cruiser Cumberland, refueling at Falklands so close.

On the other side, Langsdorff, who simultaneously spots British ships, thinks the two light cruisers are actually destroyers that escort the exeter. In confidence, instead of taking the field and pounding the ships at a distance, he is getting closer, not counting on giving the British cruiser a chance, while using his 150 mm side pieces against what he believes to be destroyers.

For his part, Harwood has meticulously developed his tactics: He intends to disperse the shots of the German ship by separating his sailors from his ship Exeter, each one on one side of the Graf Spee. At 6:17 am, just as Langsdorff opened fire at 17,000 meters against the light cruisers and realized his mistake, the Harwood squadron responded vigorously and the Exeter shots framed him and some of them hit home.

The Graf Spee wipes impacts without much gravity but disturbing for the future. Understanding the danger, Langsdorff changes course and heads to the estuary of Rio de la Plata, while protecting himself by a release of smoke. Harwood, far from breaking the fight, follows him with every force of machinery.

Langsdorff then began a reversal manoeuver, and deliberately approached the Exeter, concentrating his shot on him and retaliating to the light cruisers with his 150 mm. Very quickly, the Exeter is hit hard by impacts of 280 mm, with a turret out of service and its rudder destroyed. Another impact plows its open footbridge and is a carnage of officers.

The bar answers only through the relay of sailors from the new improvised command post in the engine room. The situation becomes critical, as the Graf Spee gets closer and more fatally adjusts his shots. From the Ajax and Achilles bridges, the Exeter agony is powerless. The responses of the Exeter become very sporadic and are hindered by the smoke.

Even worse, the rangefinders are out of order. Deciding to play his all-out Harwood deliberately approaches for a torpedo, without effect, the projectiles missing their target. He then turns to face his other side and attempt another torpedoing, without further results. For his part, the Gaf Spee accumulates the shots on goal and the Exeter, riddled and almost blind, gives the band. For other commanders, the building is lost.

At 7:40, She moved south and lost contact, but Ajax and Achilles follow her at a distance. Langsdorff decides to continue on his way to Montevideo to repair his damage quickly. But on the spot, it is opposed an obligation to leave the place under 72 hours, according to a law in force governing the parking ships of the belligerents in the neutral ports.

Langsdorff entrusts his wounded to a German freighter who is in the port and his sailors start makeshift reparations, with the small means of the port. Undertakes a diplomatic stand-off to decide to extend (or put an immediate end to) the corsair’s parking in Uruguayan waters. The Uruguayan government does not bend, and Langsdorff is forced to envisage an exit of his ship in the South Atlantic, exit that he fears because his position being known, all the friendly allied squadrons will converge towards the estuary and not leave him no chance.

In fact, at the limit of the territorial waters, stand Ajax, Achilles and Cumberland, which rallied them to any force of machines. Other buildings are expected. The theater of operation (Currently, seen on google earth) On the ground, the Ambassador receives false dispatches announcing the imminent arrival of the Renown and the aircraft carrier Ark Royal.

The case takes an unexpected turn of the media, and a soap opera commented by all news agencies hastened to follow from the port, where thousands of curious people gathered, following the events.

At 18:15, on 17 December, the time had expired, and Langsdorff had his ship sailed. Nobody knows what his building will do. We expect a naval battle on the horizon and many people start to settle on the beach to watch the “show” at night. What we do not know is that Langsdorff has no illusions about the sequence of events.

His ship was not put back in full combat conditions, and he knew his total inferiority. He does not go to the execution but secretly, arrived a mile from the port of Montevideo, has most of his crew transferred to the German freighter that also leaves the port.

He urged Berlin permission to scuttle his ship, but was told no. He therefore prefers not to sacrifice his men and still puts his plan to execution, mobilizing a small team to do. Machines stopped, the warship stopped at 20:50 in the middle of the bay, and a small star leaves him to couple German cargo, anchored not far from there.

And suddenly, a series of explosions tear the tropical wetness of the twilight. The spectators, delighted, attend the fireworks tons of ammunition remaining in the bunkers of the giant. Ravaged by the flames, unrecognizable, the ship ends up sinking slowly.

The freighter brought the crew of Graf Spee to other assignments, but his commander, who had disobeyed the salvation of his men, knew what he was waiting for when he returned to the Reich. For, as he wrote, “to prevent discredit from tarnishing the salvation of Germany,” he committed suicide in his hotel room in Buenos Aires, the first stopover of the cargo ship.

Norwegian campaign (April 1940)

KMS Hipper landing troops on small boats to invade Norway. This was the most important campaign of the kriegsmarine for the numbers of ships deployed (and lost).

At the moment when the Finnish campaign was coming to an end, and the preparations for the great offensive to the west were being made, the German Staff looked upon Norway with interest. This large coastal and mountainous country, poor and poorly defended, was a key position on the North Atlantic, facing Great Britain, as well as an appreciable reservoir of minerals, oil, as well as the famous heavy water needed for research. atomic.

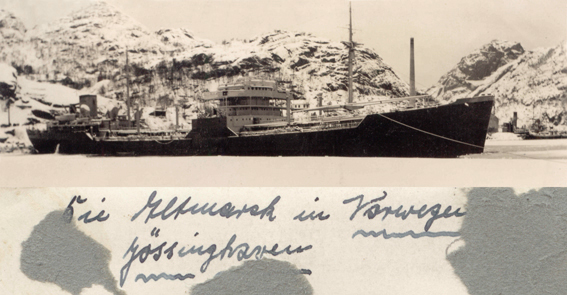

These concerns were recent for the Germans, but already old for allies who sought to weaken the economy of the Reich. For the first time since the “funny war”, allies and Germans would face each other directly. A first warning shot took place on February 16 when the tanker of Graf Spee, the Altmark, was approached and boarded as in the time of the wooden navy by the crew and commandos of the destroyer Cossack in the Jossing fjord where he was in principle quiet, Norway being neutral. The Norwegian government in Oslo protested to the British authorities, whom Churchill called in return “myopic”. This case almost turned to a British-Norwegian confrontation, because the Altmark who had come to find the protection of the Norwegian neutrality saw itself between him and his pursuers the torpedo-maker Kjell.

The “Altmark” incident in 1940 was a misunderstanding between Great Britain and the Norwegian Government because of the neutral waters, and the threat posed by the belligerent German tanker proved to be for British intelligence the supply ship of the corsair cruiser Graf Spee.

It was also the last “old-fashioned” boarding for the Royal Navy, by commandos of the destroyer HMS Cossack. (credits wikipedia) The operation received the green light from Churchill himself, not hesitating to wipe the reaction of the Norwegians. 300 prisoners, civilian sailors captured by the Graf Spee and transferred to the tanker were released at the same time, and the Altmark dynamited. Hitler considered that the waters of Norway were no longer safe and opened a possibility of invasion. On 19 February, the Weserübung plan was outlined. He understood the invasion of Norway and also of Denmark to close the access to the Baltic. Finland was neutralized and Quisling, Norway’s new strongman, showed a complacent neutrality towards the Reich.

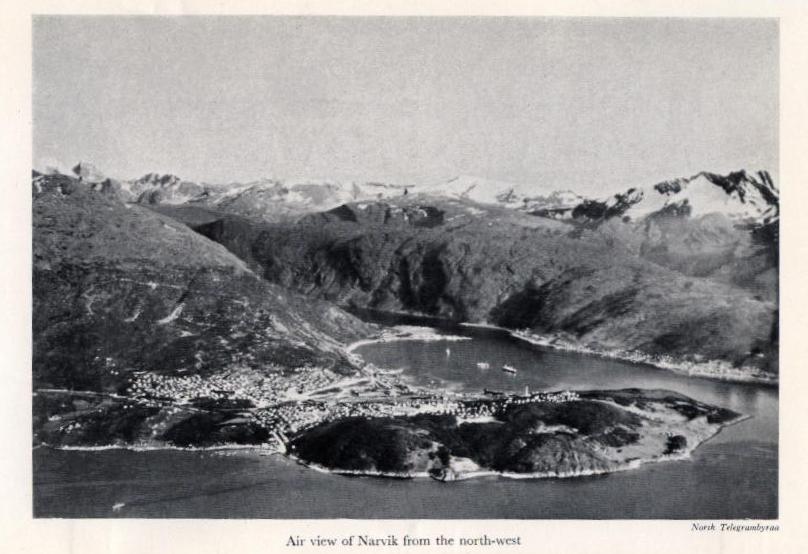

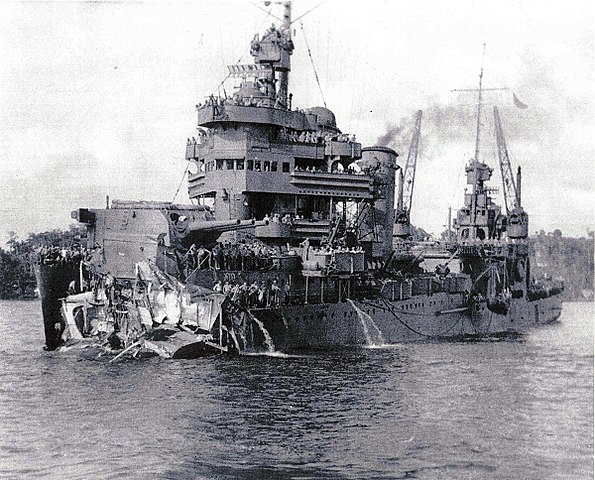

HMS Eskimo after loosing her bow to a torpedo in one of the battles of Narvik

As early as December 1939, with the Russo-Finnish war that began, the allies planned to make Narvik a base of supply for the Finns. But there is a good fear of the Oslo reaction. This does not prevent General Gamelin from forming in January 1940 an Alpine brigade trained to operate in Scandinavia. On March 13, the Allied troops are ready to leave at the insistence of the Finns, who since the 1st have asked for their help. But on this day, the resistance of the Finnish David has found its limits and the peace is signed, the allied operation cancelled.

