Alaska class large cruisers (1943)

The Alaska class were the “great white elephants” of the US Navy in WW2. Their conception went back to the start of the war, when limiting treaties became obsolete, based on a rumored IJN “cruiser killer”. The US Navy studied a new standard of “large cruiser” by default of a better terms. Some even dubbed them “battlecruisers” but there is now a consensus they were just their own thing. The Japanese B64 projected super-cruisers were never completed, nor the German P-class in Z plan, leaving the three Alaska class pretty solitary worldwide and in US service, seeing little service in WW2 as well as postwar due to their enormous maintenance cost. #ww2 #usn #usnavy #pacificwar

USS Alaska, colorized by Hirootoko Jr.

Design Genesis

Origins going back to “treaty cruisers”

It’s a long debate, but which had been still not fully settled to this day: How much the conventional treaty cruisers impacted new warfare concepts in the interwar, due to the ban on new battleships. We can trace back indeed the genesis of the Alaska class to post-Washington treaty dicussions in all admiralties round the world. By definining the caliber 8-inches for “heavy cruisers”, assorted with a displacement limited (and the 6-in caliber) for light cruisers, the treaty defined a new standard which -as some admiralties believed- could alleviate the lack of battleships for some operation outside the traditional frame of cruisers, inherited from frigates.

Thes new cruisers were based on a brand new standard initiated by the Royal Navy, which already looked a “cruiser killers”, the Hawkins class, first to have 7.5 in guns (which was rounded to 8-in later). They had been created to deal with German commerce raiders (those of Von Spee in particular) and be posted in far away overseas, but when completed they had no more purposed and were single-out for their oddity. Standard British cruisers were “light” in post-WWI definition, as any other cruiser in the world, with 6-in guns only.

USS Northampton, one of the early USN treaty heavy cruisers

Deprived of their precious battleships, the admiralties looked at these 10,000 tonnes new ships and wondered, how much 8-in guns we can cram into these ships ? Many believed that having eight or nine of them firing HE shells twice as fast as any battleship gun could just outperform -added to superior speed to choose the engagement timing- any capital ship. The threat of battlecruiser in 1922 was now a remote chance. They had been banned and only the British retained three of these. Thus, the heavy cruiser became the new thing for these early interwar navies, a new territory to explore. And indeed, the light cruiser standard was soon sidelined and all navies started to crank out heavy cruisers as if there was no tomorrow.

Soon, the trend was “more gun, more speed” at the detriment of the armour. The logic is speed and the capacity to outrange any adversary whatever his ships might be was a deciding factor.

For example, the Hawkins 7.5 in guns (191 mm) reached 14,200 yards (13,000 m). Not bad consideing battleship guns of the 12-in caliber BL 12-inch Mk VIII gun (obsolete by then) reached 10,000 yds effective. But sure, BL 15-inch Mark I were able to reach 33,000 yards.

The first US heavy cruisers however, the Pensacola class, tried to pack a punch for a small tonnage, below 8,000 tonnes if possible. Their ten 8-inch/55-caliber gun were an amazing attempt to do more cruisers on the allocated global tonnage, with more guns -ten- than anything afloat at the time. And these guns reached a target at 30,050 yards (27,480 m), so almost the same as any battleship.

Thus, some already expressed the fear that if an enemy navy used such cruisers, they had to answer in nature (same type) or find a ship providing a competitive advantage, a “cruiser killer”.

The Deutschland class “pocket battleships”

The game changer in 1929 was the launch in Germany of the Deutschland-class “pocket battleships”. They completely rewrote the rules. Based on 10,000 tonnes, they brought a kind of artillery that can surclass any heavy cruiser, while retaining a speed advantage over any capital ship of the time.

The U.S. Navy therefore sought to counter these, fearing that might start a new arms race (which happened with the French Dunkerque class) and made heavy cruisers already obsolete if this became a new trend. Planning for ships able to counter these in a more concrete way emerged in 1936 after the deployment of the Scharnhorst-class.

The new unseen Japanese threat

This was compounded in 1936 as Japan retired from all treaties, and became super-secretive about its naval plans. Rumors grew that Japan was building its own new large cruiser class, the B-64 class, precisely as “cruiser-killers” capable of seeking out and destroying post-treaty heavy cruisers and between limited armor protection (vs. 12-in shells only) to preserve a speed of 31–33 knots and their 12-in artilley. However, as shown in the WW2 IJN cruiser lineage, this fear was based on partly bogus intel.

The Japanese already in 1918 with Hiraga’s “Design X” were Large Cruisers which were caracterized by four single shielded 305mm/45 (12 in) Type 37 Cannons, never approved.

However in 1937 came the first serious incentive to get he new USN “large cruisers” design going. The so-called “Chichibu Kadekuru” hypothetical Large Cruiser class designed as “heavy armored cruisers” according to US documentation of the time, with four planned, rated as 12-15.000 tons, 30 knots, six 12-in guns (probably 2×3 or 3×2). In a memo they were suspected to be “Japanese Deutschlands”, cheating on treaties. However of course this class emerged from combined erroneous informations between interpretation of what the Japanese said after 1936, misinformation or simply False information fabricated to convince the congress to vote for new warships.

