The middle Condottiere

The group IV of the Condottieri cruisers “superclass” included the Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta (1934) and Eugenio di Savoia (1935), very similar in design and appearance to the previous Raimondo Montecuccoli class. These fleet cruisers were the last armed with “only” (given their tonnage) eight 6-in guns (150 mm). They improved on the previous class on many points, setting them apart eventually despite the obvious similarities. This incremental process allowed to reach the next big step forward that was the Duca Degli Abruzzi class in 1936.

The E.F.Duca D’Aosta class was scheduled and planned for the very same 1931-33 naval programme as the Montecuccoli class. There was however a full year gap between their laying down: Both the Group III cruisers were laid down in Ansaldo and CRDA in April (Attendolo) and October (Montecuccoli), while the lead ship D’Aosta was laid down in OTO in October 1932. This full year allowed engineers to gradually improve on their previous designs while keeping the essentials. For various reasons (such as range and habitability) it was preferred a larger hull, which implied greater displacement, requiring greater output, but also allowing for some extra protection and better balance overall. Still, protection remained light.

Both cruisers in concert, prewar. During the war they were in separated units most of the time.

Both cruisers would have a long active life. They participated in several important battles and survived into the co-belligerence period, but were sent after the war as war reparations to Greece and USSR, as Elli and Kerch, new flags under which they served for many more years, like the Montecuccoli which also seen cold war service with the Marina Militare.

Design Changes

Savoia in 1942 and 1943

The major concern of the engineers was to increase protection, even compared to the Montecuccoli class. Therefore they opted for a full, thicker armor, also reflected in the layout plan, which had a larger volume. Yet she was still better protected, between 3 to 4-in (100 and 60 mm) versus for example a mere 1-in at most on Cadorna. This was done by a sacrifice: Speed, and yet based on a better output, 106,000 hp versus 95,000 on the previous class. Displacement But they still managed to crank up 37 knots on trials. In practice it was below 36.5 knots. Armament did not changed, except for a better AA artillery with 4 twin Breda 37mm mount, no 40 mm as on the Montecuccoli.

Cruiser Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta

Hull Construction and general design

The D’Aosta was virtually a repeat of the montecuccoli design but they were designed with almost a year gap, for the same programme. This left time for plenty of incremental improvements. The hull was the same in shape and form, with the remarkable amount of flare at the bow, which looked from above larger than the more slender poop. New sections were added, and the hull was lenghtened, the making it roomier with an extra 39 feets (12 meters) long, 3.6 feets (1.10 meters) at the beam, and 1.6 feets (0.5 meters) of additional draft, or 186.9 m (613 ft 2 in) overall for 17.5 m (57 ft 5 in) in beam and 6.1 m (20 ft 0 in) draught. Tonnage of course rose to 8,300-8,600 tons standard versus 7,400 on the Montecuccoli, and up to 10,300-10,600 tons fully loaded. Their standard was the Group III cruisers’s full load…

Superstructures and general outlook were the same, and in fact Intel service in all admiralties had problem distinguishing Group III and IV, understandably. Main and secondary Artillery was placed exactly the same, they had identical silhouette with same forecastle, proportions, minimalistic tower bridge supporting the main telemeter and FCS, two large funnels with raked caps, an amidship catapult, same tripod mainmast just at the base of the aft funnel. The only light difference was due to the greater powerplant, making the aft funnel the same size of the fore funnel, unlike Group III cruisers. That was still hard to spot from binoculars. As for the crew, they were manned by 27 officers and 580 ratings. They carried 8 service boats amidships on davits, later reduced in wartime to four, but with extra inflatable rafts.

Armour Layout

To summarize, it was improved enough compared to the Cadorna and the Group III to not consider these “tin-clad cruisers”, but still unsufficient overall. It did not reached the level of Group V cruisers, which went straight for the Washington limit for this, on the same hull basically. For turrets it’s their frontal arc, front plates and sides figures. For the CT, the second value is the roof. Former Group III are marked with a star.

Main belt: 70+35 mm (2.8+1.3 in)/60+25 mm*

Bulkheads: 50-30 mm (2-1.2 in)/40-20 mm*

Deck: 35-30 mm (1.4 in)/30-20 mm*

Barbettes: 70-50 mm (2.7-2.1 in)/50-30 mm*

Turrets: 90 mm (3.5 in)/70 mm*

Conning tower: 100-40 mm (3.9 in)/100-25 mm*

Communication Tube: 30-20 mm (1.2-0.7 in)/30 mm*

Powerplant

Cutaway of the Montecucoli showing the location of respective boiler rooms and truncated exhaust pipes.

