Duncan class Battleships (1901)

HMS Albemarle, Cornwallis, Duncan, Exmouth, Montagu, Russel

The last gasp of the “Russian scare”

The “Peresvet killers”

The six Duncan class were pre-dreadnought battleships ordered in response to Russian naval shipbuilding, notably the Peresvet class. They were there to hunt the hunters, as these Russian battleships were designed to go after the 2nd class Centurion class battleships on one hand, and the older Powerful class armoured cruisers designed to hnt down the far east cruisers Rurik, Russia and Gromoboi that started it all.

On the larger picture and design-wise, the six Duncan class pre-dreadnoughts registers at the same time between the London class, wich cemented the British Battleship standard design for the years to come, and the King Edward VII and Lord Nelson class, which sere already semi-dreadnoughts. They were thus, the very last “classic” British pre-dreadnoughts. So the design basis was still the London class, unlike the previous Centurion class (Centurion, Barfleur, Renown) and thus, largely updated after almost ten years of technological advances.

Design changes

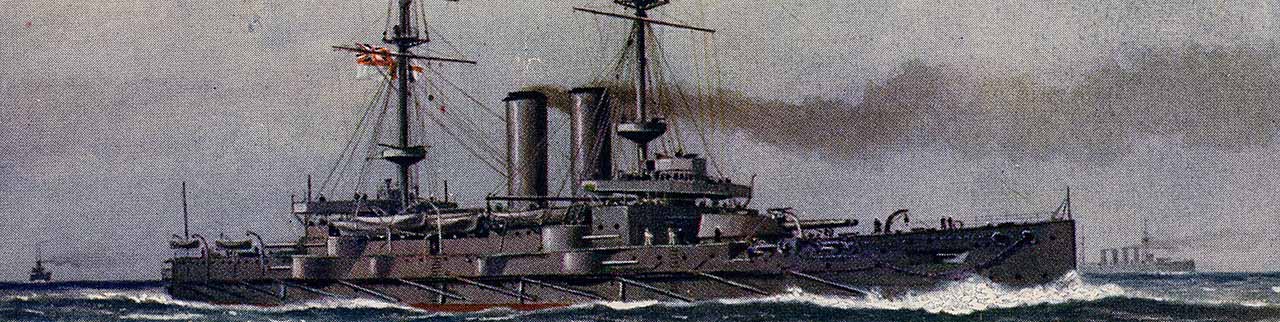

HMS Russel just completed with her peacetime livery.

Overall, the Duncan class battleships were completely tailored to to counter the Presevet class and thus, required a high top speed, as British intel reported incorrectly a top speed of 19 knots (15 in reality). Engineers, under supervision of Director of Naval Construction, William Henry White. The initial drafts were completed by February 1898, and submitted to the board of admiralty (at the time, headed by George Goschen, 1st Lord, Sir Frederick William Richards, first Naval Lord and Sir Frederick Bedford, Second Naval Lord).

Persevet class

However the latter estimated more work were necessary for a fitting response to the Russians and thus, choose modified versions of the Formidable class, ordered in the meantime to maintain the overall battleship tonnage high up. The latter were essentially incorporated some aspects of White’s design: New armour layout for the bow, no longer an ending transverse bulkhead and instead continuation of the side armour to the stem, but with reduced thickness. With other revisions, this became the London-class battleships.

Back to the “Persevet killers” prospective design: They had to be faster, and still had to retain the same battery and displacement down. The only compromises were found in armour protection, but with a twist: By adopting a revised system for the bow copied on the London class and other perks, some impressive weight savings were achieved. Whiyte thus, submitted the admiralty board a new design on 14 June 1898.

Cornwallis launch in 1901

Reaching 19 knots while keeping displacement still 1,000 tonnes under the Formidable class and same battery could not be achiieve by other way as revising the armour scheme to make it lighter, and other measures. There were significant reductions, and he drew inspiration for the older, smaller Canopus class, not the more modern Formidable/London. Thus, the new battleships were built on a basis 1,000 tons more than the Canopus class, allowing improvements. In the end they had the latest heavy guns, and overall much better armour, 2 knots more in top spee.

The last small revisions were made between June, and others in September. At that date, the final design was approved by the board, and tenders were emitted for shipyards to be answered in the following month. Behind all this was the still persistent “Russian Scare”, present in the Public and maintained by inflamatory press articles. The pressure over this 1898 programme (the first three London-class) almost had the latter cancelled as they were supposedly slower and thus inferior to the Russian Battleships. A “Special Supplementary Programme”, unthinkable in normal peace time, allocated funding for the first four of the Duncans, laid down in record time by 1899 with two more added in the FY1899 programme.