But this was enough to motivate wargames and extrapolations which only fed the cause of larger heavy cruisers. In a strange twist of fate, this program was soon learned by the Japane, which in answer imediately started a “real programm”, the B-65 class. A Japanese “fake” which turned real, forcing to upgrade the B64 had the Soviet Navy start to plan the Stalingrad class

Author’s reconstruction of the B64

The B64 “cruiser killer” had a moderately size artillery while displacing 32,000/34,800 tonnes based on 802ft 6in oa x 89ft 3in wide hull, 160,000 shp for 33 knots, with 7.5-in armour immune against heavy cruiser’s shells at a time the Japanese ignored the Alaska class completely. The most interesting aspect was their triple 12.2 in guns battery in three triple turrets. They were dubbed much later “midget Yamatos”. These were a real project, moderately documented, and aimed at US treaty cruisers and post-treaty cruisers (so after September 1939). The Baltimore class were of course considered.

Design of the B-64 started in 1939 whereas test were carried out with the new long rangee 12.2-in (310 mm) guns. The design was completed in 1941.

However when the USS Alaska construction was revealed, and specs confirmed, the armament was changed by the IJN admiralty to 14.2-in (360 mm) guns in a 3×2 configuration, and approved in 1942. Eventually by that time, the IJN had other prorities, and none was laid down. The upgraded B65 were not much longer “cruisers” only based on their speed and armour. They could be seen as a new version of the Deustchland concept, based on a greater wartime tonnage. In the end however, they were considered in most publications as capital ships, no longer “cruisers”, leaving the Alaska class program unmoved in any way (see later).

Start of the design

The initial impetus in 1931 with the Deutschland class did not was followed by any action, but the 1937 Japanese “super cruisers” of the B-64 class, alleged to be more powerful than the current US heavy cruisers. It’s in 1938 that the General Board asked the Bureau of Construction and Repair (BuC&R) to conduct a “comprehensive study of all types of naval vessels for consideration for a new and expanded building program”. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the time was still very much interested in naval matters, more than previous presidents, and may have taken a lead role in further developments.

He notably allegedly wanted to counter IJN raiding abilities, which could in turn would enable the USN to answer German pocket battleships, existing and planned, as advanced by some authors. These were only informal discussion and they were never recorded, thus impossible to verify. Some authors also speculated this was “politically motivated” and not strategically planned, even encountering some opposition from the Admiralty. Roosevelt after all also put his personal weight in the conversion of Cleveland class hulls into “fast light carriers“, something also opposed by the Navy, and in particular admiral Ernest King, and still won his case based on authority alone.

Design of the class

A tortuous design process

The Alaska class faced numerous changes and modifications along the way in its layout in 1939, fed by the intervention of departments and individuals along the way. This explained why the design was also delayed. Before September 1939, treaties went into the way of such ships: They fit nowhere and were already beyond tonnage limits in all categories.

At least nine different layouts were discussed between C&R (later BuShips) and BuOrd:

The latter went from a 6,000-ton Atlanta-class AA cruiser (not shown here) to a variety of “overgrown” heavy cruisers with triple turrets, or even a 38,000-ton “super baltimore”:

Scheme S511-06 Heavy Cruiser Study: Preliminary design plan dated 18 January 1940: Largest size cruiser (Baltimore like) based on a 38,700 tons standard displacement. The main battery shows no less than twelve (4×3) 12″/50 guns, with a secondary battery of 8×2 5-in/38 guns, for 212,000 hp and 33.5 knots, and a hull 850 x 99/104.5 x 31.5 feet plus good Anti-torpedo side protection (four internal bulkheads) as shown in the section. Judged too ambitious. The final decision was to not go beyond 25,000 tonnes.

Scheme S511-07 Heavy Cruiser Study: “Proposed Heavy Cruiser – CA2-A”, 19 January 1940. Large cruiser proposal, 25,600 tons standard. Main battery: 3×3 12-in/50 guns, 6×2 5-in/38 guns, 150,000 horsepower for 33.5 knots. Hull 800 x 90 x 26.8 feet and good ASW side protection with four internal bulkheads as shown here in the hull section drawing. It had a rounded stern, generous aft section beam as for battleships and two aft catapults, one crane. Still in profile, this looked like a beefed up Baltimore.

Scheme S511-14 Heavy Cruiser Study: “Heavy Cruiser Study – Scheme 2” dated 19 March 1940. The smallest proposal studied based on 15,750 tons standard displacement. 4×3 8″/55 guns, 6×2 5″/38 guns, 120,000 hp, 700 x 72 x 23.5 ft hull.

Scheme S511-15 Heavy Cruiser Study: “Heavy Cruiser Study – Scheme 3” dated 20 March 1940. Baltimore-like heavy cruiser, based on 17,300 tons standard but with 3×2 12″/50 guns (plus 6×2 5″/38) for 120,000 hp and a 710 x 74 x 24.5 ft hull.

Scheme S511-16 Heavy Cruiser Study: “Heavy Cruiser Study – Scheme 4-A – “Convertible” dated 10 April 1940: A glorified Baltimore, reaching 17,500 tons standard with twelve 8″/55 guns (4×3) but convertible to 3×2 12″/50 guns twin turret mounted in the 1st, 2nd and 4th barbettes. She would have been seconded by twelve 5″/38 (6×2) guns based on 120,000 hp for 33.1 knots.Dimensions 710 x 74.5 x 24.7 feet. Scheme 4B was 6x 12-in/50 guns based on 17,850 tons, 25 feet draft, 33 knots.

Scheme S511-17 Heavy Cruiser Study: “12-Inch Gun Cruiser Study, CA2F” with hull sections for Schemes. The closest to the final design. Note in particular the “cruiser style” superstructures and bridge in particular. Later she went to a battleship style tower-structure instead.