The propulsion comprised two propeller shafts driven by Parsons (Aosta) and Belluzo (Savoia) turbo-reducer groups turbines, fed by steam provided by six water tube boilers of the Yarrow (Aosta) and Regia Marina (Savoia) type, oil-fired with injectors and superheaters. Water flowed through pipes heated externally by combustion gases exploiting to the full all the heat coming from the burners, boilers walls and exhaust gases. They required a special steel and special welding techniques to withstand high temperatures. Total output was 110,000 hp, to compare with 106,000 on Group III,

allowing a maximum speed of almost 36.5 knots, a bit less than Group III due to the larger hull. They had a roughly similar range based on 1,653 tons of oil in normal conditions, at cruise speed 14 knots, of 3,900 nautical miles. To compared on Group III this was respectively 1,275-1,295 tons for 4,122 nmi (7,634 km) at 18 knots, so they were not good walkers and range was decreased despite additional fuel on board.

Cutaway of the previous Attendolo (src)

But the most important was the arrangement of boiler rooms: Previous group had four forward, two aft groups and funnel size accordingly. On group IV, they were placed in two groups and three boilers fore and aft, for a heavenly number of smoke ducts making funnels of identical size. Each boiler room was also positioned in a separate compartment.

Armament

Main: 4×2 6-in/53 (152mm) OTO

Main guns blazing in heavy seas on Savoia in 1937.

The main armament comprised eight 152mm/53 A-1932 model gun (6 inches/53) from OTO, in separated single mounts but twin turrets, two superfiring forward and two aft. They used semi-automatic loading guns allowing reload up to 15° elevation. The individual mounts and larger separation, like on the Montecuccoli class, authorized less interference and thus favored accuracy.

See more on the weapons section

Sec: 3×2 100 mm/47 DP M28 OTO

The main anti-aircraft armament consisted of six 100/47mm OTO guns modello 1928. Original design was going back to the 1907 Škoda 10 cm K10. First pattern was 1924. They were distributed in three twin mounts like the previous Montecuccoli class, and could take on anti-ship roles as well. Relevant in 1934, but no longer by 1940 they were unable to follow the nex generation of aircraft or to repel diving attacks. By default the tactic was to use them for barrage fire. For their replacement, it was planned to install the new 90/50 mm model A-1938 developed by OTO for the Regia Marina, in single mounts, much faster and stabilized. They were adopted on the rebuilt Duilio and Littorio only however. See more on the weapons section

Torpedo Tubes and ASW

Torpedo Tube banks on Savoia

The torpedo armament consisted of six 533 mm (21 inches) torpedo tubes, distrubited into two triple banks that located on deck, amidships, abaft the funnels.

The models fired were same as the Montecuccoli class: 53.3 cm (21″) Si 270/533.4 x 7.2 “M” models with the following specs:

Total weight 3,748 lbs. (1,700 kg) for 23 ft. 7 in. (7.200 m)

Explosive Charge: 595 lbs. (270 kg)

Wet Heater, 4,400 yards (4,000 m)/46 knots or 8,750 yds/35 knots or 13,100 yds/29 kts

Anti-submarine armament: The Aosta class cruisers carried each two depth charge throwers and two racks aft.

Paravanes: Both cruiser carried four of them. Used as mine cable cutters, Paravanes were present on all Italian cruisers.

AA Armament

The main anti-aircraft armament consisted of:

-8 Breda 37mm/54 heavy machine guns in four twin mounts. They were located

They were proved against low-flying torpedo bomber attacks.

-8 13.2mm/76 Hotchiss heavy machine guns in four twin mounts. Completely inadequate in 1940 but yet still also shared (in caliber) by French, British and US ships. They were located around the bridge.

Note that by the Autumn of 1943 both kept thir six twin 13.2mm/76 Breda but had in addition (and replacement of their 100 mm apparently) ten single 20mm/70 Oerlikon AA guns installed. In 1944, two more added on both ships again. There were no other modifications but the removal of torpedo tubes, catapult and seaplanes to spare weight and stability.

Duca d’Aosta in 1941

Sensors

Like most Italian ships in 1940, these cruisers had no radar. With war lessons and availability, by mid-1943, Emanuele Filiberto Duca d`Aosta received a German FuMo 39 radar, provided by its ally. From there, by August 1943 her sister ship Eugenio di Savoia inaugurated the Italian Gufo or EC.3/ter radar. By the Summer of 1944 Duca d’Aosta had both a FuMo 39 radar and a British type 286 radar, quite a unique combination !