On March 28, the Allies decide to undermine Norwegian waters to prevent the rail traffic to Germany and occupy the main ports from April 5, but the embarkation of troops and the ordering of convoys is delayed Until the 7th, on the other hand, the ships of the Kriegsmarine leave the Baltic and head for the south of Norway. This campaign both land and sea, because of the nature of the terrain, saw four warring fleets engaged (Royal Navy, French Navy, Kriegsmarine, Norwegian Navy), with feats of arms and major losses on both sides. other.

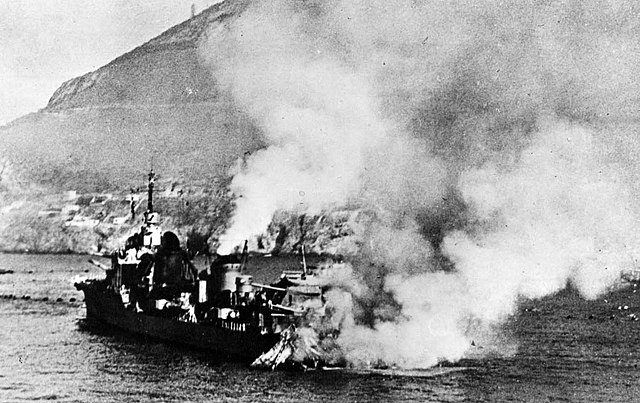

When the Kriegsmarine arrived in order to engage in the narrow passes of fjords to land troops there, they ran into the weak Norwegian defensive capabilities, but it was not the navy that was the danger to the Germans, but coastal batteries. That same April 8, the allies informed Oslo that their destroyers had undermined its territorial waters (in this case the Vestfjord, south of Narvik) to prevent the arrival of the Germans. One of the most famous pictures of the war: The port of Narvik in flames, testimony of the aftermath of the fighting. The memory is painful for the British troops who lived there a “dunkirk” before the hour.

Narvik in 1940

On the night of April 7, a fleet was leaving Scapa Flow to intercept the convoys of the Kriegsmarine. Landings on Norwegian soil begin on the 9th, together with the rapidly consumed invasion of Denmark. The ground forces represent only 7 divisions of infantry and 2 of mountain, with some armored, aviation 970 devices, but for the time all the Kriegsmarine of Raeder is engaged. The deployed forces have 17 warships, but split into two squadrons. That of Trondheim manages to fiddle company with the English squadron by frequently heading course, but is spotted by an English plane which communicates to the fleet this position. Now it was a bait force, which attracts the British fleet and leaves a boulevard to the squadron squadron narvik and Oslo. the operations are as follows: The group that claims to be moving towards Oslo must first pass the fjord defended by old but well placed batteries.

The wing includes the Lützow (ex-Deutschland), 2 cruisers, 5 destroyers and 9 minesweepers, which preceded the convoy. At 11 p.m., a Norwegian torpedo boat defending the fjord was sent to the bottom, but gave the alert, and coastal batteries soon began to thunder. In the middle of the night, they manage to frame the Blücher and manage to sink her. German sailors jumped and swam quickly to shore, fortunately there were few victims. Nevertheless, the precious KMS Lützow is in turn affected and the squadron renounces to continue further. They disembark their troops which then advance along the banks of the Fjord in order to neutralize the batteries. A parachute raid completes the conquest of Oslo itself.

However the Norwegians of the military installations fight like lions and resist until April 13. The Kristiansand Resistance will be just as strong and the city and the port do not fall until the evening of the 9th. A simultaneous airborne operation allows the Germans to take control of Stavanger. The local aerodrome soon received major squadrons of the Luftwaffe. Bergen is also defended by coastal batteries, but the German ship manage to silence them quickly and to continue their progression until the port. There, they disembark and take the place without difficulty. However, British ships in turn entered the Bergen Pass, only countered by the Luftwaffe.

The beached, destroyed German destroyer Bernd Von Arnim, one of the victims of HMS Warspite

At Trondheim, the German squadron passes in front of the batteries without damage thanks to thick coats of smoke; The forces land at the port they take without firing a shot, but the mountain group (Gebirgsjager) will take three days to master the batteries behind. 2000 more of these elite men of the mountain are embarked by 8 brand new destroyers who engage in the Ofotenfjord, where the bulk of what remains of “navy” to Norway and powerful batteries protect the access in Narvik, strategic port if any. On April 9 at 4 am, German elite troops seize the batteries on the back, the rest of the troops chasing the 6th Norwegian Division of the city. The destroyers were quickly right of the few Norwegian units present. On the 9th of April, the axis made itself master of the Norwegian coast; now the Franco-British would try to take them back.

The first action will come from Admiral Forbes, heading a destroyer flotilla on bergen. But the nearby Luftwaffe attacked and sank HMS Gurkha while damaging other ships, forcing Forbes to give up his plan, for the lack of air cover. Despite of this, the Allied Military Council decided to send three more invading flotillas to take over Bergen, Trondheim and Narvik, the main ports of the country. Walburton Lee is sent into the Ofotenfjord at the head of a fleet of 5 destroyers and attacks by surprise the ships present: Two German destroyers are sunk, two damaged, but the other 4 effectively replicate and force it to fall back: Two destroyers are sunk during the latter, including that of the brave captain, killed on his bridge.

With this further failure, the Admiralty decides to use the great means: It sets up a real task force centered around Battleship Warspite and PA Furious, and 9 destroyers. Called “Force B”, this fleet enters this same Ofotenfjord and destroys 5 destroyers, the last three scuttling to avoid capture. Although they do not disembark troops, the British isolate General Dietl’s troops in the harbor itself, who can no longer receive supplies. The reconnaissance reveals, however, that it is impossible to take back Bergen, whose two airfields of the Luftwaffe control the sector. In the face of the Luftwaffe and despite success against the kriegsmarine, the Norwegian campaign was lost to the allies.

Then operation “hammer” against Trondheim started. A naval force was set up, and its direct action was assisted by two diversions at Namsos and Andalnes. The fighting went on inland, Norwegian troops defending valiantly Oslo. On April 13, a bridgehead in Andalnes was established while a brigade landed on the 18th joined the Norwegian forces commanded by General Ruge, but quickly collide in its advance to Lillehammer, to the superior forces supported by the Luftwaffe.

On the 22nd this force leaves the city and retreats to the village of Dombas, an important strategic crossroads. It will maintain delay operations until the 30th, withdrawing from Dombas to Andalnes and being recovered on May 2nd. Until May 30, the last British and French forces, under the guise of naval guns and blocking detachments, and pounded by the Luftwaffe, retreated. The iron road remained open to the axis. This failure prefigured what would follow further south on the continent.

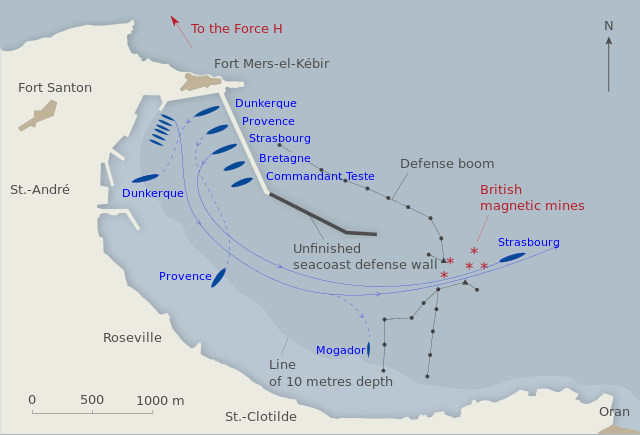

Mers el-Kébir (6 July 1940)

Strasbourg at Mers-El-Kebir

The flash defeat of France was going to plunge press offices around the world into consternation: No one expected anything but a “repetition” of the great war, France to “buffer” Germany, particularly with respect to Great Britain. When the latter fell and the armistice was demanded by Marshal Petain and a certain number of members of the Fourth Republic, England was left to face the axis as well in the Atlantic, North Sea as in the Indian Ocean and in the Mediterranean.

In this last sector, its forces grouped mainly in Gibraltar were inferior to the Marina regia, because the French navy was formerly considered locally sufficient to face it. But since the armistice was requested, despite the opposition of officers including de Gaulle, President Paul Raynaud, and other members of the Fourth Republic, despite the ephemeral project to continue the fight within the “reduced Breton”, then in the heart of the empire, or the national alliance Franco-British, France delivered material and prisoners to Germany.

After these two months of campaign which had cost the French forces dear, the navy was absolutely intact, formidable instrument in the hands of the future government of Vichy. Relations between the signatories, including Petain and Churchill, were strained early on, and they were going to find a definitive breakthrough that would tilt France into a collaborationist neutrality, having passed very close to openly joining the axis with what follows.