Preliminary design plan prepared for the General Board dated 19 June 1940 for a ship displacing 24,700 tons standard, 28,300 tons trials with her main battery, seven 12″/50 guns (2×2 and 1×3 aft), twelve 5″/38 guns (plus light AA) for 150,000 hp and 33 knots. This was a 750 eet by 84 and 29 feet in beam and draught. The plan was 1:32 scale. Like for all these profiles, this was part of “Spring Styles Book” at the U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

The final General Board adopted a consensus view. In an attempt to keep the displacement under 25,000 tons, the ships were to have a limited underwater protection making them easy preys for Japanese torpedoes and or even shells in a plunging trajectory, even large shell’s close hits.

The final design agreed on was a “scaled-up Baltimore” with the same machinery as the Essex-class aircraft carriers, meaning a greater beam, in order to retain 33 knots. The consensus also fell on nine 12-inch guns in three triple turrets and standard belt and deck protection against 10-inch gunfire.

The Alaskas passed the critical stage as being budgeted in September 1940. They were however part of a much larger order called the Two-Ocean Navy Act in the most significant USN extension of its history. However the Essex-class being ordered at the same time (in large numbers) meant that from their primary surface-to-surface role, carrier group protectoion was added in her primary roles, a capability favored by Admiral King, which as said before, did not liked the Alaska’s concept overall. It was a concession whuch did not hampered mich the ship’s overall capabilities. In that escort role, their large hull had as side effect far more stability, making them far more valuable base for AA upgrade and additions than heavy cruisers. At the same time, they were the “insurance card” against reported Japanese super cruisers in case. Some also saw these ships kept for escort a way to free up cruisers for their intended role of scouting and preying on enemy communications lines.

Hull and general design

Final design, as published in ONI

The final hull displaced 29,771 long tons (30,249 t) standard and 34,253 long tons (34,803 t) full load, so way more than the intended 25,000 tonnes standard. It was a compromise between the designs shown above. The hull seen from above, was less shaped like a battleship (pear style), narrow forward for very fine entries, and bulkier aft. It was not shaped as a larger Baltimore-class ship either, with a transom stern. Instead, it was a compromise between the two, with a bulkier aft section, fine entries but still narrow-waist and with a near-transom rounded stern.

Design of the after deck house, NARA

She had a flush-deck hull also, with a prow gradually raised to the point it towered twice as high compared to the stern, for good sea keeping. The final version even included a bulwark.

The hull was 791 ft 6 in (241.25 m) long at the waterline and 808 ft 6 in (246.43 m) overall for a beam of 91 ft 9.375 in (28.0 m) at the largest section aft, and a draft rabging from 27 ft 1 in (8.26 m) mean up to 31 ft 9.25 in (9.68 m) when fully loaded.

USS Missouri and Alaska in Norfolk 1944, helping to appreciate the different in hull shape.

Armour protection layout

Main Protection:

The main armor scheme was a compromise from several early design studies. The base line was the full protection offered against any 8 inch shells at any range. She had her 12 inch guns to essentially out-range any of these cruisers.

–Armor Belt 9 inches thick, tapered down at the bottom to 5 inches (228.6-127mm) with an inclination downwards to 10°, and external. It covered more of the waterline than a conventional cruiser.

–Deck armor varied by three layers between 3.8 to 4 in (97–102 mm) instead of the 1-3 inches thick (16mm to 76mm) initially planned, the thickest being the bottom of the citadel under the waterline.

–Weather (main) deck: 1.4 in (36 mm)

–Splinter (third) deck: 0.625 in (15.9 mm)

–conning tower was armored with 10.6 inches sides (269 mm) walls, with a 5 inches (127mm) roof.

–Turrets: 12.8 in (330 mm) face, 5 in (130 mm) roof, 5.25–6 in (133–152 mm) side and 5.25 in (133 mm) rear.

–Barbettes: 11–13 in (280–330 mm)

ASW Protection:

This was the “poor child” of the design. Still, the underwater protection was designed to resist a 700 lb TNT torpedo warhead with variations of early designs showing a 500lb charge as minimum to narrow the waist and reduce weight, unknowingly of the Type-93 “Long Lance” Torpedo (which boasted a 480 kg (1,100lb) warhead…

The torpedo itself was found and examined in 1943 and of the Alaska’s underwater defense was better than any due to better longitudinal stiffening due to a longer main armor it was well below Battleship standards of the time. Still, she was provided a double bottom instead of the planned triple bottom.

However the double bottom design was reinforced by the ammunition magazines to make for a stronger double bottom design, and without increased weight or strength compared to a triple bottom design, a clever compromise.

Powerplant

Alaska’s auxiliary diesels

The Alaska combined four propeller shafts driven by General Electric steam turbines each, double stage and with double-reduction gearing, fed in turn by eight Babcock & Wilcox boilers.

The Alaska Class used very high pressure (up to 634 psi) boilers, had for the first time reliable double-reduction gears for her steam turbines helping improving efficiency, reducing total weight for the same targeted speed. By 1936, the boiler standard was 600 psi at 850° F and a large pressure enabled speeding up the turbines more for a total output of 180,000 horsepower versus 150,000 horsepower for a lower pressure machinery of the same size and weight.

There was a catch however, as these extreme pressured had not been tested throughly yet so these figures were something to kept relatively expecptional, or not abuse for it to cause any damage for an extended length of time. Thanks to this output, a top speed of 31 kts could be obtained for long periods, helped in part by a favourable hull ratio of 8.8. (The average cruiser was 10, the average battleship 6). This final powerplant enabled an normal top speed of 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph).

But when overloading the turbines, the ship was even able to maintain runs of 35 kts for a short run. Still, some in the Navy complained that she could have been equipped with the same machinery as a battleship, and retired from it an even greater output (such as 200,000 horsepower) and a speed estimated to 36-37 knots as a result, on par with a Scharnhorst or the estimated speed of a B-64/65.