By early 1945, she only retained her British type 286 radar. USSR apparently fitted Kerch with better sensors while under service (according to navypedia): Giuys and Redan radars. This radar is easy to spot aft of the tower. Greece did received modifications as its radar was installed at the end of a sturdier lattice mast aft of the tower bridge. Presumably the same EC.3/ter radar, but apparently later replaced by an SO-8 surface radar. Src

The FuMo 39 (Funkmess-Ortung) Radar was for direction finder, active ranging. Derived from FuMo 21, which had a mere 10 nm range.

The Type 286 radar made by ECKO had a frequency of 214 MHz. It was a VHF-Band with a PRF of 200 to 800 Hz, 2 µ pulsewidth, 6 kW for a 25 NM (≙ 46 km) range.

The EC.3/ter Or “Gufo” was had a 400–750 MHz Frequency, 500 Hz PRF, 6° (horizontal), 12° (vertical) Bdwt, 4 μs Plswt, 3 RPM, 10 KW for a 25–80 km (16–50 mi) range. This was the first Italian radar, invented by navy technicians Ugo Tiberio, Nello Carrara and Alfeo Brandimarte in 1936–1937, stopped in 1941 but revived after Cape Matapan. First tests on TB Giacinto Carini in April 1941. Produced by SAFAR (150+ units) but only 12 on various ships by 8 September 1943. It was however used “officially” rarely, since the German informed the RN not to use it long range, believing it could be spotted by British radar warning such as the Metox (which was not opertational before mid-1944). It seemed to have seen a wide use, but was not mentioned on logbooks. Only Scipione Africano used it in combat on 16-17 July 1943, sinking MTB 316.

On board Aviation

IMAM Ro 43 aboard Trieste..

RO 43 being towed back on the catapult, on Eugenio Di Savoia (Luce, src below).

The unit embarked two IMAM Ro.43 sea reconnaissance seaplanes two-seater biplanes (300 kph, 1,000 km range). They were launched from the admidship catapult, in between funnels, and max capacity was three, with one on catapult and two on rails on each side, wings folded. They could be picked up with a little traverse by the catapult. The Ro.37 was however too flimsy for landing at sea and be recuperated aboard, and so often instead looked to land on shore.

About the names

Eugenio di Savoia was named after Eugene of Savoy, a military strategist and general of the late 16th century, which he served with distinction. Prince Eugene Francis of Savoy–Carignano or Carignamo (18 October 1663 – 21 April 1736) “Prince Eugene” became a field marshal both in the army of the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Habsburg dynasty and one of the most successful military commanders of his time, rising at the top of Imperial court in Vienna, but brought up in the court of King Louis XIV of France, but was denied service in the French army, transferring his loyalty to the Holy Roman Empire, with a career spanning six decades. Victories counts the fields of Blenheim (1704), Oudenarde (1708), Malplaquet (1709), Battle of Turin (1706), battle of Petrovaradin (1716) and Siege of Belgrade (1717). The 1934 cruiser also had the motto of the Aosta Alpine battalion engraved.

Resources

Books

Arrigo. Petacco, Le battaglie navali del Mediterraneo nella seconda guerra mondiale (Mondadori)

Michael J. Whitley, Cruisers of World War Two, Londra, Arms and armour Press 1995

Robert Gardiner, Stephen C. All the World Fighting’s Ships 1922-46 and 1947-1995

James Joseph Colledge, Ben Warlow, Ships of the Royal Navy: complete record (Chatham 2006)

Gianni Rocca, Fucilate gli ammiragli. La tragedia della marina italiana nella seconda guerra mondiale (Mondadori 1987)

Gino Galuppini, Guida alle navi d’Italia dal 1861 a oggi, Milano (Mondadori)

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, L’organizzazione della Marina durante il conflitto. Tome II. Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare 1975.

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina Italiana nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Vol. IV. Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare 1959.

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina Italiana nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Vol. V. Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare 1960.

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina Militare nel suo primo secolo di vita 1861-1961. Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare 1961.

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina dall’8 settembre alla fine del conflitto. Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare 1971.

Giuseppe Fioravanzo, La Marina Italiana nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Vol. VIII. Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare 1964.

Raffaele De Courten, Memories Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare, 1993.

