Category: ww1 german navy

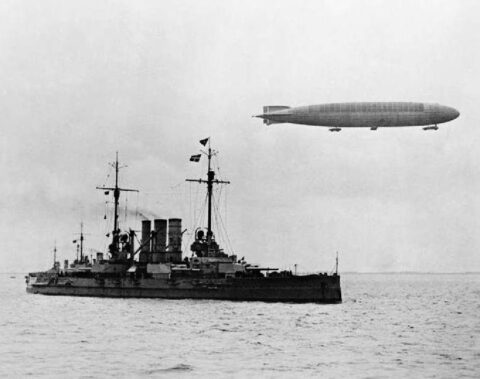

Helgoland class Battleships (1909)

Germany (1912) Helgoland, Ostfriesland, Thüringen, Oldenburg The Helgoland class Battleships were very similar to the previous Nassau, first generation of…

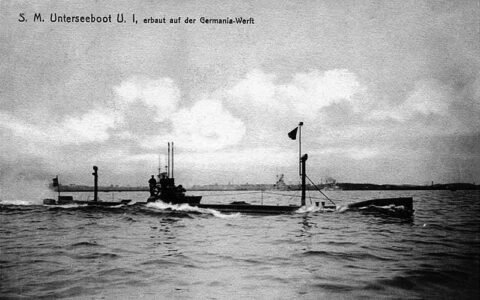

U1 (1906)

German Empire (1906-1919, preserved 1921) Experimental U-Boat The first U-Boat The path towards 1914 U-Boats started somewhat later than other…

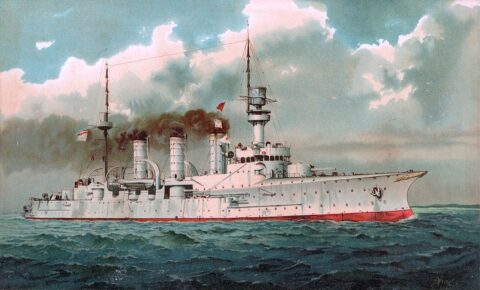

Victoria Luise class Protected cruisers (1897)

German Empire (1896) Victoria Luise, Freya, Vineta, Herta, Hansa The first Class of German Protected cruisers: The second class of…

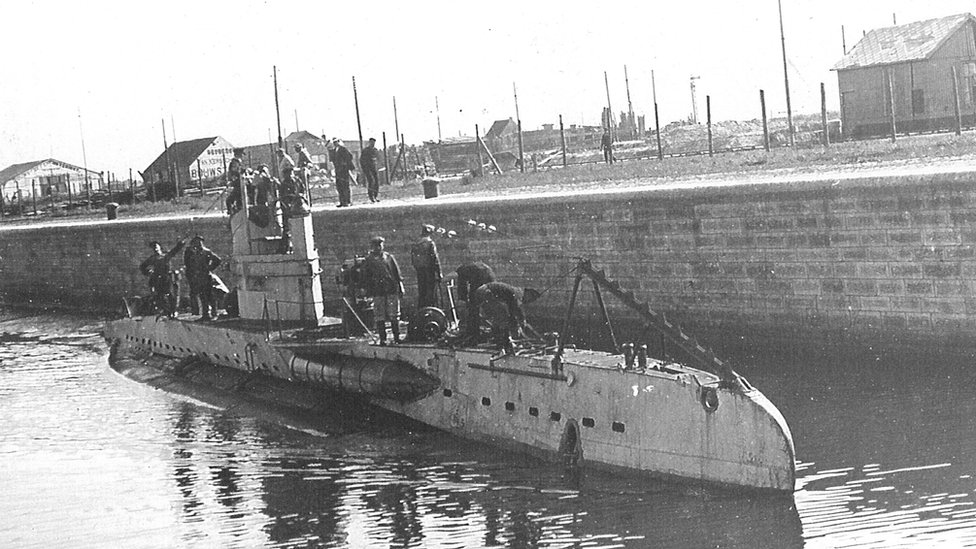

UB-III class submersibles (1916)