For various reasons, Churchill saw the new French government with a wary eye, and still more with Hitler’s future respect for the conditions of armistice. The clauses referred to the disarmament of the German and Italian controlled fleet. His nightmare was to fear the stranglehold of the axis on the fleet.

Position of the ships

This would have had dramatic consequences for the balance of power in a theater of vital operation for England: The Mediterranean. The bulk of the fleet was there indeed, besides buildings stationed in Alexandria, the others were anchored in the bases of Dakar, overlooking the Atlantic, Toulon, and Mers-el-Kebir in Algeria, near Oran.

Of the three weapons available to France in 1939, the navy was by far the most beautiful: The drastic rationalization imposed on the French tonnage to the Washington Treaty, forced it to design buildings directly inspired by the rival naval powers, with solutions clean and innovative. In the end, it was a revived navy, homogeneous, with quality buildings and well trained crews.

A formidable instrument which, unfortunately because of the vicissitudes of the French situation, undergoes an infamous fate. Only a few buildings escaped destruction, either as a result of Allied attacks (US and British) or by scuttling. No gun was exchanged with the real enemy of that time.

The Richelieu (opposite) was the symbol of this fleet, modern and innovative, as the use of semi-automatic quadruple turrets and his “mast-chimney” which was repeated many years later, or the drawing of his bow . The British could not give hope to the ax to seize it, and tried everything, even alienating their former allies.

HMS Ark Royal planes preparing to depart for the harbor

The French ships stationed at Brest had urgently set sail for Great Britain or the French Caribbean Islands (Martinique), others were present at the Saigon base in Indochina. If in one way or another, such as the scenario that almost came to fruition in November 1943, the axis got its hands on the fleet of Toulon and those stationed allier, the imbalance in his favor in the Mediterranean would have no doubt driven the Royal Navy of this sector, with the probable consequence of taking Egypt (not to mention Malta and Gibraltar).

Preventing any reinforcement and closing the route of the Indian and Eastern colonies to Britain, as well as valuable resources of fuel and raw materials. In the face of this disaster scenario, and having exhausted its land forces in France and preparing to fight a desperate battle against the Luftwaffe with a weakened RAF, all hopes rested on the Royal Navy.

The latter was largely mobilized against an exit of the German fleet in the North Sea, in fact, the squadron of the Mediterranean had to fend for itself. After having asked France to deliver her fleet to the British Admiralty, here it is before a dilemma of importance. From June 25, he faces an internal political danger: A fringe of the population experiencing sympathies for the Nazi regime, including some lords, a large fringe pacifist, as in France, give him the obligation to mobilize the population by a strong act, the testimony of a relentless resolution to continue the war whatever the price.

Churchill later wrote in his memoirs that in the dark outlook he faced he remembered the words of the French revolutionaries: “The allied kings of Europe are threatening us, let us challenge them to a king’s head…”. He prepared the operation “catapult” in these outlines at this time. He will still have to face the opposition of many members of the cabinet of war, to whom he barely snatched the approval, and also aroused a living reluctance within the British admiralty: A few months before indeed the French Fleet and British were neck and neck in Dunkirk, Norway, in the South Atlantic to chase the Graf Spee.

On June 13, Churchill and Dudley Pound send a last message to the French government, always to ask the passage of the British side of the French fleet, guaranteeing its independence of action. Churchill is indeed dubious with regard to Article 8 of the peace convention, which states that French ships must be disarmed under the control of Germany and Italy: The term “control” in English a flavor much more authoritarian, equivalent to taking possession. His mistrust of Darlan will only get worse as a result of his participation in the Pétain government.

On June 23 there was de facto a near-breakup of diplomatic relations, the only surviving naval mission of Rear-Admiral Olden’hal, and again the latter was not fully informed by the Government of Bordeaux. Darlan’s refusal to accept and Hitler’s mistrust of speech led Churchill to speed up Operation Catapult.

On June 27, the final plan is approved and begins to run: Admiral Godfroy whose ships are in Alexandria (the Suez Canal is also vital for France because of his possession of the Far East) receives from the admiralty order to rally Beirut. He informed his British counterpart A. Cunningham, who in turn informed him that he had been instructed not to let him leave the port.

On the 29th, France is officially authorized to begin the disarmament of its ships, and the preparations begin sluggishly: The new government wishes to keep the potential of the fleet intact, while on the other hand, the Admiral Darlan made the promise to scuttle its buildings in case of threat of capture by the axis.

On 1 July, Admiral Sommerville, commanding the Gibraltar fleet, was ordered to sail in the direction of Mers-El-Kebir, where the French navy’s largest force was outside Toulon: four battleships indeed are wet. Sommerville sent back a confirmation message as he was reluctant to carry out the mission he had been assigned. On July 3, shortly before dawn, British troops stormed the French sailors barracks and ships in Portsmouth, Plymouth, Sheerness and Falmouth.

There will be one dead and a few wounded on each side. On the side of Alexandria, French and British ships stationed nearby: The British guns were pointed at the French ships (The battleship Lorraine, three cruisers, three torpedo boats and a submarine) whereas the British commander was received on board Lorraine for his birtday, and these ships had their torpedo tubes ready to fire. Fortunately, able negotiations and good sense would prevail in this situation, and confrontation was avoided.

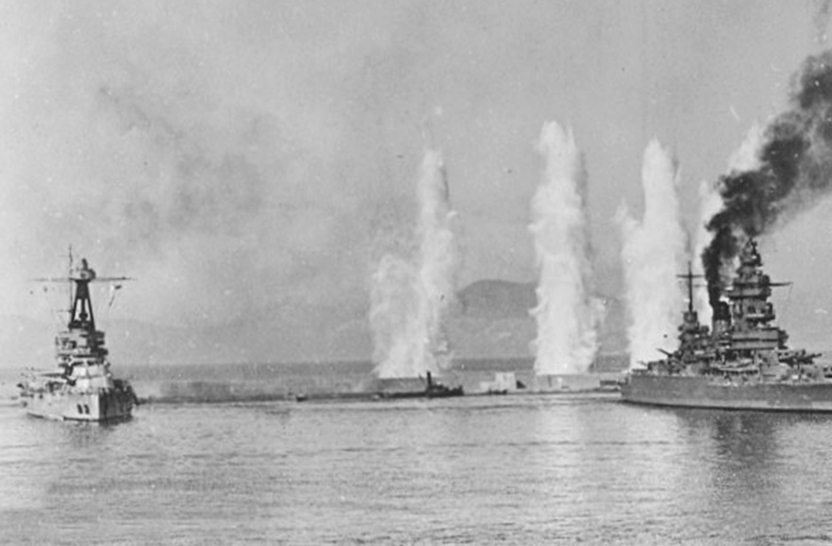

First heavy caliber water plumes, early in the battle

At 8 am Cunningham must send Godfroy the ultimatum to surrender the French ships to the Royal Navy, by a crew pass or to have it disarmed under British control. Negotiations will continue all day. We seek to temporize on both sides. On the other hand, at 6 o’clock, the squadron of Gibraltar, the “H force” of Somerville arrives within range of gun of the harbor of Mers-el-Kebir. It is first Foxhound destroyer, scout, quickly followed by the rest of the fleet.

The latter includes the battle cruiser Hood, the battleships Resolution and Valiant, the carrier Ark Royal, 2 cruisers and 12 destroyers. The French forces present include the Dunkirk and Strasbourg battleships, recent and fast buildings, the older Provence and Brittany battleships, the Cdt Teste airlift, the Kersaint, Tiger, Terrible, Lynx, Mogador and Volta destroyers, all powerful units, plus 15 torpedo boats and 4 submersibles, not to mention the air force.

These forced are under the command of Vice Admiral Gensoul, an Anglophile, who had the privilege of having under his command the Hood during a joint hunt of German raiders in 1939. The British, for their part, had on board HMS Foxhound’s Captain Holland, a Francophile who was a naval attaché in Paris and a liaison officer with the French Admiralty in 1939. Everything seemed to come together in advance to reach an agreement.

At 8 am, after warning the French of a very important communication, a message in Morse Hood says “We hope that our proposals will be acceptable and that we will find you with us”. Then at 8:30, Gensoul receives the British notice, a text written as an ultimatum: It leaves three possibilities to the French admiral: Join the British fleet, sail to Britain for British-controlled disarmament, or drive to the Caribbean or the USA whose neutrality allowed not to violate the armistice agreement.

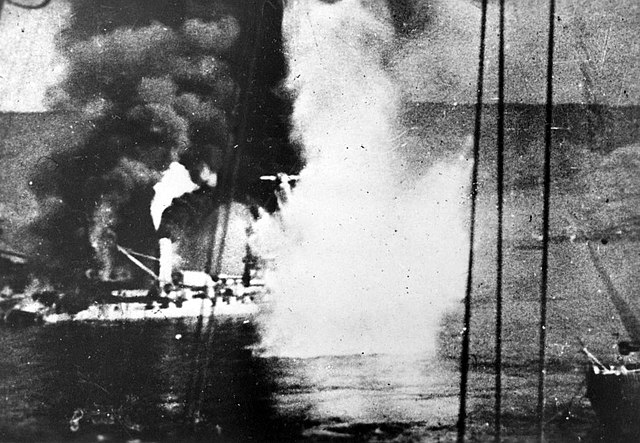

Bretagne is hit

But the spirit of the missive seemed to oppose it. The first two solutions involve violating the armistice convention, Gensoul is forced to refuse. Moreover, the lookouts of Mers-el-Kebir are perfectly aware of the preparations for Force H and the cannons aimed at the harbor. An airplane even took off to observe it and prepare the artillery adjustments. Gensoul gave the order to re-arm the coastal batteries as quickly as possible and to prepare the buildings for a wobble.