Pier Paolo Bergamini, Le forze navali da battaglia e l’armistizio. Rivista Marittima 2002

Aldo Cocchia, Filippo De Palma, La Marina Italiana nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Vol. VI-Vol. VII Ufficio Storico della Marina Militare

Luis de la Sierra, La guerra navale nel Mediterraneo: 1940-1943. Mursia 1998

Erminio Bagnasco, M. Brescia, Cacciatorpediniere classi “Freccia/Folgore”. Albertelli, 1997.

Links

On regiamarinaitaliana.it (archive)

On wiki.warthunder.ru

Italian Torpedoes on navweaps.com

On uboat.net/

On navypedia.org/

Kriegsmarine radars on navweaps.com

On associazione-venus.it – many photos

on alchetron.com

On agenziabozzo.it

Kerch 1:700 Kombrig on scalemates.com/

1:350 Fine scale models kit review on modellmarine.de

Videos

Catapult Launch on Di Savoia (original Luce Footage)

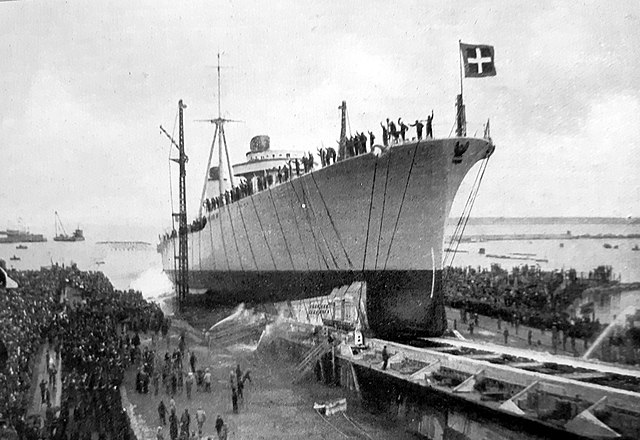

Launch ceremony of Di Savoia

On world of warship

Same, on “armada”

Model Kits

An extract of Profile Morskie 1/400 shiowing the unique camouflage of D’Aosta1/700 Kombrig kit of the class on scalemates

Kit review on icsm.it/regiamarina/

It was also done in 1:1200 by Xpforge and is available for print.

Profiles:

Author’s profile

Eugenio di Savoia in 1936, showing her two-tone livery, dark hull, light superstructure, quite common at the time. Note also the all metal covering of the forecastle deck. During WW2, aerial recoignition white-red bands were painted. src regiamarinaitaliana.it (archive)

The famous and atypical camouflage of E.F. Duca D’Aosta by the time of Operation Harpoon

Eugenio di Savoia at the time of Operation Harpoon. She would receive later another variation of the same with larger “loops” later.

In video games, Duca D’Aosta is a “special” in world on warships.

Career

Both of Group IV survived the war and were awarded to the USSR and Greece in war damage. Under the name of Kerch the first served until 1958-59 as auxiliary cruiser, the second under the name of Helle until 1964.

Cruiser Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta

Emmanuele Filiberto Duca D’Aosta (referred to there simply as “duca D’Aosta”) was started on October 29, 1932 in OTO shipyard, Livorno. She was launched in 1934, commissioned in 1935. First captain was Alberto Da Zara (from 11 July 1935), and she spent her early years in training, after shakedown cruiser, fixes, and fleet exercizes. Nothing much happened until 1938, when she had a new captain, Carlo Balsamo di Specchia.

That year, she departed with her twin Eugenio di Savoia for a circumnavigation of the globe, from Naples on November, 5, 1938, as part of Mussolini’s propaganda campaign. It was only interrupted by the outbreak of World War Two. At the time, both cruisers were in South America. Their initial return was scheduled for July 25, 1939, but it was initially in March, with La Spezia as destination.

They eventually reached La Spezia and were reassigned to the VII Cruisers Division, II Fleet Squadron. They were joined soon by Montecuccoli, Muzio Attendolo under command of Admiral Sansonetti.

Battle of Puntla Stilo (9 July 1940)

Duca D’Aosta took part in the battle of Punta Stilo, first major naval battle between the Regia Marina and Royal Navy. Details could be found there. At the time she was under command of Franco Rogadeo, from 6 September 1939.

On 2 August 1941, after Greece and Crete fell to the Germans, Duca D’Aosta, Garibaldi, Duca degli Abruzzi and the destroyers Alpino, Bersagliere, Corazziere and Mitragliere were sent in Navarino (Greece) tp protect troopship and supplies. They secured the Eastern Mediterranean against any British attacks from Haifa.