German Empire – 200 submarines, 96 comp. UB-48 to UB-155 The UB-III became the mainstay of the the German submarine…

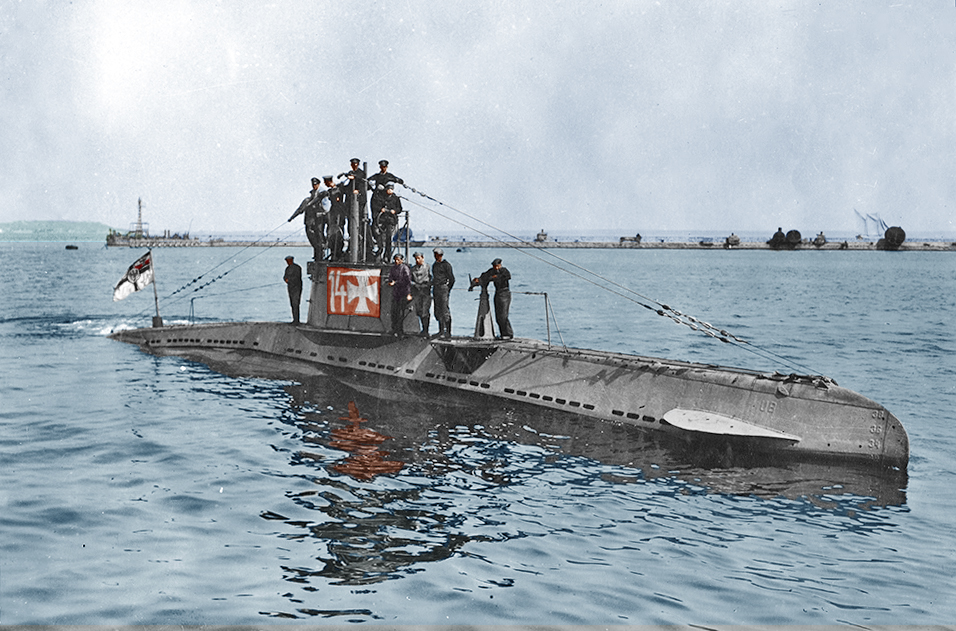

UB-II class submersibles (1915)

UB-2 class (1915-18) German Empire – 30 submarines, UB-18 to UB-47 UB-45 underway in 1916 The UB-II class. Second part…

UB-1 class submersibles (1914)

UB-1 class (1914-18) German Empire – 20 submarines, UB-1 to UB-17, Austro U-10 to U-17, SM UB-3 to UB-14 The…

Cöln class cruisers (1916)

Germany: SMS Cöeln(ii), Dresden(ii), Wiesbaden(ii), Magdeburg(ii), Leipzig(ii), Rostock(ii), Frauenlob(ii), Ersatz Cöln, Ersatz Emden, Ersatz Karlsruhe (1916-1919) Coeln class cruisers 1916:…

Königsberg (ii) class cruisers (1915)

Germany (1914-1920) – SMS Königsberg, Karlsruhe, Emden, Nürnberg The replacement cruisers Painting of the Karlsruhe in Scapa Flow A new,…

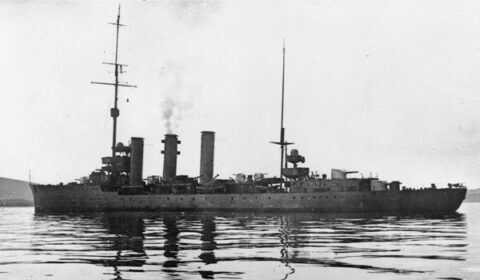

Wiesbaden class cruisers (1915)

Germany – SMS Wiesbaden, SMS Frankfurt (1914-1919) Hipper’s Cavalry: Among the light cruisers screening for the Kaiserliches Marine, were the…

Brummer class cruisers (1915)

Germany (1913-1919) – SMS Brummer, Bremse In 1915, the Admiralty decided to start construction in Vulcan, Stettin, of two large…

dbodesign

dbodesign