Author: naval encyclopedia

Sierra class submarine

Project 945 Barrakuda (NATO SIERRA I) Project 945A Kondor (NATO SIERRA II) Nuclear attack submarines: 5 planned, 4 completed 1979-1992,…

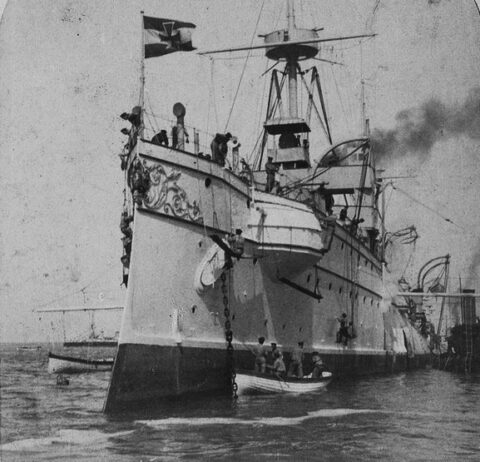

Update Etna class cruiser

Etna was the only survivor of a class of four protected cruisers dating from 1885-1888. Designed by Carlo Vigna and…

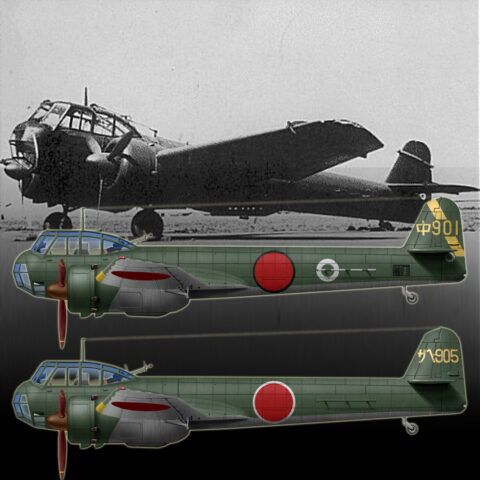

Kyūshū Q1W Tōkai “Lorna”

IJN ASW aircraft (1943-1945) 153 built The Kyūshū Q1W Tōkai (“Eastern Sea”) was the first and last Imperial Japanese Navy…

Hunt class Destroyer Escort (Type 1)

UK Royal Navy: 23 (86 total) ships. The Hunt class were escort destroyer of the Royal Navy, with first vessels…

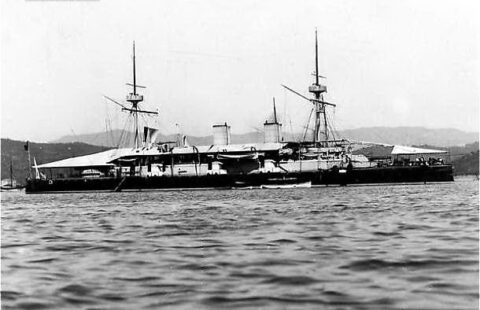

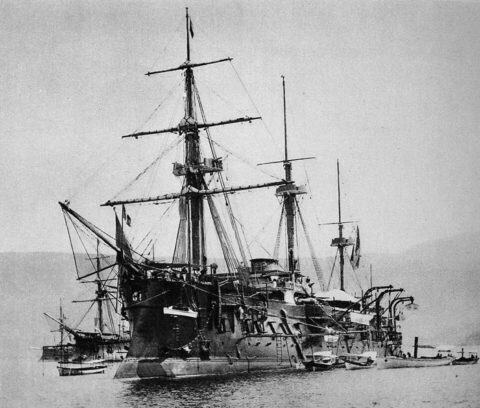

Colbert class Ironclad (1875)

France. Central Battery Ironclad Colbert, Trident Built 1870-78, service until 1900 The Colbert class were a pair armored frigates and…

Iris class cruiser (1877)

RN (1875-79, service until 1905-19): Iris, Mercury The Iris class Cruiser were an important milestone in the development of the…

Zumwalt class destroyer

Guided Missile Destroyer (2011-2027): DDG-1000 Zumwalt, DDG-1001 Michael Monsoor, DDG-1002 Lyndon B. Johnson For this 4th of July here is…

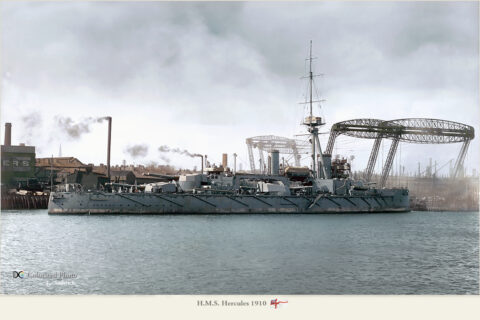

Update ! Colossus Class

The Colossus-class battleships were 1st generation dreadnought battleships of the Royal Navy built at Palmers and Scott shipyard in 1909-1911….

U23 class (1912)

Germany: SM U23, 24, 25, 25 (1912) The U23 class submarine were of the so-called double-hulled type, designed as oceanic…

dbodesign

dbodesign