Duca D’Aosta in 1941

1st Battle of Syrta

On December 17, 1941, Duca D’Aosta escorted M 42 convoy (cargo ships Monginevro, Naples and Vettor Pisani plus Ankara (German)). This was answered by a British attack, and the 1st battle of the Sirte. As part of the close cover force, along with the destroyers Camisa Negra, Ascari and Aviere, they protected the battleship Duilio and VII Cruiser Division under command of Admiral De Courten.

Battle of Pentelleria (15 June 1942):

In June 1942, Duca D’Aosta took part in the mid-June battle as part of the VIII Cruisers Division with Duca d’Aosta and Garibaldi. She was under command of Luciano Bigi from February 26, 1942. The VIIIth Division was under command of Admiral De Courten, which choosed Duca d’Aosta as flagship. He left Taranto with the Ist Squadron (Garibaldi, Littorio) as part of the interception group of the British convoy. There was a German liaison personael to the Luftwaffe to coordinate operations on Gorizia.

D’Aosta under fire (Phyrexian coll.)

The Italian formation was preceded a screen of destroyers, with Legionario forward of it, equipped with a German Fu.Mo 21/39 De.Te. radar (a first for Italian ships). HMS Burdwan and Kentucky, already on fire due to air attacks, were finished off by gunfire from Raimondo Montecuccoli and Eugenio di Savoia. The operation was called “Harpoon” on the British side, and was a tactical victory for the axis, destroying the convoy and sinking the two escorting destroyers, damaging a cruiser, while the Regia Marina lost no ships but had a destroyer damaged and 29 aircraft lost. D’Aosta was under command of Vessel Captain Temistocle D’Aloia from March 16, 1943.

Duca D’Aosta showing her camouflage in June 1942

The Raid on Palermo (August 1943):

In August 1943, Admiral Fioravanzo (VIII Division) planned to shell Palermo just retook by the allies. But it took until 6 August to gather the forces, Garibaldi, Aosta, in Genoa to be mustered at Maddalena. Garibaldi had turbines issues and down to 28 knots. Aerial reconnaissance signalled unknown ships en route to intercept them and Fioravanzo in inferiority order renounced and folded bacl to La Spezia on 8 August.

The fleet moves to Genoa

At 17:00 on 9 August the two cruisers left La Spezia for Genoa escorted by the destroyers Mitragliere, Carabiniere and Gioberti. The first were in the lead followed by the two cruisers in a row and the to remaining DDs. However underway they were ambushed south of Punta Mesco by HMS Simoon. Six torpedoes were launched, two hitting Gioberti astern which immdiately broke in two and sank with all hands. Carabiniere went on chase and depht-charged it some damaging the S class submersible’s aft launch tubes. The fleet arrived in Genoa in the evening.

Duca D’Aosta in drydock in 1948, before transfer.

Post-armistice and co-belligerence period (Sept. 1943 – May 1945);

The surrendering Italian fleet was bound for Malta and the Battleship Roma sunk underway. Admiral Oliva was in disagreement with Bergamini about the armistice clause and the latter was warned by telephone by De Courten to depart anyway. After internment, Duca D’Aosta stayed inactive until the allies accepted co-belligerence and the fleet was supplied. Maintenance work was done at Taranto Arsenal, in October 1943. The cruiser under command of Captain Ludovico Sitta from 18 April 1944 carried out 24 missions over 31,330 miles until V-Day. She patrolled the central Atlantic (seven patrols), together with Garibaldi and Duca degli Abruzzi, searching for blockade runners and U-Boats operating along the coast down to Freetown. From April 1944, she transported troops, making 55 missions over 61,542 miles.

En route to USSR

Later life as Kerch:

In compliance with peace treaty clauses Duca d’Aosta was ceded as war reparations to USSR, in addition to Giulio Cesare, the training ship Cristoforo Colombo, destroyers Artigliere and Fuciliere, torpedo boats Animoso, Ardimentoso and Fortunale, submarines Nichelio and Marea, destroyer Riboty and many other ships. Due to the poor maintenance of many, economic compensation was granted instead. Like other, D’Aosta was to be dlivered after restoration works at the Arsenal of La Spezia.

The cruiser Kerch in 1950. She had her decks repainted in orange-red, the hull dark grey with a thing white line above the waterline, the former name was removed and the now one plated over.