USS Alaska in a tight turn, 1944. The class was not very agile, having a very large turning cicle and bleeding speed fast.

This would havd allowed an Alaska to prey on cruisers as intended, and chase down nearly any other ship while enabling to flee even the latest generation of fast battleships. However at the time her machinery was first designed, she was to be used against ships believed to be slower than her, so the additional machinery weight and additional cost was not considered justified, especially if that was going to need any more sacrifice in protection, already compromised.

Armament

Main: Three triple 12-in/50 guns

USS Guam in a firing exercize

As built, the Alaska class had nine 12-inches/50 caliber Mark 8 guns.

They were mounted in three triple turrets, two turrets forward and one aft. The “2-A-1” configuration was classic, used by US heavy cruisers as well as modern battleships.

The latest 12-in guns manufactured for the U.S. Navy of the Mark 7 were intended for the Wyoming-class (1912) and gun technology went quite a long way since.

The Mark 8 was still based on the Mark 7, but of far better quality and refinement as well as with a longer caliber. As stated by the ordnance, it was “by far the most powerful weapon of its caliber ever placed in service”. Design process started in 1939. The final ordnance piece weighted 121,856 pounds (55,273 kg), barrel and breech. It was tested and shown able to sustain 2.4 to 3 rounds a minute on average, versus one on the Mark 7.

Its tailored shells weighted 1,140-pound (520 kg) each. The Mark 18 armor-piercing (AP) was able to cross 38,573 yards (35,271 m) range when fired from an elevation of 45° (which was far better than the Wyoming’s Mark 7). Each of these had a calculated 344-shot barrel life, more than the 16″/50 Mark 7 of the Iowa class. This made the Alaska indeed, the best armed cruisers of World War II, estimated equal or superior to the venerable battleship standard 14″/45, thus they would have been also a nightmare for any IJN capital ship in case.

The turrets simply retook the Iowa-class design, but smaller of course and adapted in several ways:

-Two-stage powder hoist (1-stage on Iowa), making them safer and faster.

-Projectile rammer transferring shells from storage to the “barillet” feeding the guns. (Later this proved unsatisfactory, and not installed onr Hawaii)

Only ten turrets were manufacture, with one spare at $1,550,000 apiece. They ended as the most expensive gun/turret combo ever purchased.

Secondary

USS Alaska’s secondary battery in fire drill

The secondary battery of the Alaska class comprised twelve dual-purpose (anti-air and anti-ship) 5-in/38 (six twin mounts, four on the superstructure sides, two centerline fore and aft as in all designs but the first). This ensured better arc of fire overall, although some argued that she could have crammed three per side with some design revision. Given the performances of these, this was still good enough completed by an extensive AA, more than any other cuiser in US inventory. Full history and specs.

AA

Famous photos of the time showing the crew of a 40 mm/56 battery in drills.

The light anti-aircraft armament as planned was fifty-six (56) barrels of 40 mm Bofors guns, spread on the decks through fourteen quad mounts. Full specs

For close-in air defence (the smaller bubble), thirty four (34) 20 mm single barrels Oerlikon guns were provided, placed in various positions across the decks. As a reminder, a Baltimore boasted 48×40 mm and 24×20 mm and 60×40 mm/36×20 mm on a North Carolina in 1945. Full specs of the 20mm Oerlikon

Air Park

Curtiss SC Seahawk being recovered by USS Alaska after climbing on the landing mat, awaiting pickup by the ship’s crane. This model was piloted by Lieutenant Jess R. Faulconer, Jr., USNR. 6 March 1945 (cc)

As planned for completion in 1943, the first two would have been equipped with four Vought OS2U Kingfisher, and the third by the more modern Curtiss SC Seahawk. However photos shows generally the latter. Nothing was planned for USS Hawaii.

Curtiss SC from USS Alaska, March 1945 (from the photo above), author’s profile

Close view of the catapults, USS Alaska

Liveries

MS32/7C design scheme for USS Alaska.

USS Alaska in Measure 32, design 7c

USS Alaska in Measure 22, 1945

USS Guam as completed in measured 32/7c. All: From shipbucket, author Ian B. Roberts, wikimedia under CC licence.

Construction & Fate

Construction

Launch of USS Alaska

The Alaska class was to have six ships laid down originally. But when it became apparent that the concepts behind appeared already obsolete, the next three scheduled to be laid down by June 1943 were canceled. The two completed in wartime, USS Guam and Alaska, were launched in 1943, and USS Hawaii in March 1945, and where the first two were completed in June and September 1944, the last wasnot. One reason fpor the delays before and during construction was a sudden and dramatic shortage of steel. Already anticipated for smaller ships, misc. vessels started to be built in wood, and like in WWI, concrete made its return for many projects (or vital ships for the USN morale like the ice cream barge).

USS Alaska was ordered as CB-1, at New York Shipbuilding Corporation, Camden, on 9 September 1940. She was laid down on 17 December 1941, launched 15 August 1943 and completed on 17 June 1944, so almost four years. She was place in reserve as soon as 17 February 1947 and mothballed until sold for BU at Newark in 1961.

USS Guam (CB-2), named after the island and territory, soon to be under Japanese occupation, was laid down on 2 February 1942, launched on 12 November 1943 and completed on 17 September 1944. She had the same fate as her sister and ended BU at Baltimore in 1961.

USS Hawaii (CB-3) was delayed and laid down on 20 December 1943, CBC-1 on 3 November 1945 when launched, mothballed without completion but many projects. Eventually discarded and sold for BU at Baltimore, 1960.