White’s final design was a two-side coin, on one hand, compromised and thus, inferior (in protection mostly) to other true first class battleships, but on the other, they proved way superior to the Peresvets, especially when it appeared at the time of the Russo-Japanese ar that they were much slower than expected, overweight, and with glaring protection issues. In the end, the faster Duncan had less use after the end of the Russo-British naval arms race, and the Russo-Japanese war definitely bown away this threat for good. The six vessels saw service in the Mediterranean, notably at the Dardanelles, Russel and Cornwallis being sunk by mines and submarines.

Design in detail

The Duncan-class were 432 feet (132 m) long (overall) and 75 ft 6 in (23.01 m) in beam, with and a draft of 25 ft 9 in (7.85 m) for a normal displacement ranging from 13,270 to 13,745 long tons, and 14,900-15,200 long tons fully loaded, as there were differences between the six ships.

Overall, their design was quite classic, with a symetrical profile, two bridges with the centerline main turrets fore and aft the battery deck in between, secondary armament in casemates. The two pole masts had fighting tops with smal anti-TB guns, a searchlight, four more being mounted on the forward and aft bridges.

Their hulls were sub-divided in numerous compartments underwater, participating in the ASW defence, with longitudinal bulkheads left void to allow counter-flooding, offset any list to some degree. The idea was there, however there was no sufficient pimping equipment to quickly do the flooding, as other pre-dreanoughts of the time. This came back to haunt engineers duing WWI in two fatal occasions. Longitudinal bulkheads was a noverlty, to keep reserve stability low and making the ships stable gun platforms in rough water if needed.

Complement comprised 720 officers and ratings, and in 1904, HMS Russell had 736 and up to 762 as flagship. By 1915, she had 781. Small boats were carried along the central battery space on davits, and comprosition varied over time and ship, but almost comprised two steam/sail pinnaces and steam launches (Use as picket boats, for landing parties as well as harbour communication and dispatch in the fleet), and cutters, whalers, gigs, dinghies, or rafts in WW1.

For communication, they all had a Type 1 wireless telegraphy set, but HMS Exmouth, the first fitted with Type 2 sets, also replacing the Type 1 on all ships later in their career, except for HMS Montagu, lost at sea. HMS Cornwallis and Russell later had them replaced by Type 3 wireless transmitters, the only ones with such upgrade.

Armor protection

The Duncans just repeated the Formidable class scheme, but reviside for the forward section: It was thinner in general to save weight. White, given their intended role as fast battleships, just discarded the forward transverse bulkhead, in favor of a complete belt, not partial as previous vessels. Here are the details.

- Main belt amidship: 7 inches (178 mm)

- Belt tapering aft: 5 in (127 mm), 4 in (102 mm), 3 in (76 mm), 2 in (51 mm)

- Aft transverse bulkhead; 7 in thick

- Abaft bulkhead; 1-inch (25 mm) armour

- Main armored deck: 1-2 in thick*

- Second deck: 1 in

- Underwater wl deck: 1-2 in

- Main battery turrets: Faces, sides 8 in (203 mm)

- Main battery turrets: Rear 10 in (254 mm), roof 2-3 in

- Main Barbettes: 11 in (279 mm), 7 in below armor deck with 4-10 in inner faces.

- Casemate battery: 6 in (152 mm)

- Ammunition hoists: 2 in

- Fwd Conning Tower (CT) 10-18 in sides

- Aft Conning Tower 3 in sides

*The main deck ran from the stem to the aft bulkhead, connected to belt top, with thinner thickness over the bow.

The second deck covered the central citadel only and sloped down to the belt. Voids created in these spaces were used to store coal acting as additional protection.

Bow and stern had a curved armour deck below the waterline extended from the barbettes to the hull.

Powerplant

Russel’s sea trials

The Duncan-class had two 4-cylinder triple-expansion engines. They drove two shafts, which were inward-turning, with four-bladed bronze screw propellers. Some twenty-four Belleville boilers, small and compact, provided steam. They were located in four boiler rooms, two rooms with eight boilers each, two with four, in order to mitigate flooding. They were all trunked into two closely spaced funnels amidships.

The whole powerplant was rated for 18,000 indicated horsepower (13,000 kW). This enabled a top speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph= as required by the board. Speed trials showed these figures were exceeded to 18.6-19.4 knots (34.4 to 35.9 km/h; 21.4 to 22.3 mph) making them the fastest in this area,

Cruising speed was 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), and at tis rate, they could reach 6,070 nautical miles (11,240 km; 6,990 mi) in one go. In wartime of course, the coal carried was almost doubled.

Armament

Main: 2×2 12-in/40 Elswick

The Duncans received the usual two twin turrets for and aft, four 12-inch (305 mm) 40-calibre guns. Same guns and mountings as for the Formidable and London classes making them cheaper overall due to “mass production”. Barbettes were slightly reduced in diameter for weight-saving, being narrower making also reduced gun houses. Nothing was changed for their BVI-type mountings which still fit in.

-Mounts had a -5 degrees depression and 13.5 degrees elevation; but reloading was at 4.5 degrees to be loaded.