He sends a message to the Admiralty, withdrawn to Nerac, in these terms: ‘English force including 3 battleships, 1 aircraft carriers, cruisers and torpedo boats in front of Oran. Ultimtum sent: Sink your ships within 6 hours or we will force you into it. “The admiralty’s response is unambiguous: French ships will respond to force by force” gives Gensoul had in one hand the assurances given by Admiral Darlan concerning a scuttling of the fleet in case of attempted seizure of the axis and had to remained intact, but on the other hand French vessels would defend themselves in case of attack by any opponent, pointing out that the English communication was considered an ultimatum. He refused to receive Holland in person, and his aide-de-camp expresses concerns to him in the event of disarmament under control of the axis: A scuttling could still be possible.

Moreover, through Gensoul’s aide-de-camp on HMS Foxhound, he suggested that disarmament on the spot with the presence of Royal Navy was still possible. But these arguments did not seemed to bend Gensoul, and nothing seemed to be able to prevent the confrontation of arms. Around noon, Sworfish planes of the Ark Royal moored magnetic mines in front of the harbor entrance, seemlingly contradicting possibilities of the fleet to be able to sail to the Caribeans or the USA. At around 12:30, however, Admiral Somerville still reluctant to fire, offered a final conciliation and pushed the ultimatum on his own back at 14:30.

The aides-de-camp on both sides succeeded in persuading Gensoul to meet with Captain Holland. Gensoul believed that disarmament on the spot could constitute a basis of agreement. He however wanted to save time apparently to speed up preparations for combat and equipment, and the British could see them. At 2:30 pm, Gensoul sent a message indicating he agreed to meet Holland in person. This forced Sommerville to extend the ultimatum again.

At 3.15 pm the meeting took place aboard the Dunkirk: It is encouraging: Gensoul gave Holland a text from Darlan, instructions specifying the scuttling of the fleet in case of any threat of capture, and also agreed to start disarmament in situ, but without the immediate threat of the Royal navy, preparations for an immediate departure for the Antilles or the USA were also planned.

However, even as Holland, hopeful of these new developments, was about to report to Somerville, the latter just received from London the message: “Settle the matter quickly, otherwise you will be dealing with reinforcements.” Indeed, Admiral Le Luc, in Nerac, reading Darlan’s message the British intercepted, sailed with his Toulon and Algiers’s cruisers while giving instructions to prepare the ships for a fight. He then informed Darlan of this.

A new communication by Morse is then given from the Hood to Admiral Gensoul, indicating the postponement at 16:30 of the ultimatum, and last deadline. As the British delegation left the Dunkirk at 4:25 pm, 5 min. before expiration, a boat carrying a counterproposal by Gensoul was en route for the Hood. But this was too late. Before it arrived, the admiral opened fire at 16:53.

This was not by any stretch of imagination a “battle” as later claimed in the press, which further scandalized the whole of the French, including De Gaulle, and more a summary execution: The French ships were moored perpendicularly to the harbor, turned inward, so they can’t really defend themselves.

Bretagne is burning

In fact, the two battle cruisers Dunkirk and Strasbourg had all their forward artillery pointing to the shore. In the same way, batteries were mostly turned inwards, to face a possible Italian assault. However they soon turned to the sea and framed the HMS Foxhound, which was obligated to leave fast. The Hood, Valiant and Resolution rained down each eight 16-in rounds every minute, a total of 24 rounds per salvo.

Each salvo raised immense sprays of water, nearly a hundred yards high, falling back with a growl. It was soon apocalypse: Dunkirk was hit on her forward deck, a turret was blown away while the main electric generator and hydraulic system were damaged. The hull was pierced and she took water from all sides. Her commander, to prevent her from sinking decided to make her go straight ahead at full power to beach her. In four minutes the great warship was a steaming wreck with her stern drowned beneath meters of water and her stern raised above the beach.

But the worst was yet to come: The battleship Bretagne, hit the first at 13,000 meters suddenly rose as if by the hand of a titan: Her ammo storages had been reached by a shell. A huge column of flames and mushroom soon replaced her central section. The hull was broken in two, and what was left of the ship capsized and sank quickly, taking 1000 men with her. Provence, which had enough steam, could steam away and clear the harbor, and opening fire on the British squadron as she left.

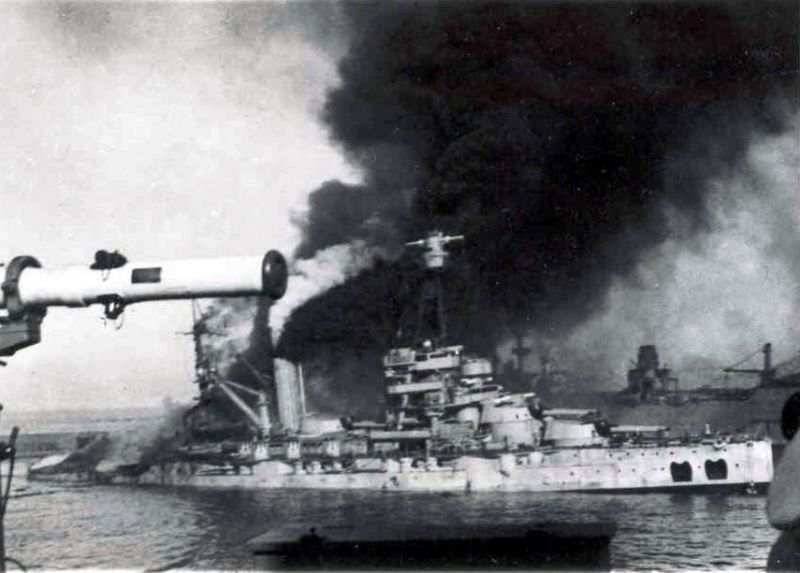

Her salvo near-missed the Hood which responded with a hit on her 340 mm turret, burning her ammunition store below that was immediately drawn to avoid an explosion. The hull was pierced and the engine compartment was getting water from all sides. She went beaching on the other side of the harbor. The destroyer Mogador saw her stern shredded by a hit when she was trying to get out of the harbor. The whole stern section blew up and she was towed to the bottom of the harbor. Other ships, mainly light torpedo boats, were also struck to death. Only Strasbourg, whose trimmers had done the impossible, was able to escape at sea unharmed.

Mogador’s stern is blasted

Strasbourg’s commander cleverly maneuvered behind the Bretagne burning, hidden from British spotters. Miraculously, she passed between the wrecks on fire, swung at the exit between mines at full speed. This was a sailor’s maneuver that even forced the admiration of the British. He managed, with some destroyers, to reach Toulon and Somerville, who was criticized in this respect, gave up following him and finishing him off.

When the cannons went silent, the harbor of seas-el-Kebir gave the awful sight of a field of wrecks burning in huge black smoke. In the midst of the debris, there were tiny white bodies, the dead and the living, swimming back to the beach. What was the spearhead of the French Atlantic fleet was no longer. Still remained the Richelieu in Dakar and Jean Bart, uncompleted in Casablanca. As De Gaulle, who planned a time of his exile in Canada, said, “it was in our hopes, a formidable axe blow”.

Operation Catapult in color

The consequences of the intransigence of the “old lion”, a lack of communication and perhaps arrogance (or another motivation?) on the part of French officers, falling mostly on Gensoul, led to this considerable drama. While the first consequence was to break the remnants of diplomatic relations – already very tenuous – between France and the United Kingdom, this led a large part of the French to be defiant towards the ally of the day before, as traduced by the sytringer resistance of Vichy territories (like at Dakar) to invasion.

Propaganda of the axis received a gift which Goebbels would exploit to the full, almost obtaining the Vichy government from open collaboration to a frank alliance of fact. Subsequently, on many occasions as said before, the French remaining loyal to Vichy showed fierce resistance. The only immediate follow-up of the British attack was an half-hearted raid of French bombers on Gibraltar, without consequences. However in Dakar, the fierce resistance to the R and Free French was fed by “souvenez-vous de Mers-el-Kebir” (Remember…) and this pushed to a near-civil war between Free France and Vichy France, which the most extremist faction grew in power over time, leading to the dreadful Milice and active hunting of resistance movements by the French themselves.

Battle of Calabria/Punta Stilo (9 july 1940)

While the Battle of Britain was raging, the eyes of the world turned to the Mediterranean where Le Duce began a series of campaigns designed both to prove the capabilities of the Italian army against the brilliant success of the Wehrmacht, to annex the Albania and Greece, and was preparing in North Africa, from Libya and Eritrea to start an offensive to eventually seize Egypt and the Suez Canal, depriving Great Britain of this access. vital to his colonial empire to the east. It was in order to guarantee the supply of its armies in Libya to prepare these offensives that the Italian Navy began its operations.

The French Navy is now out of the game due to the armistice and neutralization attacks by the British navy at Mers-el-Kebir, therefore the Royal Navy and the Regia marina were found face to face. In this long duel which was to be concluded in November 1943, the first meeting took place on July 9, 1940, off Punta Stilo, also known as the Battle of Calabria, conducted off the southernmost cape of the Italian “boot”.