USS Philippines (Commonwealth of the Philippines) as CB-4 was to be laid down when cancelled by June 1943.

USS Puerto Rico as CB-5 went through the same fate.

USS Samoa (American Samoa) as CB-6 suffered the same fate.

Evaluation

They proved in operation that they were a difficult concept to deal with, leacking their intended adversary, reduced to fire support duties and AA escort (something any other ship can do) while being very expensive in maintenance, crew, and in the 1950s eventually outclassed by missiles. These dinosaurs had no place in the fleet and they were placed in reserve in 1947 already.

About their “recycling”

In 1958, the Bureau of Ships prepared two feasibility studies for a guided-missile cruisers conversion one, with removalof all armament and fitting of four different missile systems, jusged way too costly at $160 million, followed a halving this conversion, to the aft part, at $82 million, still overpriced in a context of budget cutting. They were sold for scrap after being stricken in 1960, but the near complete USS Hawaii was also considered for a conversion very early. She would have been in fact the first USN guided-missile cruiser, and this would have lasted until 26 February 1952 before being cancelled. He conversion to a “large command ship” followed (CBC-1) like Northampton, but on 9 October 1954 she was back at CB-3 and eventually stricken on 9 June 1958 sold for BU one year before her sisters (more detail later). It should be mentioned that the admiralty as early as 1942 explored the possibility of converting the ships while very early in construction, into aircraft carriers. The sad fate of these ships, seeing only a couple years of active service, is to be placed at the same level of the many massive spending for little results in the end for the taxpayer’s money. Like Howard Hugues’s “spruce goose” which was to replace liberty ships, or the dramatically mediocre and complete industrial disaster that was Brewster.

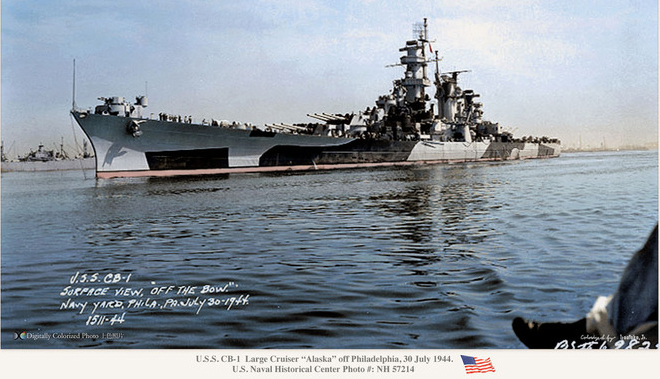

USS Alaska in july 1944

⚙ Alaska specifications as built |

|

| Displacement | 29,780 t. standard -34 253 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 808 ft 6 in oa x 91 ft 9.375 in x 31 ft 9.25 in mean (246.43 x 27.76 x 9.70 m) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts GE turbines, 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 150,000 hp |

| Top Speed | 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) |

| Range | 12,000 nautical miles (22,000 km; 14,000 mi) at 15 knots |

| Armament | 3×3 12-in, 3×2 5-in/38 DP, 14×4 40mm, 34x 20 mm AA, see notes |

| Protection | Belt 220, turrets 315, bridges 80-100, blockhouse 270 mm |

| Crew | 1,417 |

USS Alaska off Philly NyD, 30 July 1944

USS Alaska being completed by June 1944, commissioned on 17 June under command of Captain Peter K. Fischler steamed down to Hampton Roads escorted by destroyers USS Simpson and Broome to be deployed for her shakedown cruise in the Chesapeake Bay and Caribbean, notably off Trinidad, escorted by USS Bainbridge and Decatur. She returned to Philadelphia Navy Yard for post-shakedown fixes and alterationsn receivig notably four Mk 57 fire control directors for her secondary battery. On 12 November 1944 she left Philadelphia with USS Thomas E. Fraser for two weeks of extra trials off Guantánamo Bay in Cuba, and left on 2 December, for the Pacific via the Panama Canal, arriving in San Diego on the 12th. Gun crews started a training in shore bombardment and AA screening accoridng to her future tasks.

On 8 January 1945, USS Alaska left California for Pearl Harbor (13 January), participating in more training, assigned to Task Group 12.2 bound for Ulithi, on 29 January, arriving on 6 February and merged into Task Group 58.5 (TF 58 – Fast Carrier Task Force). TG 58.5 was assigned to the screen, and USS Alaska in particular was assigned to the veteran carriers USS Enterprise and Saratoga. They head for Japan on 10 February for air strikes against Tokyo and its area, in impunity, and USS Alaska was transferred to TG 58.4, supporting the assault on Iwo Jima. She screened the carriers for 19 days and was back to Ulithi fore resupply and rest.

USS Alaska in the Atlantic, 1944

USS Alaska was back with TG 58.4 for the campaign of Okinawa, assigned to screening USS Yorktown and Intrepid leaving Ulithi on 14 March bound for an area southeast of Kyushu for the first air strikes with USS Alaska having her first battle: The Japanese launched a massive Kamikaze attack and her anti-aircraft gunners claimed a Yokosuka P1Y bomber trying to hit USS Intrepid. It’s her radars that launched the alert of another impending attack and ten minutes later, her gunners spotted and shot at by error a lone Grumman F6F Hellcat fighter, the pilot was uninjured. Later she downed a Yokosuka D4Y “Judy”.

