Category: WW1 French Navy

Courbet class Dreadnought Battleships (1911)

France (1911) – Courbet, Paris, France, Jean Bart (ex-Ocean) France’s first dreadnoughts The Four Courbet class were the first French…

Danton class Battleships (1909)

France (1909) Condorcet, Danton, Diderot, Mirabeau, Vergniaud, Voltaire The six Dantons were the last French pre-dreadnoughts. They had the misfortune…

Ernest Renan (1906)

France. Armored Cruiser built 1904-1908, service until 1937. Ernest Renan was the penultimate French armored cruiser, launched the same year…

Jules Michelet (1905)

France. Armored Cruiser built 1904-1908, service until 1937. Jules Michelet was an evoliution of the previous Leon Gambetta armoured cruiser…

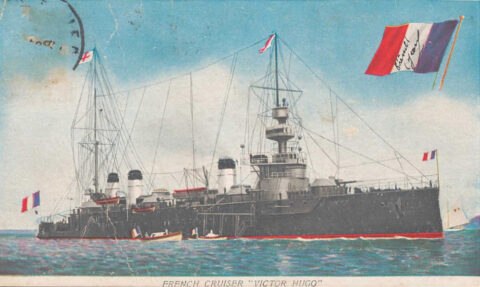

Léon Gambetta class Armoured Cruiser (1902)

France. Built 1901-1907, service until 1928: Armored Cruiser Léon Gambetta (1903), Jules Ferry (1903), Victor Hugo (1904). The Léon Gambetta…

République class Battleships (1904)

French Navy Pre-Dreadnought Battleship: FS République, Patrie (1901-1905) The many shortcomings of the previous classes, born under the Jeune Ecole…

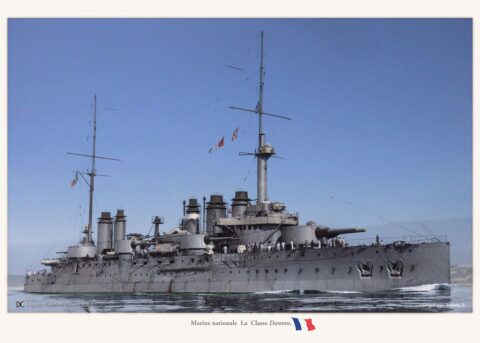

Dupleix class Armoured Cruisers (1900)

France (1899-1927) – Armored Cruisers: Dupleix, Desaix, Kléber The Dupleix class consisted armored cruisers of the Marine Nationale were designed…

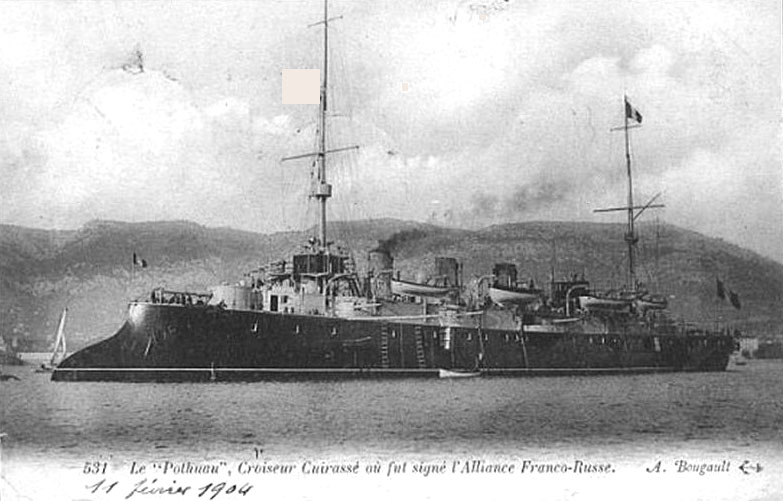

Armored Cruiser Pothuau (1895)

France (1893-1927) – Armored Cruiser The French Armoured cruiser Pothuau was built in the 1890s as a one-off derivative of…

Gloire class Armoured Cruisers (1900)

Marine Nationale, 1899-1954: Gloire, Marseillaise, Sully, Amiral Aube, Condé The Gloire class consisted of five armored cruisers built for the…

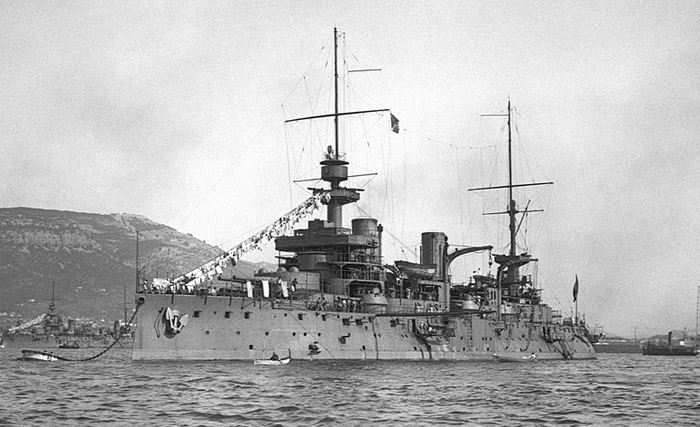

French Battleship Suffren (1899)

French Navy Pre-Dreadnought Battleship (1899-1916) Design of the class The Suffren was the last “classic” French pre-dreadnought. The next Republique…

dbodesign

dbodesign