Category: ww2 Italian Navy

Marconi class Submersible

Oceanic Submersibles: 1939-40: Alessandro Malaspina, Leonardo da Vinci, Luigi Torelli, Major Baracca, Michele Bianchi, Guglielmo Marconi. The Marconi class were…

Folgore class destroyer (1931)

Regia Marina: 8 Built 1929-33: Folgore, Lampo, Fulmine, Baleno The Folgore class, sometimes mixed with the Dardo class, was composed…

Liuzzi class submarine (1939)

Oceanic Submersibles: 1939-40: Console Generale Liuzzi, Alpino Bagnolini, Reginaldo Giuliani, Capitano Tarantini. The Liuzzi class were four submersibles all built…

Freccia class destroyer

Regia Marina: 8 Built 1929-33: Italy: Dardo, Frecchia, Saetta, Strale Greece: Hydra, Spetsai, Psara, Kountouriotis The Freccia (or Dardo) class…

Brin class submarine (1938)

Oceanic Submersibles: 1938-39 Brin, Benedetto Brin, Galvani, Guglielmotti, *Archimede, *Torricelli The Benedetto Brin class were a repetition of Archimede class…

Navigatori class Destroyer

Regia Marina: 12 Built 1928-31: Alvise Da Mosto, Antonio da Noli, Nicoloso da Recco, Giovanni da Verrazzano, Lanzerotto Malocello, Leone…

Marcello class submarine

Oceanic Submersibles: Lorenzo Marcello, Enrico Dandolo, Sebastiano Veniero, Andrea Provana, Lazzaro Mocenigo, Giacomo Nani, Agostino Barbarigo, Angelo Emo, Francesco Morosini,…

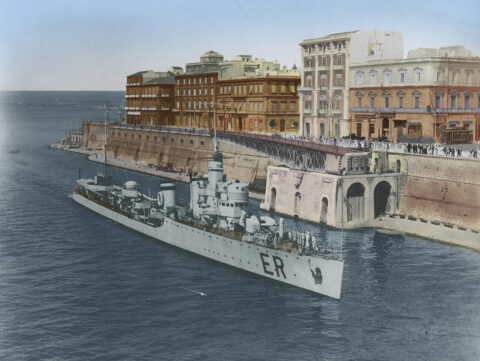

Turbine class destroyer

Regia Marina: 8 Built 1925-1928, all lost in action before Sept. 1944: Aquilone, Borea, Espero, Euro, Nembo, Ostro, Turbine, Zeffiro…

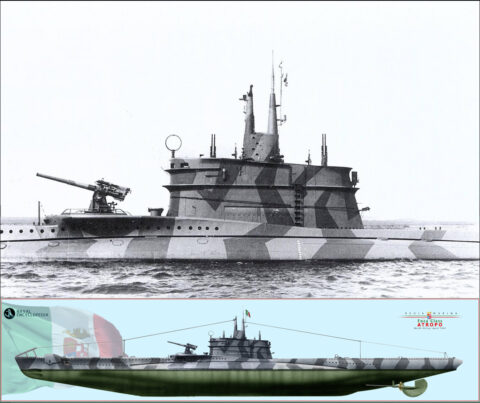

Foca class submarine

Minelaying Submersibles: Foca, Atropo, Zoea (1936-47) The Foca class were three minelaying submarines (sommergibili posamine) of the Regia Marina, sister…

Sauro class Destroyer

Regia Marina -4 destroyers: Cesare Battisti, Daniele Manin, Francesco Nullo, Nazario Sauro. Built 1925-1927, interwar, ww2, 4 lost. The Sauro…

dbodesign

dbodesign