When USS Franklin was badly damaged by bomb hits and a kamikaze, USS Alaska and USS Guam, now in the same unit, as well as two other cruisers and destroyers were detached, forming 58.2.9 in order to escort the crippled Franklin to Ulithi. They were attacked and USS Alaska claimed another D4Y. It happened that gunfire from one of her 5-inch guns accidentally caused flash burns on several men nearby which became her only casualties of war. She became fighter director due to her better air search radar, vectoring fighters in interception along the way, and downed a Kawasaki Ki-45 Toryu. On 22 March at last TG 58.2.9 arrived in Ulithi, Alaska departing immediately to return to TG 58.4.

She went on screening aircraft carriers off Okinawa but on 27 March, was detached for the bombardment of Minamidaitō, soon joined by Guam and two light cruisers and escorted by DesRon 47. The night of 27–28 March she landed 55 12-inch shells, 352 5-inch on target. After refuelling they were back to Okinawa to support the landings from 1 April. On the 11th, there was another air raid and she downed one Japanese plane, assisted a second and claimed what was possibly a rare Ohka “Baka” piloted rocket-bomb. On 16 April she claimed three, assisted with three. The routine went on and she was never hit.

USS Alaska under air attack in 1945

USS Alaska returned to Ulithi for a resplenishment, she arrived on 14 May, still assigned to the same group, which just changed name for TG 38.4. She was soon back to Okinawa to resume her anti-aircraft defense role and by 9 June she was detached with Guam to bombard Oki Daitō. She was sent to San Pedro Bay (Leyte Gulf) for rest and maintenance, until 13 July, then reassigned to Cruiser Task Force 95 (Rear Admiral Francis S. Low.). On 16 July, Alaska and Guam made a sweep into the East China, Yellow Seas, sinking any Japanese shipping on sight. On 23 July they joined a major raid into the estuary of the Yangtze River, off Shanghai. She learned about the Japanese surrender on 15 August.

Guam and Alaska at anchor off the coast of China, 1945

On the 30th, Alaska left Okinawa for Japan, with the 7th Fleet occupation force, and moved to Incheon (Korea) on 8 September to support operations until 26 September, headed for Tsingtao to support the 6th Marine Division, until 13 November and bacl to Incheon for her first take on Operation Magic Carpet, with troops aboard, just demobilized. She left for San Francisco, and from there, after resplenishment, corssed Panama for the Atlantic on 13 December, arrived in Boston Navy Yard (18 December) for reserve preparations. She left on 1 February 1946 for Bayonne in New Jersey, to be berthed in reserve. On 13 August, she was placed in reserve, still able to be refitted for service, and was not decommissioned until 17 February 1947. For her WW2 service she was awarded three battle stars.

In 1958, BuShips made two feasibility studies by demand of the board to see if the large cruisers were suitable for a conversion as large guided missile cruisers. The guns turrets were to be removed and four different missile systems installed, but at a cost of $160 million this was denied and the second sty left the forward battery intact and missiles installed aft, now down at $82 million, but it was shelved again. The large ships were too costly to operate and of little use at that stage, and Alaska was stricken for good on 1 June 1960, sold on the 30th and BU by Lipsett Division, Luria Brothers.

USS Guam in shakedown off Trinidad, 13 November 1945

USS Guam was was completed by September, commissioned on the 17th under command of Captain Leland Lovette. She left Philadelphia on 17 January 1945, after her shakedown cruise in the Carribean, sailed through the Panama Canal and after a stp to San Diego, sailed to Pearl Harbor (8 February), being visited there was Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. On 3 March, she sailed to Ulithi, for her first deployment, joining her sister Alaska on 13 March. Under command of Admiral Arthur W. Radford, her group was tasked to raid the Kyushu and Shikoku as part of TF 58, arriving on 18 March. There, she soon faced her first kamikazes and bombers attacks, USS Guam being detached to escort USS Franklin back to Ulithi until 22 March.

At her return she was assigned to Cruiser Division 16 (CruDiv 16), part of TG 58.4 deployed off Okinawa. The night of 27–28 March, saw her shelling a Japanese airfield on Minamidaitō. She was back at screening carriers during the operations off Nansei Shoto, until 11 May. After resplenishment at Ulithi she was back off Okinawa with TG 38.4, part of reaorganized TF 38 (Halsey’s 3rd Fleet). She screened carriers during the sweeps of Kyushu. USS Guam and Alaska were detached again for shelling airfields at Oki Daitō on 9 June. Her group was sent for a refit and long resplenishment and rest at San Pedro Bay, Leyte Gulf, from 13 June to mid-July.

USS Guam at Philly NYD, October 1944 and in the Delaware River in January 1945

Back to Okinawa where the campaign was mostly over, USS Guam was reassigned to TF 95 as flagship for Rear Admiral Francis S. Low with USS Alaska. This cruiser force was deployed on 16 July for a sweep into the East China and Yellow Seas, targeting shipping, but with meagre results. They did the same on the Yangtze river with a large force, with three battleships and three escort carriers, off Shanghai, but again, this was pretty uneventful. The force was back off Okinawa by 7 August.

USS Guam became flagship of the “North China Force” (RADM Low) tasked to show the flag in the region between Tsingtao, Port Arthur, and Dalian. On 8 September 1945, as the war ended, USS Guam entered Jinsen in Korea to provide cover for the occupation. She left Jinsen on 14 November for San Francisco with many demobilized Army soldiers, arriving on 3 December. On the 5th, she sailed out for Bayonne, New Jersey, demobilized, then decommissioned on 17 February 1947. Although part of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet, conversion projects went to nil and she was stricken on 1 June 1960, sold on 24 May 1961 to Boston Metals Co., Baltimore, towed there on 10 July 1961. She likely earned two battle stars for her service.