-Muzzle velocity was 2,562 to 2,573 feet per second (781 to 784 m/s).

-They could penetrate a 12 inches armor plate using Krupp steel, at 4,800 yards (4,400 m).

-At maximum elevation, they reached 15,300 yards (14,000 m).

Secondary: 12x 6-in/45

Exmouth’s secondary battery casemates

The secondary battery comprised the usual twelve 6-inch (152 mm) 45-calibre battery in casemates,same as earlier London/Formidable classes. The casemates were sponsoned when reaching the outer sections amidship to improve firing arcs and reducing blast effects on the hull. Two were planned at some popint to be moved on the upper deck to avoid issues in heavy seas, but that this would hamper smooth ammunition suppy from the magazines.

-Muzzle velocity was 2,536 ft/s (773 m/s).

-Penetrate of 6-inches Krupp armour at 2,500 yards (2,300 m) tested.

-Maximum elevation 14 degrees

-Max range 12,000 yards (11,000 m).

Tertiary:

HMS Russel (engraving) showin the 12 pdrs in the bow, behind recesses.

The close quarters torpedo boats defence rested on ten 12-pounder guns, six 3-pounder guns. They were similar to the QF guns used on other battleships of that era, and often one-manned. In complement as usual, the Duncans were given a set of four 18-inch (457 mm) torpedo tubes, submerged in the hull amidship, underwater.

In 1915, they all received a supplementary pair of 3-inch (76 mm) for anti-aircraft defence. HMS Albemarle, Duncan, and Exmouth had them placed on the aft superstructure. HMS Russell had them fitted on her quarterdeck. HMS Cornwallis had them placed atop their forwardmost casemates. In 1916-1917, HMS Albemarle saw all her casemate guns removed but four were relocated in place of the upper 12-pounder battery, two of the latter being removed. They wee placed in shielded pivot mounts. In 1917–1918, all her remaining 12-pounders were removed.

Author’s illustration of HMS Corwallis in WW2

⚙ Duncan class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 132 x 23 x 7,85 m (432 ft x 75 ft 6 in x 25 ft 9 in) |

| Displacement | 13,270-13,745 tons normal – 14,900-15,400 tons FL |

| Crew | 720 |

| Propulsion | 2 shaft TE steam engines, 24 wt boilers, 18.000 hp (13,000 KW) |

| Speed | 19 knots top speed (35 kph, 22 mph) |

| Range | 6070 nmi@ 10 knots (11,240 km; 6,990 mi) |

| Armament | 2×2 12-in, 12x 6-in, 10x 12pdr, 6x 3-pdr 4x 18-in TT Sub |

| Armour | Belt 7 in, Bulkheads, barbettes 11 in, Decks 2 in, Turrets 10 in, Casemates 6 in, CT 12 in |

Read More/Src

Links

dreadnoughtproject.org

The grand fleet; 1914-1916; its creation, development and work, John Rushworth Jellicoe

Naval operations by Corbett, Julian Stafford, Sir, 1854-1922

On battleships-cruisers.co

On historyofwar.org

On worldnavalships.com

On worldwar1.co.uk

Wiki commons open source photos

wiki

Books

Gardiner, Robert. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905

Burt, R. A. (2013) [1988]. British Battleships 1889–1904. Seaforth Publishing.

Corbett, Julian Stafford (1920). Naval Operations: To The Battle of the Falklands, December 1914. Vol. I

// Naval Operations: From The Battle of the Falklands to the Entry of Italy Into the War in May 1915. Vol. II.

// Naval Operations: The Dardanelles Campaign. Vol. III. Longmans, Green & Co.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations, NIS

Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work.

Preston, Antony (1985). “Great Britain and Empire Forces”. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921.

Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record. Chatham Publishing.

Dittmar, F. J. & Colledge, J. J. (1972). British Warships 1914–1919. London: Ian Allan.

Gibbons, Tony (1983). The Complete Encyclopedia of Battleships and Battlecruisers. Salamander Books Ltd.

Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1957]. British Battleships. NIS

Pears, Randolph (1979). British Battleships 1892–1957: The Great Days of the Fleets. G. Cave Associates.

Model kits

Combrig got you covered !

General query “Duncan class” on scalemates

Not a lot to draw. Only Combrig treated the subject, at 1:700 and released the Russel, Albermarle, Montagy, and Duncan.

Gallery

HMS Rusel, Exmouth, Albermarle at the Quebec Tercentenary, 1908

HMS Exmouth – Imperial War Museum (IWM)

HMS Duncan – IWM

HMS Albermarle, the King’s ships 1913

Wartime service

Peacetime service

HMS Duncan was laid down by Thames Ironworks of Leamouth and after launch, was fitted out at Chatham in May 1902, completed in October 1903 for sea trials and commissioned, still at Chatham, on 8 October. She was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet after a short service with the Channel Fleet in February 1905. On 26 September she collided with HMS Albion at Lerwick, being holed under the waterline and the rudder damaged, her sternwalk struck down. On 23 July 1906 she grounded off Lundy Islandwhile trying to salvage HMS Montagu.

