Category: ww1 naval battles

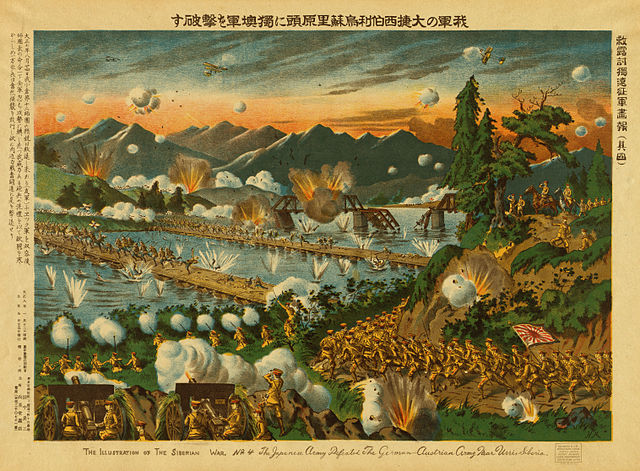

Battle of Tsingtao (August-Nov. 1914)

Japanese Navy vs German Navy Introduction: The first air-land-sea battle The battle of Tsingtao was one of these twists of…

Battle of Elli and Lemnos (1912-13)

Greek Navy vs Turkish Ottoman Navy The Battles of the Aegean sea, a prelude to the great war at sea…

Armistice and consequences

The end of the war to end all wars Today, 11 November 2018, we remember the sacrifice of an entire…

Battle of Imbros (20 January 1918)

Turkish Ottoman Navy vs Royal Navy The end of the Ottoman fleet Before the Autro-Hungarian Navy was condemned to inaction…

Second Battle of Heligoland (17 November 1917)

Kaiserlichesmarine vs Royal Navy A missed second Jutland The island of Heligoland, at the outposts of the German coast, was…

Battle of Moon Island (October 1917)

Russian Navy vs German Navy This action took place in the Baltic Sea between Russian and German units as part…

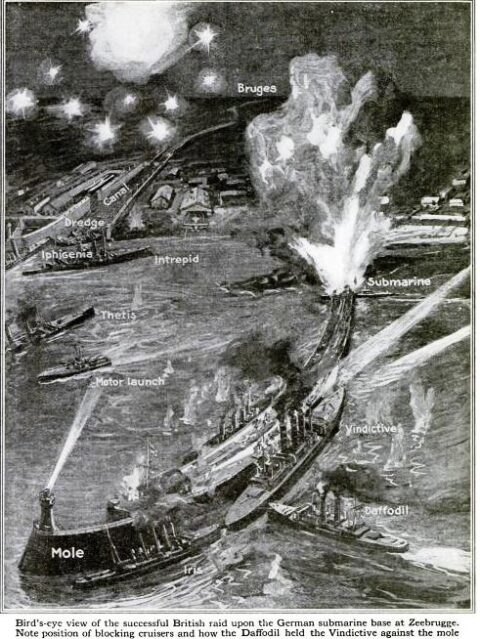

Zeebruge Raid (April, 23, 1918)

United Kingdom vs. Germany, 23 April 1918 The Zeebrugge Raid on the northern, Flemish coast remains one of the most…

Otranto Strait Battle (May, 15, 1917)

Forcing the Barrage The famous Barrage of Otranto (Authors’ map) The strait of Otranto, between Corfu and Brindisi, which is…

Dover Strait Actions – October 1916 to April 1917

For the Control of the Channel Dover strait, which commands the southern Atlantic passage for the German Navy. The first…

The torpedoing of Lusitania – May 7, 1915

Above: The position of Lusitania during its sinking After the famous Titanic, sunk in peacetime, the sinking of the Lusitania…

dbodesign

dbodesign