Admiral Andrew Cunningham

At that time, the Royal Navy had in the Mediterranean her main fleet based in Gibraltar, locking the passage to the Atlantic, and a squadron in Alexandria, protecting the Suez canal, unique way to the Indian Ocean via the Red Sea. A third lock was placed in southern Italy, at Malta, with the naval base at Valletta.

The Italians, however, had the numerical and technical advantage, the British had indeed relegated for the fleet of the Mediterranean their battleships veterans Queen Elisabeth class (QE, Valiant, Barham), Malaya and Warspite being assigned to the home fleet as well as the most modern of its ships, the two Nelson, the battle cruisers, King George V, and the bulk of the battleships of the Resolution class. Only master card in the hands of Admiral Cunningham, its aircraft carriers, which lacked Italy. The latter had a lot of bases around Italy but no coordination between the navy and the air force.

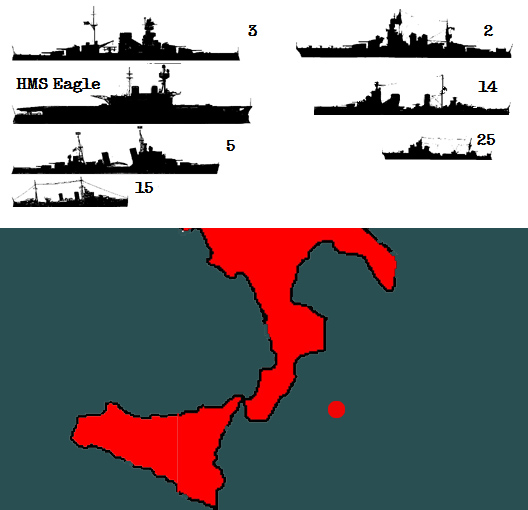

At the beginning of this first encounter, HMS Warspite, after her exploits in Norway, had just been sent to reinforce the Mediterranean Squadron, as well as Malaya and Royal Sovereign. Cunningham could count on six battleships to counter the two Littorio and four Guilio Cesare and Duilio. He also had HMS Illustrious, HMS Formidable, HMS Eagle, HMS Furious in backup. The prologue of this battle will take place in Naples on July 6, because of a convoy to Benghazi made of four cargos escorted by 8 destroyers and 4 TBs. Tripoli was fabricated as a fake destination. The British admiral sent a convoy intended to revive Malta, from Alexandria.

The Italians deployed the bulk of the Italian fleet, a force comprising 6 heavy cruisers, the four Zara and the Trento et Bolzano, 12 destroyers, sent from Tarente and preceding 35 km off the convoy. Behund it followed the Guilio Cesare and Conte di Cavour, 8 light cruisers such as the Duca d’Aosta, Eugenio di Savoia, Attendolo, Montecuccoli, Barbiano, Giussano, Duca degli Abruzzi, Garibaldi, and 13 destroyers. The two squadrons were at the orders of vice-admiral Inigo Campioni joined and converged towards the convoy.

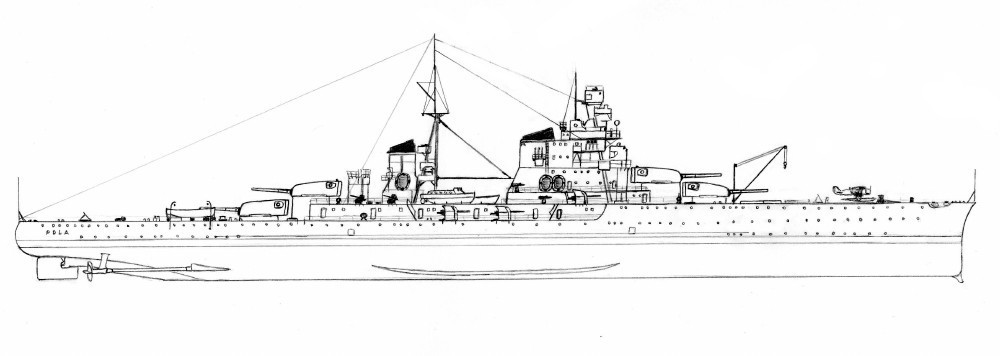

The Cruiser pola

In addition, the first convoy will be separated into two groups of differing speeds (9 & 13 knots) accompanied by three ships, five light cruisers, one destroyer, the HMS Warspite and 5 destroyers on the other. Alexandria fleet with the Malaya and Royal Sovereign armored carriers, bringing you Eagle planes, and 10 destroyers. Dans nuit du 8 au 9, from Italiens destroyers intercepting a message from the RN I planned to intercept the large fleet of Calabria.

Battleship Conte di Cavour

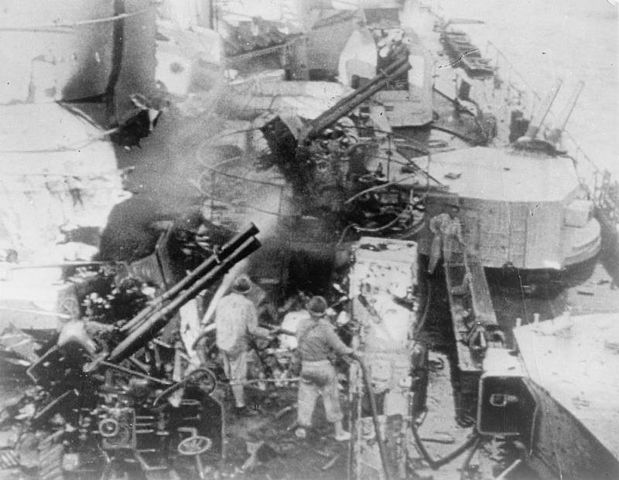

Three destroyers and cruisers removed from the formation went to supply and solve engine issue, the squadron receiving extra destroyers from Tarente instead. The first British convoy was attacked by a gruppo of Sparviero bombers and cruiser HMS Gloucester was badly hit, deprived of any targeting capacity. At this stage, Italian cruisers had the advantage.

On the morning of 9 July, at about 9 o’clock, Cunningham’s leading squadron, including the Warspite and destroyers, was now only 90 miles from the Italian fleet. He decided to slow his pace to wait for the second convoy to be better defended. At 1 pm, Fairey Swordfish of HMS Eagle were in range, and launched an attack against the Italian cruisers, but missed. At 15:15, the two fleets were in visual contact and arrived within firing range.

Admiral Inigo Campioni

The Warspite had been joined by the cruisers that formed a forward screen. The three battleships were far apart but the cruisers were much close close, and an artillery duel began at 21,500 meters, which seemed to turn quickly to the advantage of the Italians whose rangefinders were more accurate. But the better experience of British gunners made the difference and quickly, they could increase their rate of fire.

The battleship Warspite, at the thickest of the action during the battle (here in the Indian Ocean by 1942)

Italian fire managed to close very fast on the cruisers of Admiral John Tovey, who decided in agreement with Cunningham on HMS Warspite, to break off from the fight, right after Garibaldi hit HMS Neptune. At 15:30, cruisers had cleared, giving the hand to the battleships.

Warspite started with the Barbiano and Giussano, but failed to score a hit, as they were too short. Cuningham stopped the Warspite completely in order to give him time to be joined by HMS Malaya, whereas HMS Royal Sovereign was still lagging far behind. Admiral Campioni withdrew his cruisers and advanced his battleships to start an artillery duel at 26,500 meters.

But only Giulio Cesare opened fire at first, Cavour being used as an observer according to artillery adjustment principle drawn from the lessons of the Battle of Jutland, when several ships framed the same target, one needed to determine to which belong the watery plumes. It was finally directed against the Cavour while Cesare concentrated on Warspite. HMS Hereward, a destroyer escorting the Warspite, was severely “shaken” by a long impact of the Cesare. The four heavy Zara-class Italian cruisers then began to fire on Warspite, but Campioni ordered them to retreat with the return of Tovey’s cruisers.

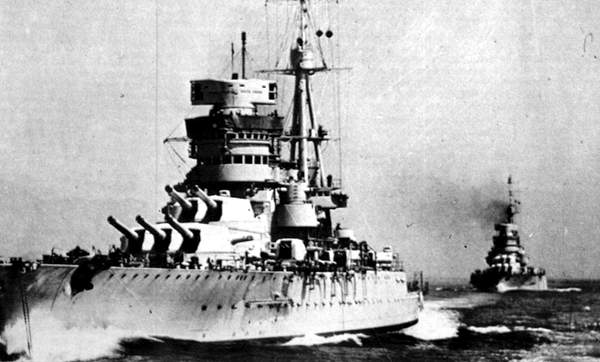

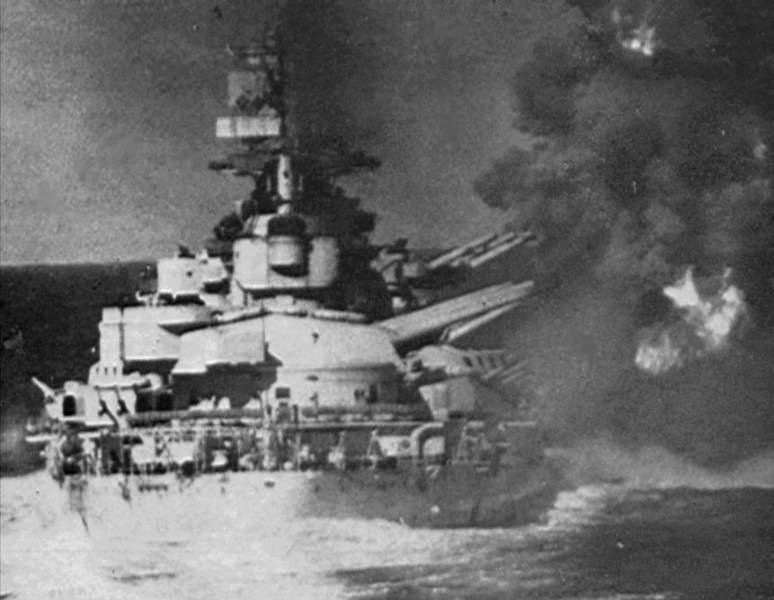

The battlehip Guilio Cesare is firing, photo taken from the Cavour, the observer battleship

The fight turned into a tight duel between Warspite and Cesare. The latter almost managed to hit the warspite, her last salvo flooding her bridges and shaking her hull. But the latter responded with a direct impact at 24,000 meter range, hittin the 37 mm ammo storage. The fire drove the smoke back into the port boiler compartment, forcing it to evacuate. These closed boilers cut down the power available to the ship, which speed fell to 18 knots.