She was with the Atlantic Fleet in February 1907, later refitted in Gibraltar until February 1908 and in July, visited Canada (Quebec Tercentenary celebtrations) with Albemarle, Exmouth, and Russell. On 1 December 1908 she went at last to the Mediterranean Fleet, as Second Flagship. After a refit in Malta (1909) she went on her routine service until May 1912, when she was found inside the 4th Battle Squadron of the Home Fleet based in Gibraltar. By 27 May 1913, she was placed in reserve at Chatham, 6th Battle Squadron, Second Fleet, Portsmouth, used as gunnery training ship for reserve, followed by a refit at Chatham in May 1914.

Early wartime service

Prow of HMS Duncan in 1914

While she was in refit, wartime plans called for her class to be regrouped as the 6th Battle Squadron, Channel Fleet, protecting the British Expeditionary Force moved to France. Instead, they were assigned to the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow under Grand Fleet CinC Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. He wanted Duncan and Albemarle, Cornwallis, Exmouth, Russell being assigned back to the the 3rd Battle Squadron for patrols due to a shortage of cruisers. The 6th BS was nullified, and now overhauled, having her sea trials complete, Duncan joined the 3rd Battle Squadron for the Northern Patrol.

Duncan and her four sisters plus the King Edward VII class BS were reassigned to the Channel Fleet from 2 November due to to increasing activity from the Hochseeflotte. Indeed the raid of Yarmouth took place while the 3rd Squadron were dispersed on the Northern Patrol. On 13 November 1914, the King Edward VII-class were sent back to the Grand Fleet, leaving Duncan and sisters alone.

The 6th Battle Squadron was reconstituted on 14 November 1914 to bombard German submarine bases off Belgium, from Portland and later Dover from 14 November 1914. The latter being poorly protected against U-Boats, they were setn back to Portland on the 19th. Next, the 6th BS returned to Dover by December, then Sheerness on 30 December to replace the 5th BS for a possible German invasion.

Until May 1915, the 6th BS was dispersed with Duncan leaving from February to be sent for a refit at Chatham, until July. She was then attached to the 9th Cruiser Squadron patrollin on the Finisterre-Azores-Madeira patrol base network.

Mediterranean service

From August she joined the 2nd Detached Squadron in the Adriatic to reinforce the Italian blocus at Taranto, placed under orders of Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel. However due to the risk of mines and TBs, Revel preferred to wage war with MAS boats and light cruisers, leaving the battleships in Tarento most of the time.

From June 1916, HMS Duncan was reassigned to the 3rd Detached Squadron, Aegean Sea, Salonika base, to watch over Greece under the pro-German Constantine I. Neuyrality was forced by the Entente, landing troops in Salonika in 1915 and tension grew until the coup of August 1916. Duncan sent Royal Marines at Athens on 1 December 1916 while British and French troops defeated by the Greek Army and civilians had to withdrawn to their ships, imposing a blockade.

In January 1917, she returned to Tarento and the next month, was setn back home to be paid off at Sheerness. She served there as an accomodation vessel for ASW boats until April, then moved to Chatham and refitted in January 1918 as accomodation ship (specialized) in Chatham. The war ended and she was stricken and placed for sale by March 1919, sold to Stanlee Shipbreaking Co. of Dover on 18 February 1920, towed there for scrapping by June.

HMS Albermarle was actually the first ship of the serie laid down, on 1st January 1900 at Chatham Dockyard, and completed in November 1903, commissioned at Chatham on 12 November as extra flagship, Rear Admiral for the second division, Mediterranean Fleet. In February 1905 after some training she was reassigned home to the Channel Fleet, always as 2nd Flagship, deputy commander. She next joined the Atlantic Fleet on 31 January 1907, still as 2nd Flagship but under Captain Robert Falcon Scott. At the occasion of manoeuvers, she collided with HMS Commonwealth on 11 February 1907, having her bow damageed and repaired.

In July 1908, HMS Albemarle visited Canada for the Quebec Tercentenary with other BBs and became Flagship, Rear Admiral, Gibraltar (Atlantic Fleet) and by January 1909, refitted at Malta until August 1909. From February 1910 she was reassigned with the 3rd Division based in Portsmouth. Paid off for a refit on 30 October 1911-December 1912 she joined afterwards the 4th Battle Squadron, First Fleet and on 15 May 1913, sent to the 6th Battle Squadron Second Fleet as gunnery training vessel with a reduced crew.

As the war broke out, she had about the same carrier as her sister ships, in the 6th Battle Squadron: Channel Fleet and BEF escort to France, Grand Fleet C-in-C Sir John Jellicoe ordering her with Cornwallis, Duncan, Exmouth, and Russell reassigned to the 3rd Battle Squadron, Scapa Flow from 8 August 1914 (Northern Patrol).

