Category: ww2 warships

Canadian Tribals (Iroquois class) (1941)

Royal Navy (built 1940-47) Iroquois, Athabaskan, Huron, Haida, Micmac, Nootka, Cayuga, Athabaskan (II) Canada Day ! The Canadian Navy had…

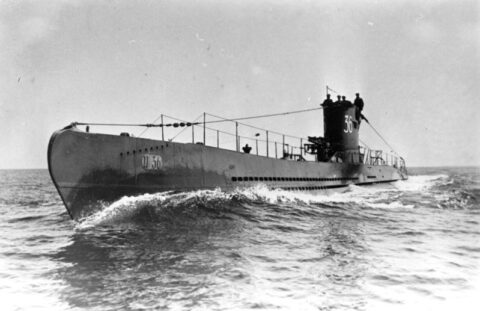

Type VIIA (1933)

Kriegsmarine (1934), U-26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 With the Type VIIA we start a…

J- K- N- class destroyer

Royal Navy (24 built 1937-41) J class: Jackal, Jaguar, Janus, Javelin, Jersey, Jervis, Juno, Jupiter K class: Kandahar, Kashmir, Kelly,…

Yūgumo class destroyer

IJN 1st class Destroyers built 1940-44: Yūgumo, Makinami, Hayanami, Hamanami, Okinami, Hayashimo, Kazagumo, Takanami, Kiyonami, Suzunami, Kishinami, Kiyoshimo, Makigumo, Naganami,…

Type 1939 Torpedo Boat

Germany (Kriegsmarine): 1942–1944: T-22 to T-36 The Type 1939 torpedo boat or Flottentorpedoboot 1939 (also known by the German designation…

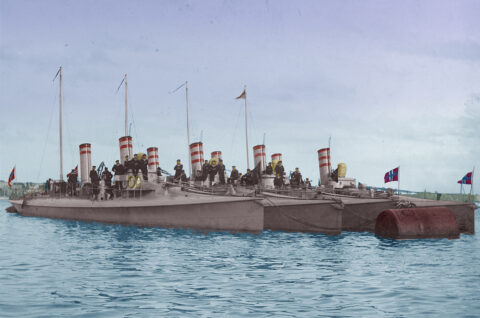

Hval class Torpedo Boat (1896)

Sjøforsvaret, Torpedo Boats (1896-1900): HNoMS Hval, Delfin, Hai, Trods, Storm, Brand, Laks, Sild, Sael, Skrei 1896-1901 This class of ten…

Tribal class Destroyer (1937)

Royal Navy (built 1936-39) British Tribals: Afridi, Ashanti, Bedouin, Cossack, Eskimo, Gurkha, Maori, Mashona, Matabele, Mohawk, Nubian, Sikh, Somali, Tartar,…

Kagerō class Destroyer

IJN 1st class Destroyers built 1938-41: Kagerō, Shiranui, Kuroshio, Oyashio, Hayashio, Natsushio, Hatsukaze, Yukikaze, Amatsukaze, Tokitsukaze, Urakaze, Isokaze, Hamakaze, Tanikaze,…

Type 1937 Torpedo Boat

Germany (Kriegsmarine): 1940–1944: T-13 to T-21 Development The Type 37 torpedo boat was a class of nine torpedo boats built…

I class destroyer

Royal Navy (1936-38) I class: Icarus, Ilex, Imogen, Imperial, Impulsive, Inglefield, Intrepid, Isis, Ivanhoe, Inconstant*, Ithuriel*. The I-class destroyers were…

dbodesign

dbodesign