Category: Uncategorized

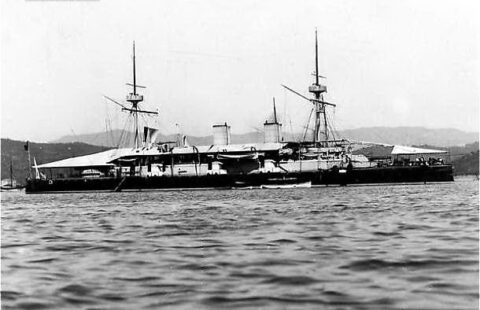

Update Etna class cruiser

Etna was the only survivor of a class of four protected cruisers dating from 1885-1888. Designed by Carlo Vigna and…

The Atlantic Wall

The Atlantic Wall was a massive system of coastal fortifications built by Germany during World War II, along the western…

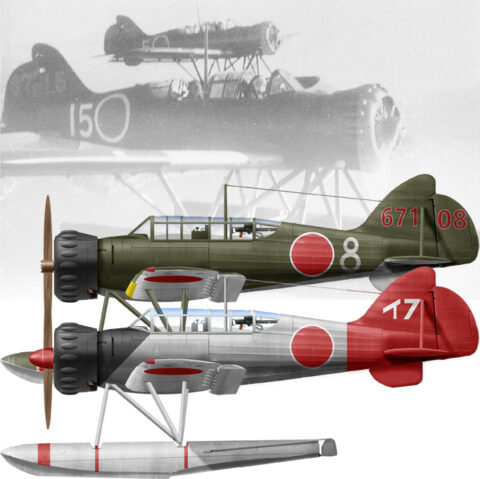

Yokosuka (Kugisho) E14Y (1941)

Submarine-launched seaplane, 123 built 1939-43. Development Origins The Yokosuka Type 0 Small Reconnaissance Seaplane (in Ordnance E14Y, Allied Intel “Glen”)…

Cincinnati class Cruiser (1892)

USA (1887-90): Protected Cruiser C-7 Cininnatti C-8 Raleigh 1892-1921 The Cincinnati-class were two small protected cruisers built for the USN…

Type 094 Jin class SSBN (2004)

Chinese PLAN (2001-2021): Changzheng 11-21 The Type 094 (or 09-IV, NATO reporting name Jin class) are the current generation of…

Belgrano class cruisers (1951)

Argentinian light cruisers: ARA 9 de Julio ex-Boise, ARA Belgrano ex-17 de Octubre, ex-USS Phoenix 1951-1982. Belgrano before 1982, photo…

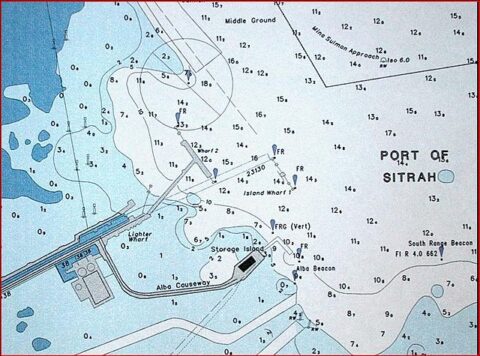

Hydrography

Hydrographie : L’hydrographie est la branche des sciences appliquées qui traite de la mesure et de la description des caractéristiques…

Pirates !

🏴☠️ Embarquez pour un voyage au cœur de l’âge d’or de la piraterie ! Explorez l’univers fascinant des pirates :…

Halloween Special ! Ugliest Ship ever

The POLL is closed Results: -HMS Victoria (1887) (1) -french hotel warships (1)* -The round ship (1) -USS Choctaw (2)…

dbodesign

dbodesign