With the King Edward VII class from 2 November they were tasked to patrol for a possible sortie of the Hochseeflotte, which happened with the Yarmouth raid, but she arrived too late. On 13-14 November 1914, the King Edward VII-class were back to the Grand Fleet not Albemarle, with the Channel Fleet as the 6th BS. Tasked to shell Belgium (this never happened) or to block any landing attempt.

The 6th BS was in Sheerness in late December in place of the 5th BS and until May 1915, dispersed. HMS Albemarle joined the 3rd Battle Squadron, Grand Fleet, refitted at Chatham by October 1915. and in November was sent to the Mediterranean with Hibernia (flagship), Zealandia, and Russell (her sister ship). Due to heavy weather, Albemarle being heavily loaded with spare ammunition, had severe damage due to ploughing heavily, and her forward bridge washed away, washing over board all her bridge personnel and the superstructure below mushed inwards.

Her repairs complete on December 1915, she was back to the Grand Fleet instead, and by January 1916, was sent in North Russia, Murmansk, as guard ship and icebreaker, flagship of Senior Naval Officer, Murmansk. Back home in September 1916, she was paid off at Portsmouth, freeing crews and was refitted at Liverpool in October-March 1917. Placed in reserve, Devonport she lost her main battery guns, having only remaining her upper 6-inch guns by May 1917.

In April 1919, she was used as accommodation ship at Devonport for the Gunnery School, but sold on April 1919 to Cohen Shipbeaking Company and on 19 November in Swansea prepared for BU, which started in April 1920.

Named after William Cornwallis (an amiral of the time of the American revolution) she was laid down by Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company, Leamouth near London, her launching ceremony being subued due to the Court mourning for the just deceased Queen Victoria, and still the launch attracted a crowd and was witnessed by diplomats from other naval powers. Armed in Chatham Dockyard and completed by September 1902 for sea trials, she was declared operational on 9 February 1904.

She relieved HMS Renown in the Mediterranean Fleet and later collided with the Greek brigantine Angelica (17 September), with little damage. Back to the Channel Fleet in February 1905, Atlantic Fleet on 14 January 1907, refitted at Gibraltar (January-May 1908) and Second Flagship, Rear Admiral on 25 August 1909. In August 1909, she was back in the Mediterranean Fleet, Malta and later as part of the 4th Battle Squadron based at Gibraltar, Home Fleet. Reduced crew as part of the 6th Battle Squadron, Second Fleet from March 1914.

From August 1914, her entire class as the 6th Battle Squadron was to serve in the Channel Fleet and patrol the English Channel and cover the BEF. Instead she was sent in the Grand Fleet, requested by Jellicoe, to be in the 3rd Battle Squadron for the northern patrol and with the King Edward VII class were later transferred to the Channel Fleet, later the 6th BS was recreated there. Cornwallis was later detached, assigned to West Ireland command, Clew Bay, Killarney Bay, until January 1915.

The Dardanelles Defences

From January 1915, she was ordered to the Dardanelles, reparting Portland on 24 January 1915, arriving in Tenedos under Admiral Sackville Carden, starting operations on 13 February 1915. HMS Cornwallis was part of an entent fleet of six British and French battleships selected for the first attack on 19 February under VADM John de Robeck. She was tasked to silence the “Orkanie” coastal battery, starting at 09:51. She had the honor of firing the very first shots of the Dardanelles campaign.

However she could not take fixed position due to her defective capstan, unable to dropp anchor and ordered to retie. Cornwallis was replaced by HMS Vengeance and tasked to spott positions for HMS Triumph and the battlecruiser HMS Inflexible. At 15:00, Cornwallis and Vengeance joined Suffren bombarding Kumkale at close range, using her 6-inch guns to deal with the “Helles” battery. Cornwallis came under fire but had not significant damage and due to the sun silhouetting the vessels at 17:20, Carden a general withdrawal.

HMS Corwnallis broadsiding Suvla Bay defences en Dec. 1915

On 25 February the attack was ordered again by de Robeck (flagship HMS Vengeance), leading the assault with Cornwallis and followed by French Admiral Guépratte, flagship Suffren and with Charlemagne. They attacked the defences at close range, other providing longer range to shrapnel the gun crews overhead. De Roebeck was given order to make run into the narrows at 12:15 and later Carden ordered minesweepers to enter the straits in turn and commence operations. Cornwallis was later detached to return to Tenedos.

The Anglo-French fleet launched another attack on 26 February and sent raiding parties ashore, silencing Kumkale, “Orkanie”, Sedd el Bahr. Attack the next day was marred by poor weather. On 2 March, Cornwallis joined the 1st Division, tasked to silence fortresses further up the straits, Dardanus and Erenköy. She engaged six howitzers located at Intepe and swapped to Erenköy, also suppressed. She was bombarded Dardanus when de Roebeck recalled his ships, mission accomplished.