Launch of USS Hawaii on 3 November 1945, the war has ended for months by then and her fate was very uncertain

Like the Montana-class battleships and rest of the Alaska-class, USS Hawaii saw her construction suspended in May 1942. Materials and facilities were diverted for other more urgent constructions. Over 4,000 long tons of steel plates pre-assembled for Hawaii were reused from July 1942. USS Hawaii returned on the construction queue on 25 May 1943 but not CB-4, CB-5 and CB-6, cancelled for good on 24 June 1943. USS Hawaii’s keel was laid on 20 December 1943, she was launched on 3 November 1945, but completion work was halted in February-April 1947 due to a massive budget reduction, when she was 82.4% complete with her main battery turrets fitted, superstructure almost complete, to be removed as she entered the reserve fleet, Philadelphia NyD.

In construction, details of the bridge and stack area

From there, her “purgatory” commence. Built far too late based on a concept that was proven wrong (Her prewar concept of “cruiser killer” was now completely obsolete), apart for screening and shore bombardment like her sister, there was little esle to do for her. And there were many ships that can do the same more efficiently.

Thus, the admiralty board started a serie of plans to have her converted. Here is this story:

S-511-50 “Aircraft Carrier, Converted from 12″ Cruiser (Class CB 1-6)”

First Aircraft carrier conversion (1942): Preliminary design plan prepared for the General Board to explore possible carrier conversions of CB type cruiser hulls under construction.

The “Advance Print” plans were dated 3 January 1942, represents what could have been the conversion of USS Hawaii and folloinwg ships if cancelled mid-construction. This was eventually similar external appearance to the Essex (CV-9) class, but with lower freeboard, two aircraft elevators, one catapult, and a somewhat shorter 839 feet long flight deck offset to the port side. Aircraft capacity was also inferior, perhaps around 70 aircraft adn the design would have had reduced steaming endurance, modest ASW protection. But overall far more valuable than any of the CVLs. “Spring Styles Book”, Naval Historical Center, U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph.

Second conversion project (1948): Hawaii was the first considered under project SCB 26 conversion to an aircraft carrier, but on a modernized package. She owould have been fitted with an aircraft crane, two aircraft catapults on the stern and looked similar to a completed Graf Zeppelin-class in some ways. One of the particulars of her designs was to be able to launch the JB-2 “Loon” cruise missile, from a hydraulic catapult installed on her forward flight deck. The conversion was authorized in 1948, scheduled to be completed in 1950 under the designation of CBG-3. It was canceled in 1949 as all plans to equip ships with ballistic missiles based on the danger presented by the volatility of the rocket fuels and unreliable guidance systems at the time.

Guided-missile cruiser designs (1946-48)

Similar to the unfinished battleship Kentucky, USS Hawaii was to become a test platform for guided missiles development by September 1946. As CB(SW) she would have been rearmed with sixteen 3-inch (76 mm) L70 guns (8×2) for conventional close defence, and missiles mounted toward the bow, with in additional two “missile launching pits” (early ancestors of modern VLS) located near the stern. Armor was removed, but the plan was never carried out, probably based on cost concerns.

In 1948, project SCB 26A proposed her conversion to a Ballistic Guided Missile Ship. She would have been fitted with 12 vertical launchers based on the German V-2 (short-range ballistic missiles) and 6 launchers for the new SSM-N-2 Triton surface-to-surface cruise missile. The latter was more reliable as a cruise missile and the design process was approved by September 1946. Designers settled on a guided missile weighting 36,000-pound (16,000 kg) and ramjet-powered paired with solid-fuel rocket boosters to reach 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 km) at Mach 1.6–2.5, in 1950. The final version was awaited by 1965, but between the SSM-N-9/RGM-15 Regulus II and UGM-27 Polaris submarine-launched cruise missile coming, the project was terminated in 1957. The design was also modified to fire the XPM (Experimental Prototype Missile) instead of the Triton, until cancelled for the RIM-8 Talos.

Large command ship (1951)

SCB 83 was another attempt to complete the hull with a valuable addition to the USN: The project started in August 1951 was similar to the USS Northampton on a larger scale, with more expansive flag facilities, fully capable radar and communication systems to be an organic part of a carrier task force. No facility for amphibious operations was procured and armament comprised an impressive array of …sixteen 5″/54 caliber guns in single mounts. Her superstructures would have been tailored to support the AN/SPS-2 on top of a forward towerand AN/SPS-8 on the aft superstructure and a lighter SC-2 mounted on top of a short tower, aft of the stack to “tropospheric scatter communications”.

USS Hawaii could also have carried two Mk37/25 fire-control directors fore and aft of the superstructure for her main guns. Conversion was eventually authorized as CBC-1 on 26 February 1952 and it was even integrated in the 1952 budget. The hull saw the removal of her 12″ turrets and delays were imposed to enable extra experience from USS Northampton to be analyzed before the conversion design was even finalized. Some in the admiralty believed a light carrier such as USS Wright -Saipan class) could have reached the same objective at a much smaller cost overall, and the conversion was cancelled in 1953.

Polaris launching ship

In February 1957 the project “Polaris Study–CB-3” was published, and she would have been modified to house and operate twenty Polaris missiles mounted in silos where the third main turret would have been. It was completed by two Talos surface-to-air missile launchers fore and aft with reloads, two Tartar SAMs on either side of the superstructure and an ASROC ASWR in place of the second main turret. But it stayed at paper stage.

On 9 June 1958 at last, USS Hawaii was struck from the Register and she was sold to Boston Metals, Baltimore, on 15 April 1959; towed there on 6 January 1960 and broken up.