Now an easier target, with HMS Malaya and Sovereign dangerously closing in, Cavour’s captain asked nearby destroyers for help. They launched a barrage of smoke to allow the battleship to slip away while Warspite was still waiting for Malaya to catch up. The latter was now very well placed to seriously hit the Cesare, so his new stop seemed providential to the Italians.

The Guilio Cesare during the battle

When forces regrouped, the Italian fleet deployed its cruisers against those of the British. At 15:58, Italian cruiser line opened fire, Trento targeting HMS Liverpool, but at 16:07, Bolzano was hit thrice with medium caliber (6-in), one damaging the rudder. The destroyer Alfieri was also near-missed and badly shaken. Nearby, Guilio Cesare’s chief mechanics announced at that time that they have repaired the two damaged boilers, allowing the ship to reach 22 knots again.

However, Campioni considering that fighting a battle against three battleships and an aircraft carrier with the unique Conte di Cavour was a too much risk to contemplate, and her decided to retreat the fleet towards Messina, ordering a final torpedo barrage from destroyers to cover it. The British did the same, but no impact was noted due to the distance. At around 16:40, a raid of 126 aircraft failed to score any hit. The battle ended at 16:55, but the next morning, a Swordfish raid from the Eagle sank the destroyer Leone.

Zara firing during the battle

Thus ended the first naval battle between the Royal British Navy and the Royal Italian Navy. Despite considerable resources (almost all the Allied and Italian forces present in the Mediteranean participated), the only loss on the aftermath of the battle was an Italian destroyer. A very thin result for the Royal Navy, but a good test for the regia marina, although other events (fatal for Italy) would occur. There were other approaches and isolated battles before the big battle of Matapan in March 1941.

Heavy damage on the Cesare after the battle

Taranto raid (11-12 nov. 1940)

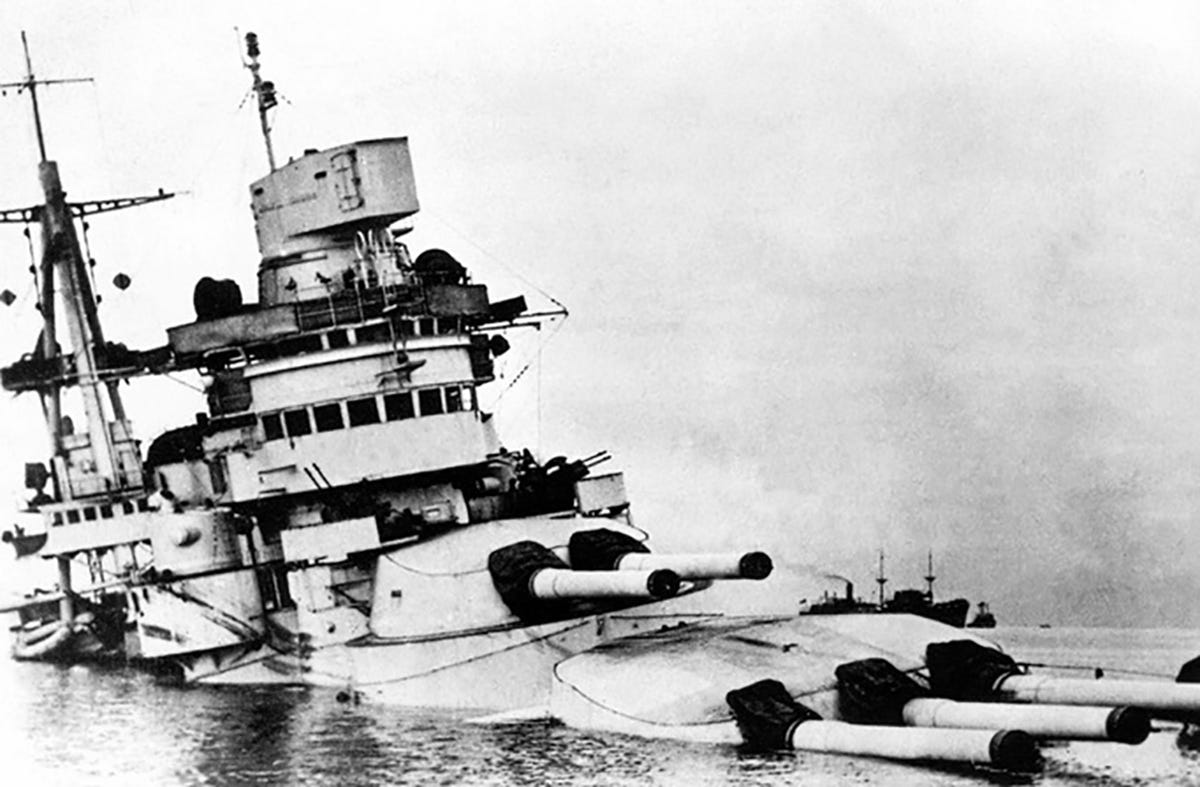

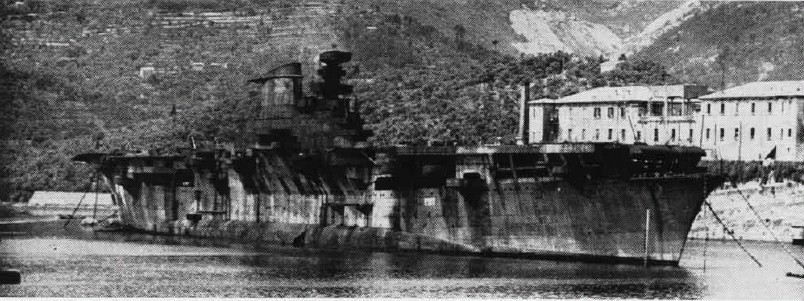

Taranto after the storm: The Conte di Cavour semi submerged. The harbor shallows prevented her to sink completely but she was inactive until the Italian Capitulation.

If the Second World War is fundamentally different from the first, in terms of its geographical scope as well as its dynamics and its industrial massiveness, tactically and strategically it saw the aircraft become a key element: Air attacks were thus conducted with formidable consequences on the various theaters of operation. So it goes from Pearl Harbor December 7, 1941. But this attack was inspired in reality by another, much more modest, conducted with all the audacity required by a Royal Navy ready to do anything to ensure the domination of the Meditannean.

Perhaps the most amazing fact was the disproportionate forces tht effectively hit compared to the result: 6 battleships, 16 cruisers, and 13 destroyers against only 4 cruisers and 5 destroyers on the British side, as well as the old aircraft carrier HMS Glorious and also old torpedo-boats. This is the nature of the tactics used with all the necessary nerve, which would make all the difference and revolutionize the naval war…

Winston Churchill’s resolution along the admiralty were known after Mers-el-Kebir. The naval base of Taranto was a thorn in the British side, menacing communication lines between Gibraltar and Alexandria, and Malta in particular. Maintenaing safe convoys supplying Egypt, just when north african campaign started, was crucial. In November 1940, if Italy suffered setbacks in Greece, it still seemed in a strong position in Libya, and Mussilini’s forces just started a campaign with great optimism. Taranto was in 1940 the main Italian naval base. There, were based all the main warships of the Regia Marina, starting with battleships and the majority of cruisers. Naples and Genoa were mainly arsenals that were bombed by British ships, La Spezia being the second largest naval base and the main Italian shipyard.

The harbor of Taranto was the Pearl Harbour of the Italian Navy, with a roomy, ideally suited area, large fuel tanks, and protected by AA. This was therefore a target of choice, with a formidable strike force composed at that time of 6 battleships, 7 heavy, 2 light cruisers, and 8 destroyers. The British admiralty drew up plans for a first surprise attack called Operation Judgment. It was supposed to be carried out by the HMS Eagle and HMS Illustrious aircraft. The latter was brand new originally for the trafalgar day, October 21, but in the meantime the Eagle was damaged, and it was decided to assign his surviving devices to the Illustrious who would lead the attack alone. The latter deployed four squadrons of swordfish biplanes and was escorted by 2 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers and 4 destroyers, under the command of Andrew Cunningham. It was preceded by twin-engine Martin Maryland reconnaissance flights from Malta, and a Short Sunderland flight the night before the attack.