HMS Cornwallis, stern view

The 4 March raid saw Cornwallis stationed inside the strait in spoort of a landing party of Royal Marines from SS Braemar Castle at Kumkale. Before stiff Ottoman resistance Cornwallis and HMS Irresistible tried to silence Ottoman defences, but counter fire was too heavy and the marines retreated. Cornwallis, Agamemnon, and Dublin covered their evacuation. On 5 march, new attack, but this time the stars of the show would be HMS Queen Elizabeth, being able to reach the inner fortresses from the safety of the Aegean coast due to her range. Cornwallis, Irresistible and Canopus made spotting for her, until Poor visibility and more accurate Turkish fire prevented Queen Elizabeth to complete her mission.

On 10 March, Cornwallis with Irresistible, and HMS Ark Royal sending her spotter planes, screened by HMS Dublin in the Gulf of Saros had to make a recce of Ottoman defences further up the Gallipoli peninsula. Weather prevented seaplanes to operate and Cornwallis bombarded instead the town of Bulair. In Tenedos, she was reassigned to the 2nd Division but on 18 March did not take part, the day three battleships were sunk by mines and gunfire. British and French commanders ultimated decided that only landings would do.

She covered the Landing at Cape Helles on 25 April as part of the 1st Squadron, at the southernmost landing sites, W Beach and V Beach. She was supported by HMS Implacable and HMS Euryalus, flagship of RADM Rosslyn Wemyss (1st Squadron). Cornwallis carried and transferred soldiers to trawlers, then to small boats at V Beach. Wemyss instructed Cornwallis to shell located Ottoman defences until the landing was complete, and made point support, notably covering the landing ship River Clyde. She shelled the heights and 10:00, a beachhead was secured. Cornwallis left to support River Clyde beached under heavy fire at Sedd el Bahr, until the landing was cancelled.

View of British stores burning during evacuation from Gallipoli

During the advance on Krithia on 28 April, HMS Cornwallis provided gun support (First Battle of Krithia) but it failed due to the Ottoman resistance. In May, a rotattion system between stations off beachheads was started. Cornwallis was assigned to the right flank at Kereves Dere (12–13 May) with HMS Goliath, which was later sunk by the destroyer Muavenet-i Milliye, Cornwallis pick up survivors. Next she was off Suvla Bay by December, supporting the evacuation and making a tremendous bombardment on 20 December to destroy all quipment left, spending her remaining 500 12-inch shells as well as 6,000 6-inch shells, being last capital ship to leave Suvla Bay.

Transferred to the Suez Canal Patrol with Glory and Euryalus from 4 January 1916 she also was part of the East Indies Station until March 1916, escorting convoys to and from the Indian Ocean. Back to the eastern Mediterranean from March 1916 she ws refitted in Malta (May-June) and from 9 January 1917, she was ambushed and torpedoed by U-boat U-32 (Kptn Kurt Hartwig) hit on the starboard, some 60 nm east of Malta. Some stokeholds were flooded and she listed 10° starboard, corrected by counter-flooding, but remained immobilised. Soon U-32 reload her torpredo tubes and made another attack, while trying to escape depth charge attack from escorting destroyers.

hms cornwallis sinking 9 January 1917

Just as preparations to take her under tow, 75 minutes after the first hit, she was hit by another on starboard. This time the flooding became uncontrollable and she rolled to starboard an turned over. 50 men died in the explosions, however her hull now overturned and still maintained by plenty of air trapped inside, she stayed float, allowing the rest of the crew to evacuate. 30 minutes after, she sank for good.

HMS Exmouth was built by Laird Brothers, Birkenhead, started on 10 August 1899 and completed at the Nore in May 1902, armed and completed at Chatham Dockyard which was delayed due to labour strikes until May 1903. She was commissioned at Chatham on 2 June 1903 and assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet until back home in May 1904. The 18th, she became Flagship, VADM Home Fleet, Sir Arthur Wilson, later known as the Channel Fleet, and conceded her flag away in April 1907, reduced to nucleus crew and reserve, refit at Portsmouth.

Fully recommissioned on 25 May 1907 as Flagship for the Atlantic Fleet’s VADM, by July 1908 she visited Canada for the Quebec Tercentenary with three sister ships. On 20 November she was reassigned to the Mediterranean Fleet, still as flagship, refitted in Malta in 1909. Nothing much happened of note until 1912 but a fleet reorganization which saw her in the 4th Battle Squadron in Gibraltar and still as flagship, by July. In December 1912 she was refitted at Malta and returned on 1 July 1913 to Devonport Dockyard in commissioned reserve, 6th BS of the Second Fleet, a gunnery training ship in Devonport like her sister and fully recommissioned when the war broke up.