Delivery took place between December 1948 and June 1949 and she was in the second group with flag exchange in the port of Odessa, and she was given the provisional ‘Z 15’ pennant as delivered to the Soviet Navy on March 2, 1949. Captain Semën Michailovič Lobov took command (a fleet admiral in 1970). D’Aosta war flag was sent in Rome, and now preserved at the Sacrario delle Bandiere del Vittoriano. Name Kerch, she was withdrawn from active service on February 7, 1956, ending as a training ship until May 11, 1958, then experimental “OS 32” hull for firing trials. Stricken on February 20, 1959 she was BU in 1961.

Eugenio di Savoia

NSM (Nave di Sua Maestà) Eugenio di Savoia was laid down in 1933 in Ansaldo shipyard, Genoa, launched 1935, commissioned 1936 as the very last of the class. During the late interwar after a short shakedown cruise and fixes, training, she went for her first mission to the Spanish coast, to watch over Italian citizens and interests during the civil war. In 1938 she was pressed with her sister by Mussolini for a circumnavigation of the globe, delayed and then interrupted by the outbreak War while she off south america. Under her first captain Massimiliano Vietina from January 1936, replacing “completion captain” Ludovico Sitta from September 3, 1935. But in September 1939, and since late 1938 this was Antonio Muffone, replaced by Carlo De Angelis in 1940. With Duca d’Aosta, Montecuccoli and Attendolo she was part of the VIIth Cruisers Division, IInd Squadron in La Spezia under Adm. Luigi Sansonetti.

Eugenio di Savoia in 1941. During the early war, she spent her service time escorting convoys and laying minefields.

Her career mirroed he sister’s: On 9 July 1940 she took part in the battle of Punta Stilo and later with Montecuccoli and five destroyers she shelled Corfou in December 18, 1940 during the attempted Italian invasion of Greece. By 12-16 June 1942, she was at the battle of Pantelleria (Operation harpoon) as flagship of Admiral Da Zara, and with Montecuccoli, she sank HMS Bedouin, finished off by torpedoes from an S.M.79. She also burned the large tanker Kentucky, already hit by Stukas. Next, on 10-15 August she took paert in what the Italians called “the battle of mid-August” (Operation Pedestal).

She was moored in Naples on 4 December 1942 during the infamous “Santa Barbara’s raid”, hit by bombs from B-24 Liberator. One hit caused heavy damage to the aft hull. Repairs were estimated to be about 40 days. The crew deplored 17 dead and 46 injured. Montecuccoli was also badly hit and took seven months of repair, while Muzio Attendolo was a total constructive loss.

Back in service, in January 1943 Eugene of Savoy shot down two enemy bombers.

At the armistice of 8 September she had been moved in La Spezia. Assigned to the VII Division, she departed for Internment in Malta. flanked by Attilio Regolo and escorting the battleships Roma, Vittorio Veneto and Italia (IX Division) the XII Sqn and XIV Sqn destroyers and several TBs they met en route another fleet from Genoa (VIII Division: Garibaldi, Duca degli Abruzzi Duca d’Aosta) and later joined by those from Taranto. Duca d’Aosta while en route was reassigned to the VII Division, replacing Attilio Regolo to pair with her sister Eugenio di Savoy (flagship of Admiral Romeo Oliva). Roma (flagship of Carlo Bergamini) sank on 9, attacked by Dornier Do 217s with guided bombs and in replacement, Oliva took command of the fleet until reaching destination on September 11. Afterwards, the fleet was dispatched again and D’Aosta interned in Alexandria. Until that time, she carried out 25 war missions covering 25,000 miles.

Savoia in 1942 Flickr. src Paizis-Paradellis (2002). Hellenic Warships 1829–2001 (3rd Edition). Athens, Greece: The Society for the study of Greek History. pp. 64–65. ISBN 960-8172-14-4.

On 13 October, cobelligerence started and after a refit and some maintenance in Italy, she return to guard the Suez area, taking part in an allied objective, notably with mock air attacks. On 29 February 1944 while returning from Suez she hit a mine off Punta Stilo and was severely damaged. She limped back to reach Taranto and remained there unrepaired until V-Day.

Postwar career: as Greek Elli

After the end of the war she had a long overhaul on June 26, 1951, sold as reparation for war damage to Greece, renamed Elli in memory of the light cruiser sunk by Delfino on August 15, 1940 near Tino Island. As the largest active ship after the old Averoff (Italian buult), she became the new flagship, carrying King Paul I of Greece to Istanbul for a state visit in June 1952, Yugoslavia in 1955, Toulon or Lebanon. In 1959 she was in Suda, Crete, as Ionian fleet command ship. She was used for trainined and decommissioned in 1965, but not BU. Instead she became a prison ship during the colonel’s regime in the 1970s, sold for BU in 1973.