USS Hawaii being towed away for scrapping, 20 June 1959

“Large Cruisers”, the debate on Alaska’s categorization

The US Navy designation was ‘large cruiser’ (CB) -there is no signification in the second letter- and most leading reference works consider them as such, or more colloquially “cruiser killers”. Various other works alternately described these as neo-battlecruisers, despite the US Navy officially never classified them as such. The Alaskas were named after outer territories or insular areas of the United States, a reflection of their intermediate status, between larger battleships and heavy cruisers. They really were isolated in their own branch.

The Baltimore rose to 17,000 tons at full load, whereas Prinz Eugen reached 20,000 tons. However their main armament still remained eight or nine 8-in (203 mm) cannons. With the Alaska, went for the 12-in or 305 mm caliber, a call nack to early pre-dreadnoughts. Their distribution and the general outlook brought them much closer to contemporary battleships, hence the term “battle cruisers” sometimes put forward. This take into account their speed of 33 knots and relatively light armor. But in that case what are the Iowa class ? What would have been the Montanas ?

So the Alaska class, along with the Dutch Design 1047 battlecruisers, Japanese Design B-65 were the only known fully realized “heavy cruisers killers” ever built, described alternatively in the litterature “super cruisers”, “large cruisers” or even “unrestricted cruisers” (from treaties).

The case for “battlecruisers” was never never official and a bit lazy as designation, reserved for true capital ships, which were not. Early in its development, however the designation “CC” used for the Lexington class was given, casting doubt.

USS Alaska in manoeuvers in front of USS Missouri, 1944

However, this designation was changed to “CB” of “large cruiser” (created for her) and all the teams and personal involved at design stage were discouraged to use the term “battlecruiser” at any level. The U.S. Navy named the ship as overseas U.S. territories rather than states or cities to symbolize this intermediate status further.

The Alaska class with their final superstrcture though looked more toward US battleships in appearance and their displacement was indeed twice that of a Baltimore class, just 5,000 tons shy of the Washington Treaty’s battleship standard displacement limit (35,000 long tons). They were even longer than a King George V class or North Carolina class.

The final package made them proof against German “pocket battleships” (11-in shells) both Deutschland and Scharnhorst-class but they were plagued by an inadequate underwater protection, even inferior to the French Dunkerque or German Scharnhorst. They needed a close destroyer escort at all time, which was fine if they stayed in the same task force, but defeated their use as a “cruiser hunter”, or by taking chances at full speed.

As for providing an adequate AA protection to the task force, their secondary battery was lacking compared to their displacement, twice as much as a Baltimore class. They had the same 5-in/38 gun battery, albeir compansatd by a better light AA and a margin to add more. Part of this was explained by their adoption of broadside aircraft catapult like older US cruisers and unlike battleships, sacrificing a lage portion of the superstructure. They would have been better off with rear catapults, enabling a shoehorn an extra pair of 5-in/38 turrets.

They also possessed aircraft hangars and single large rudder, so less redundancy than a battleship, and combined to their great length made for a turning radius of 800 yd (730 m) exceeding even larger battleships and carriers, and making them quite unwieldy, beeding precious speed in excess for any manoeuver and defeating the purpose of chasing down cruisers in the first place. Author Richard Worth summed up this by declaring that their had the “size of a battleship but the capabilities of a cruiser”. Yet they proved as expensive to build and maintain as any battleship, which combined by overall lesser capabilities and armor deficiencies with no advantage in speed compared to the Iowa class, did not favored their case long-term.

And still, many publications of the time, out of official reach, went on calling her a battlecruiser. Official navy magazine All Hands for example in its article describe “The Guam and her sister ship Alaska are the first American battle cruisers ever to be completed as such.” Author Chris Knupp noted that these ships not only retook the same recipes, but “fulfilled the battlecruiser role by creating a larger, more powerful heavy cruiser whose design already offered less armor and higher speed, but by enlarging the ship they gained the heavier firepower”. Their armour-displacement ratio was indeed 28.4%, and it was even inferior to a ship built as such, like HMS Hood (32%) and only the Lexington-class had the same 28.5%. Armament-wise she was weak if compared to WWI standards, but on paper as her lighter guns had performances way above and beyond those of the “classic battlecruisers” still in service in WW2. So again, pleading her cause as battlecruiser.

Read More

CQM takes sextan reading on USS Alaska, 1945

Books

“Alaska III (CB-1)”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 11 June 2015.

Cressman, Robert (2000). The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. NIP

Egan, Robert S. (March 1971). “The US Navy’s Battlecruisers”. Warship International. International Naval Research Organization. VIII

Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946.

Friedman, Norman (1984). U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. NIP.

Garzke, William H. Jr.; Dulin, Robert O. Jr (1976). Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II. NIP

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. NIP

Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers, 1905–1970. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Dulin, Robert O., Jr.; Garzke, William H., Jr. (1976). Battleships: United States Battleships in World War II. NIP

“Hawaii”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command.

Parsch, Andreas (2003). “SSM-N-2”. designation-systems.net.

Scarpaci, Wayne (April 2008). Iowa Class Battleships and Alaska Class Large Cruisers Conversion Projects 1942–1964. Nimble Books LLC.

“USS Hawaii (CB-3); 1940 program – never completed”. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command.

Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. NIP.

Links

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:USS_Alaska_(CB-1)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alaska-class_cruiser

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:USS_Hawaii_(CB-3)

ibiblio.org/hyperwar/ Various designs and biblio about the Alaska

The Modern Cruiser: The Evolution of the Ships that Fought the Second World War By Robert C. Stern