Her career in the 6th Battle Squadron with her sisters is basically the same: Channel Fleet, Grand Fleet, 3rd Battle Squadron in Scapa Flow, and after a refit in Devonport, she sailed to help the stranded HMS, hit by a mine north of Ireland on 27 October 1914. Exmouth (from Lough Swilly) arrived too late as the dreadnought was already abandoned before capsizing and exploding, picking up some survivors. She was back in the Channel Fleet, soon again the 6th Battle Squadron, latter based in Portland in late November.

Exmouth and Russell however did bombard Zeebrugge as planned, on 23 November 1914, from 6,000 yards (5,500 m). In additon to wrecking the harbor, they cut the railroad lines and flattened the station, hammered the coastal defences, spending 400 shells. Dutch observers confirmed significant damage. But all was repaired in a shot notice and the Royal Navy prevented further operations of that kind, deemed too risky. The 6th BS was in Dover by December, then Sheerness on 30 December, relieving the 5th BS.

In January-May 1915, her unit was dispersed and HMS Exmouth left for the Dardanelles on 12 May as Flagship, RADM Nicholson, arriving there with HMS Venerable. There, the C-in-C believed their coastal bombardment of Belgium made them the most skilled, and they were given extra-heavy anti-torpedo nets. However after the loss of HMS Goliath, Triumph, and Majestic, she was the only one to remain off the beaches at Kephalo, Imbros.

By 4 June with HMS Swiftsure and Talbot she sailed to Cape Helles in support of a landing at Achi Baba. Reports of submarines had them steaming in circles while firing, which ended not as very efficient. The attack failed and by July, Kephalo station received an anti-submarine boom. She covered another Allied attack at Achi Baba in August, without results. By November 1915 she left Kephalo for the Aegean Sea as Flagship, 3rd Detached Squadron in Salonika. The fleet assisted the French Navy in blockading the Aegean coast of Greece and Bulgaria. Watching also the Suez Canal Patrol.

HMS Exmouth at Kephalo (painting)

On 28 November 1915, she hosted the personal of the British Belgrade Naval Force evacuated from Serbia and until December 1916 took par tin the fleet presuring the government of Greece to take sides. In Salamis, she landed a party to seize the port and neutralize the Greek fleet, and covered Royal Marines in Athens on 1 December and the following blockade before bing reassinged to the East Indies Station in March 1917 for convoy escort duties to the Indian Ocean.

By June 1917, she she stopped at Zanzibar, The Cape and Sierra Leone and went back to Devonport in August 1917, to be deactivated, free crews, placed in reserve at Devonport until April 1919 and be used as an accommodation ship from January 1918, sold from April 1919, purchased on 15 January 1920 and scrapped in the Netherlands.

HMS Montagu construction sarted on 23 November 1899 and she sarted sea trials in February 1903, commissioned on 28 July in Devonport, moving to the Mediterranean Fleet. By February 1905, she was transferred back to the Channel Fleet. Unlike her sisters she would never see WWI: In late May 1906, she tested new wireless telegraphy in the Bristol Channel and by 29 May, she was anchored off Lundy Island, failing to pick up messages from the test station.

Her captain fatefully then decided to have her moved to the Isles of Scilly. Hwever her path was made difficult by Heavy fog. She eventually reversed course back to Lundy Island, after four hours. Unfortunately her navigator miscalculated the course, so that she veered two miles off her planned track and encountering a pilot cutter cruising nearby, stopped to come alongside it and require guidance and bearing for Hartland Point.

The cutter’s captain gave accurate data, but Montagu’s Captain, still on a wrong path, dod not believed him, restarted the engines and moved ahead while the cutter’s man deperately shouted back they would soon be on Shutter Rock. As ge recalled and told the press later, he saw the battleship disappear into the mist and ten minutes after, the powerful, distant freight train rumble as she ran aground. At 02:00, 30 May, the captain started an inspection discovering a 91-foot (28 m) gash starboard on the rocks.

After frantic machinery tests, it was soon found she was stuck and needed help, while slowly flooding. After 24h her starboard engine room wasn underwater, as the boilers. Counter-floodeing in the port engine room avoided further list but she lost all propulsion. Divers inspected further the hull, discovering it was even more serious than expected, and suspected her bottom was also badly damaged and leaking. The port propeller shaft was torn off, and there were serie of holes and gashes in the plating at several sections. The starboard bilge keel was ripped orr and the rudder. She still stayed on a fairly even bottom and so the captain thought she could be salvaged anyway.

The Royal Navy at the time however, had no dedicated salvage unit, even though for that kind of damage. Frederick Young, a former RN captain now chief salvage officer at the Liverpool Salvage Association was at the time the most thought-after expert on marine salvage in the country and came after to advise Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson (Channel Fleet CinC). The navy at first wanted to try lighten the ship, removing artillery and equipment, pump out water and patch the hull.