The plane was spotted by the Italians, but they did not followed suit. That evening, the naval squadron had assembled a few cables from the Greek island of Cephalonia, 170 miles from the Italian base. At 21:00, a first raid of 12 Swordfish arrived on site, followed at 22:00 of 9 others planes. The first, half equipped with torpedoes and the other by bombs, plunged above the harbor at 22:58. These two waves had separated targets, the first attacking the great outer port, and the other half the smaller inner port. The first aircraft marked their targets with flares (which helped the gunners of the Italian AA artillery to down two Swordfish). The attack was carried out with an admirable precision – torpedo planes really arrived at the water’s edge in order to be sure that their gear, modified for the occasion, did not “bounced” or exploded by hitting the bottom which was only 12 meters, which also prevented the Italian ships from sinking completely.

“Dangerous Missions”, You Tube – The Taranto raid

The Littorio, spearhead of the fleet, received three torpedoes, the Caio Duilio and the Conte de Cavour one each. Guilio Cesare was still in repair, withdrawn after the battle of Calabria. The second raid put several bombs on the target, particularly damaging a heavy Italian cruiser. In the end, the balance of the raid was relatively satisfactory: True, the Italian fleet had been deprived for several months of half of its battleships (Littorio (fout months), Duilio (six months), while the cavour was never fully repaired and remained inactive until the armistice of 1943. The fact that this attack was carried out with the torpedoes helped in part to save human lives: Indeed, the Italians had to deplore only 59 dead, mostly prisoners of submerged compartments, and 600 wounded. The British had only 4 losses, 2 airmen killed and two captured. The raid of Pearl Harbor carried out a little later mixed also bombers dive, altitude and torpedo-bombers: the human toll was much heavier.

Regia Marina was then forced to exile to the port of La Spezia further north, and therefore no longer directly threatened the British convoys to the east. The ships needed to mch time to heat up and speed up on the area, the convoys most often were away. Moreover, for each subsequent raid, the fleet was obliged to pass in front of Malta, within the reach of British aviation, always aware of her actions. It can not be denied what was Cunningham’s belief that the Fleet Arm’s “Hour of Fame”, the poor relative of the British Air Force. The coup allowed a frank reinforcement of this corp by many pilots afterwards. On the verge, it was indeed necessary to launch at night such a raid, and it was daring enough to have been made by obsolete planes flying at two hundred kilometers-hours. The Taranto Raid did not meant the end of activities for the Italian fleet, which was going to suffer its most serious setback at Matapan.

Fairey Swordfish

The hero of the Taranto raid, Fairey Swordfish (Image Wikipedia). The Japanese Admiralty, then influenced by Admiral Yamamoto, indefatigable promoter of naval aviation, was going to draw all the lessons of this attack that he would literally plagiarize, with a magnitude increased ten years later…

Cape Matapan (27-28 mars 1941)

Context

Undoubtedly the most resounding British victory in the Mediterranean, the battle of Cape Matapan (actually fought off the south of the Peloponnese ridge), was another very hard blow dealt to Regia marina after the attack of Taranto.

Following this attack, the Italian Fleet one had lost the use of three battleships for some time, especially, had to withdraw the bulk of its forces from this forward base further north and dispersing them between different ports. The present battle takes place just at the end of the Balkan campaign. The British armies just re-embarked and has been not disturbed by the Italian fleet.

The Italian fleet in manoeuvers, circa 1939 (colorized by Irootoko JR)

The next move was initially the attempt developed by the Comando Supremo, in consultation with German forces, to attack troopsships between Egypt and Greece. After a long development, the plan was finalized and launched on March 15 under the command of Admiral Angelo Iachino.

Preparations

A long preparation presided over it and the operation was to be a double offensive carried out both north and south of Crete, starting from four ports (Messina, Naples, Taranto and Brindisi.). It included the battleship Vittorio Veneto, three heavy cruisers of the Zara class, and also the heavy cruisers Bolzano, Trento and Trieste, plus the two light cruisers of the Duca degli Abruzzi class, and nine destroyers distributed in four squadrons commanded by admiral Angelo Iachino, Commodore Legnani, and the admirals Sansonetti and Cattaneo respectively. Quite an amazing deployment of forces.

A long preparation presided over it and the operation was to be a double offensive carried out both north and south of Crete, starting from four ports (Messina, Naples, Taranto and Brindisi.). It included the battleship Vittorio Veneto, three heavy cruisers of the Zara class, and also the heavy cruisers Bolzano, Trento and Trieste, plus the two light cruisers of the Duca degli Abruzzi class, and nine destroyers distributed in four squadrons commanded by admiral Angelo Iachino, Commodore Legnani, and the admirals Sansonetti and Cattaneo respectively. Quite an amazing deployment of forces.

The difficulty came from the fact that the British forces established air bases in Crete, and air support urged by Iachino was theoretical. In reality there was no coordination between the fleet and the air cover, smething tat will plague operations of the Italians in the whole Mediterranean campaign.

Meanwhile, the Luftwaffe’s 10th Corps will bombard Malta while the Regia Aeronautica (Italian air force) as planned would take care of Crete. In addition, submarines have been placed under observation and used for reconnaissance sweeps, following one another at regular intervals over a wide front. They were deployed more particularly towards Suda Bay, the only real gathering place in southern Crete.

Savoia Marchetti SM.79 over Sciacca. The absence of coordination navy/air force proved disastrous for the Italians and later motivated the conversion of two recent liners into aircraft carriers.

The Italian forces set sail on March 27. Weather conditions were bad: The sea was heavy, visibility reduced, but the different groups headed east. In Alexandria, at the Royal Navy HQ, Admiral Cunningham closely followed these moves thanks to his spies and intelligence services, which interpreted the reconnaissance missions of the axis and deciphered coded messages.

The battle

Around noon, a Short Sunderland saw the Italian fleet approaching southern Greece, and immediately Cunningham gave the order to Force B under the command of Admiral Pridham-Wippell, to set sail from Piraeus and stand behind the island of Gavdos (southwest of crete) and be ready in March 28.

For his part Cunningham fooled the naval attaché of Japan, who spied the British in Alexandria on behalf of the axis, that he was to leave to rest, taking his golf clubs with him when in fact would later later embark during the night and set sail with the bulk of the British naval forces in the east.

The next day around 2 p.m., Iachino was aware of the detection of his fleet after having intercepting a message from the Sunderland after spotting them. As he feared to see himself outnumbered, he ordered his forces to cancel the operation the north of Crete, and to regroup in the south. At dawn, Vittorio Veneto’s reconnaissance planes spotted Force B (Pridham-Wippell) east of Gavdos. As this one included only four cruisers (Ajax, Gloucester, Orion, Perth) and four destroyers, he knew himself in a position of strength and lashed towards the latter. As expected, Pridham-Whipell, after a brief duel from 7.45 am until 8.30 am, withdrew towards the main body of Cunningham’s forces. The classic manoeuver.

Cunningham from his part was at the head of three battleships, the Warspite, Valiant and Barham, followed by the aircraft carrier HMS Formidable and 9 destroyers. Although having a large numerical superiority, the Italians of Admiral Sansonetti’s squadron (the three cruisers Bolzano, Trento and Trieste) failed spot British convoy as Visibility was so poor.

Sansonetti decided to abandon the chase and turned around to return to Vittorio Veneto (Iachino). Pridham-Wippell also turned around and kept in touch with the Italians. This was the time. Sansonetti’s cruisers joined Veneto at 10 a.m. and together opened fire again on British cruisers, who started a second manieuver which almost turned into a rout: The large calibers of the Veneto closely framed them, and those of the heavy cruisers too. The light 6-in guns of the cruisers could not compete and they only survived by deployming an intense smoke curtain and by skillful maneuvers.

It was now around 11:30 am, and the Italians gave up on it and headed north-west. Suddendly, rushing from the sky, a group of Fairey Albacore torpedo bombers from HMS Formidable attacked ihis ships, but without scoring a single torpedo hit.

Iachino felt his forces were now vulnerable especially the vitorrio, now the last operational battleship, and the absence of advanced air cover, decided to withdrew. Shortly after, Force B joined the Cunningham fleet and informed them of the composition of the Italian squadron. His old battleships being too slow to catch up, he had the Fleet air arm ordered to slow down the Italians and renew attacks.

At 2:00 p.m. bombers from Crete bombed the Italians at high altitude, but without results. The latter headed to Taranto, hoping for a rapid intervention by the Regia Aeronautica meanwhile. A new attack on HMS Formidale occurred at 3:20 p.m., practically at the same time as high-altitude planes just captured the attention of the AA crew. Attacking from just abive waves, they rushed almost without being spotted and socred a hit on the Vittorio Veneto, at the port propeller.

This caused a very serious damage: The bar was now blocked, and 4,000 tons of sea water rushed into the engine rooms whose compartments were evacuated. Her engines were stopped, and the Veneto was now dead in the water. Iachino’s worst nightmares were not realized. Mechanic teams reushed into action and will then do the impossible to allow the ship to leave before Cunningham arrival: Their struggled would take half an hour. This ws the Italian heroics of the day, showing that well trained maintenance and emergency tems can save the day, like at Midway.