By late June, 20 pumps were at work and had a total capacity of 8,600 tonnes per hour. But pumping work was marred by the internal subdivision and the need of matching the high tide before patching the hull? The team eventually gave up. Next it was proposed to remove armour plating and erect caissons for extra buoyancy. Also to use a powerful air pump to blow water out of the hull. But caissons broke free while the air pump failed to reeach the desired power.

At some point, her sister HMS Duncan also ran aground while trying to tow her out, in vain. However the latter was freed. In the summer of 1906, salvage efforts were suspended for the year. Until 1907 it was believed the team would came with new plans. But this was cut short after a torough inspection on 1-10 October 1906. Experts saw the action of the sea alone was driving her ashore, bending and warping her hull further to the point her seams opened and her deck planking came apart, her boat davits collapsed. The navy eventually decided it was oo late to save her, and after further material was removed she was left there.

Later the Western Marine Salvage Company (Penzance) did extra salvage, looking for scrap metal, stripping her for 15 years. Before that, a court martial held aboard HMS Victory blamed the thick fog and faulty navigation from Captain Thomas Adair, and his navigation officer, Lieutenant James Dathan. Dismissed, the latter lost two years of seniority in rank, but still served in the RN afterwards. The wreck site still prsents remnants that are today a popular diving location. In September 2019 the British Government granted protected status to the site after years of pillage.

HS Russel in 1909 after refit. Note the funnel’s identification bands.

HMS Russell (named afte the 1st Earl of Orford, RN CinC in the 17th century) was built at Palmers Shipbuilding and Iron Company, Jarrow between 11 March 1899 and launch on 19 February 1902 followed by completion at Sheerness and Chatham, until February 1903. She was the only one apparently during her trials reverting to the Victorian-era black and buff paint scheme. Once commissioned, she reverted to the standard grey paint scheme.

From 19 February 1903 she was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet, until April 1904, then back in the Home Fleet, later Channel Fleet, and Atlantic Fleet in February 1907. BY July 1908 she visited Canada (Quebec Tercentenary) like her sisters but on 16 July collided with the cruiser HMS Venus with little damage. In 1909 she received a unique overhaul with new traversing and elevation gear, sights and telemeters. She also had unique painted identification bands on the funnels and by 30 July returned to the Mediterranean Fleet, passed into the 4th Battle Squadron in Gibraltar

Back home in August 1912 for a refit, she stayed in limited service before being reduced to nucleus crew by September 1913 (commissioned reserve, 6th Battle Squadron) and from December as Flagship at the Nore, having her anti-torpedo nets removed and never reinstalled. By 7–8 July 1914, she ferried members of the British government headed by Lord Beauchamp from Dover to Guernsey as a monument to Victor Hugo (which lived there) was unveiled, assisted by representatives from France came onnboard the cruiser Dupetit-Thouars.

The rest of her career is a mirror of the other, so we will not returned intio the details. However as part of the 6th Battle Squadron she was sent with Exmouth to perform a bombardment of Zeebrugge on 23 November 1914, from 6,000 yards (5,500 m), sharing 400 shells spent between them, but with apparently little results for the long terms. That mission was the last one before the introduction of specially-made monitors for the same task. It was just too risky for the high command, despite a destroyer escort. On May 1915, the 6th BD was dispersed and only Russell and Albemarle remained with the Grand Fleet, making training exercises in Scapa Flow. Russell later left the squadron in April 1915 for the 3rd BS in Rosyth, refitted in Belfast (October–November).

On 6 November 1915, HMS Hibernia (flagship), Zealandia, Albemarle, and Russell were sent to the Dardanelles, to take part in the Gallipoli Campaign, for a tour of duty starting in December from Mudros, assisted by Hibernia in support. he only sortied to cove the evacuation of Cape Helles (7-9 January), being the last battleship to leave the area and becoming Divisional Flagship. In the eastern Mediterranean she was based in Malta. On 27 April 1916 while underway for exercizes, she struck two naval mines from U-73.

HMS Russell with a short seaplane flying over (IWM)

A fire started aft which became untrollable, and the ship experienced listing until order was given to abandon ship. The fire apparently cooked off the aft 12-inch magazine and detonated it, which blasted away the enormous turret. Fortunately for her crew, she sank slowly in part due to her numerous underwater compartments, which jusy blasted after a certain water pressure was reached, delaying the whole process. Most of the crew was rescued while 27 officers and 98 ratings went down with HMS Russel. As an interesting note John H. D. Cunningham served aboard as lieutenant commander.

As a reverse face of wha t was said above, naval historian R. A. Burt thought the insufficient internal subdivision limited effort of counter-flooding the ship, which contributed to her loss, as for her sister HMS Cornwallis, torpedoed. Her wreck was resiscovered in 2003 under 63 fathoms (115 m), 3.2 nautical miles off the Delimara peninsula. Her stern was missing.