Vittorio Veneto started painfully to reach 16 and then 20 knots, a miracle which was enough to outrun the dangerousely close British battleships. To save his flagship, Iachino had her framed and protected by a AAA curtain with all his heavy cruisers. These, opening fire and blinding British pilots of the third wave with their projectors at full power, almost routed them, shooting down one in the process. This was the only loss of the battle, showing that Italian AA was certainly not the best at that time. Nevertheless, one of these planes of the third wave scored a hit on the Pola. This was the hinge of the battle, the moment of truth. It was then that the chief admiral made an unfortunate decision.

Ignoring that the bulk of Cunningham’s forces are approaching (the Italians had no radar, unlike the Rpyal Navy – this will weigh heavily in the balance of the battle), Iachino ordered Zara and Fiume to protect and tow the Pola to safety back to Taranto while he plan to strengthens its forces and return. At dusk, the Pola is effectively joined by the Zara, at the head of the line, followed by the Fiume and the destroyers, at low speed.

At 10:25 p.m., Cunningham, closely monitoring the Italian moves by radar, approaches by night, all lights off. The Italians ignore everything about the proximity of the British battleships until they are only at 3,500 meters. By then, order is given to turn the searchlights at full power on the Italians. Time stops for a second; And the batte line then open a deadly fire: In a few minutes, the three heavy cruisers are no more than floating torches, badly hammered by 15-in HE shells. This is a harrowing sight.

The Fiume is wrecked by explosions, list heavily, and sinks in a few minutes, carrying with her, almost the entire crew. Zara is widly blazing but refuses to sink, and the Pola, also burning from stern to stem, is undoubtedly the least “battered” of the three. On board there total panic. Completely bewildering by what just happen, the crew did no longer obeys their officers. Some jumps to the water, others (as reported later the the British boarding party) is drinking alcohol and behave like the end of the world was near. The destroyer Jervis, aking advantage of this situation indeed approach the Pola without being worried and land a company of infantry to take the officers prisoners and possession of the ship in a few minutes.

The crew of Pola, Ionian Sea, 1940.

Epilogue

The battle of Cape Matapan is perhaps one of the best remembered naval battle of the Mediterranean. It is showing grave deficiencies in the Regia Marina, both the lack of radar, and absence of coordinated air cover, which mussolini himself had to admit. The results of this last act of the battle are quite serious for the Italians who lose three heavy cruisers, considered the best in the whole fleet, along with two destroyers, the Oriani and the Carducci. The last operational Italian battleship after the disaster at Taranto, the Vittorio Veneto, is also immobilized for long repairs.

The Zara went on to burn, listing on her the port side up to the next day. She will be torpedoed by the destroyers of the 14th division (Captain Mack) while Pola was towed to Alexandria as a war prize, something quite unique in WW2, and a supreme humiliation for Mussolini. The British press went wild about this success and Churchill had at least something to positive to present to the house of commons.

But Cunningham was criticized to quit the area back to Alexandria, perhaps too soon, because of the still latent threat of Axis aviation. The Pola was torpedoed and the survivors picked up by the hospital ship Gradisca. The battle discouraged the Italians from other large-scale actions for long unless they can make better use of naval aviation or developing or adopting a radar (via Germany). The lesson was digested enough by Mussolini that he returned on his previous opposition to built an aircraft carrier, boasting Italy was itself the best, unsinkable carrier around. Order was given to start the reconversion of two liners, the Aquila and Sparviero, into aircraft carriers, while a commission was charged to bring from Germany engineers and equipment in order to equip the fleet with radars.

Battle of Kerkenna (16 april 1941)

This apparently less important naval commitment was nevertheless a perfect illustration of the purpose of naval battles in the Mediterranean between 1940 and 1943: To allow the supply of the troops of the two camps engaged in Africa. Kerkenna is a series of islands surrounded by shoals on the Tunisian coast. A squadron of British destroyers, without any other more important building, is urgently sent to intercept an Italian convoy of 5 freighters escorted by 3 Italian destroyers, bound for the Italo-German forces which besiege Tobruk.

The convoy includes the German freighters Aegina, Iserlohn, Adana, Arta, and the Italian freighter Sabaudia, escorted by the Tarigo, the Lampo and the Baleno, all under the command of Lieutenant Da Cristofaro. Commander Mack’s 14th British squadron from Malta included the Janus, Jervis, Mohawk and Nubian. These last two were of the “tribal” type, very powerful. This very simple interception action, also called the battle of Sfax, was broken down into two stages.

Italian destroyer Lampo

At first, the British destroyers spotted by radar around 1:00 am the escorts of the convoys and opened fire from a good distance (The Nubian and the Mohawk in particular had 8 long-range 140 mm guns, completely outclassing the Italian artillery). The artillery duel turns very quickly to the disadvantage of the Italians, who take several impacts, but the Luca Tarigo will have time to get close to its attackers enough to release a line of torpedoes, before being permanently disabled.

Regia Marina (Cdv. Mack LdV Da Cristofaro)

3 Destroyers

3 Destroyers

Royal navy (Andrew Cunningham)

4 Destroyers

4 Destroyers

5 Cargos

5 Cargos

The British destroyers maneuvered to avoid them, but the Mohawk was struck and badly hit by two torpedoes. Helisted quickly, but without sinking, he was no longer able to make his way to Malta. Second, the British destroyers meticulously torpedoed the Axis freighters, sending them all to the bottom. After the battle, the destroyers saved the crews, but the Mohawk, which had lost 41 men in the double impact, was scuttled before sinking. In the end the action was successful on the British side. The convoy was a precious help for Rommel’s troops, 3,500 tons of material, 300 vehicles and 1,800 men (out of 3000) lost, fuel, food, reinforcements which were sorely lacking.

Bismarck raid (18-27 may 1941)

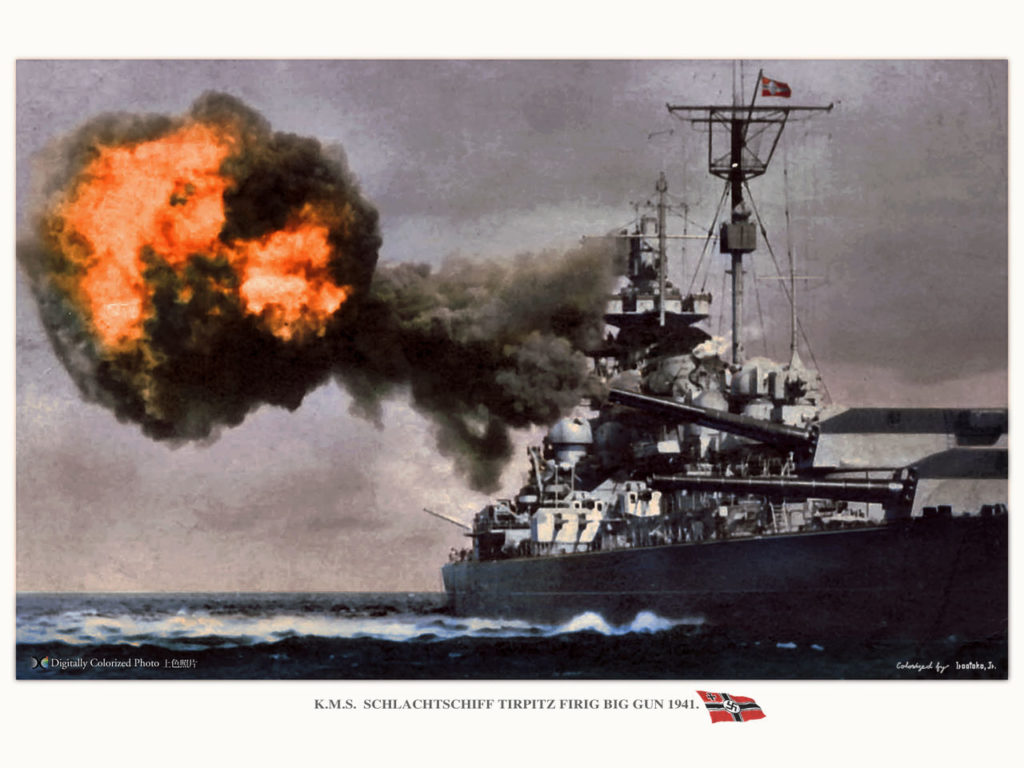

The Bismarck Affair (May 18-27, 1941): The most famous photo of the most famous battleship: The titanic Bismarck opening fire on the unfortunate Hood.

“Sink the Bismarck”. By this peremptory order of Winston Churchill, which gave rise to a film with the identical title, half of the Royal Navy was dispatched with all business ceasing – including convoys from the Atlantic – from Scotland, from the Firth of Forth, but also from the east coast of England, or even Gibraltar. All these forces against one ship: The German battleship Bismarck. This means that the threat he represented for the “old lion”, well informed by his naval attachés.

It all began with the project, within the Kriegsmarine staff under the patronage of Admiral Raeder, to provide Germany with a real battleship, since the blank check granted by Great Britain in 1936 , which at the time sought to appease the master of the Second Reich by allowing him to build a fleet with a tonnage representing 25% of the Royal Navy. Sweeping aside the Treaty of Versailles, in particular the ban on building ships over 10,000 tonnes, which a priori banned battleships, Hitler and Raeder set up a very ambitious program aimed at returning to the Germany the naval force it had in 1914, then the second largest in the world. But to get there, a long road was to be expected, and the plan was not to be fulfilled until the 1940s.