Category: 1860 fleets

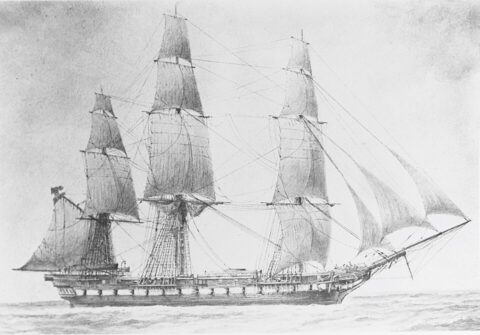

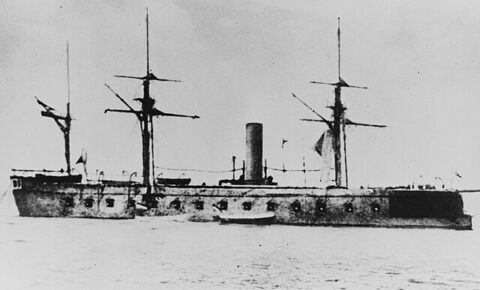

Schwarzenberg (1853)

Austrian Navy Sail & Steam Frigate 1854-1890 SMS Schwarzenberg was an Austrian Navy Frigate built in Venice in 1851-54 and…

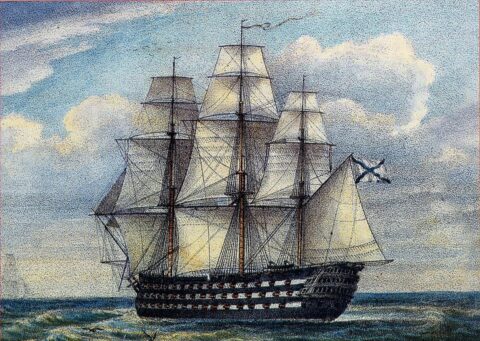

Dvienadsat Apostolof Class

120-gun, 1s rate ships of the line: 12 Apostles, Paris, Grand Duke Constantine 1838-1855 The Dvienadsat Apostolov (12 apostles) were…

Gloire class ironclads (1859)

France 1858-1880, Broadside Ironclad Origin of the ironclad concept The naval staff under the 2nd French Empire (Napoleon III) was…

HNLMS De Ruyter (1863)

Dutch Netherlands Navy: 74 guns 2nd rate, 54 guns Razee, 51 guns steam Frigate, Casemate Ironclad, 1831-1874 HNLMS De Ruyter…

Erzherzog Ferdinand Max class (1863)

Austrian Navy, 1862-1883: SMS Erzherzog Ferdinand Max, Habsburg The Erzherzog Ferdinand Max and Habsburg were built for the Austrian Navy…

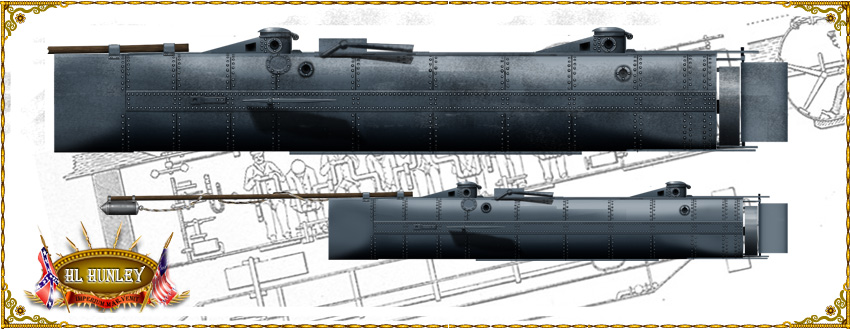

HL Hunley (1863)

Confederate Navy (1863) Single prototype, following Pioneer and American Diver 1861-63 So many books and documentaries, even featured films were…

Kaiser Max class ironclads (1862)

The broadside ironclads with a double life Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1862-1883: SMS Kaiser Max, Juan d’Austria, Prinz Eugen Austrian Fleet |…

Drache class ironclads (1860)

The first Austro-Hungarian Broadside ironclad Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1862-1883: SMS Drache, Salamander Austrian Fleet | pre-WW1 fleet | WW1 fleet The…

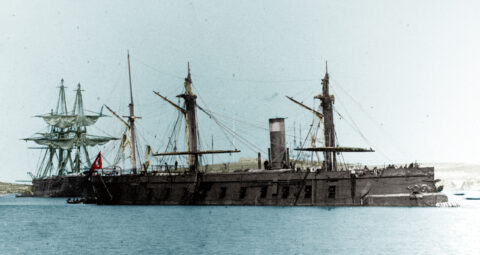

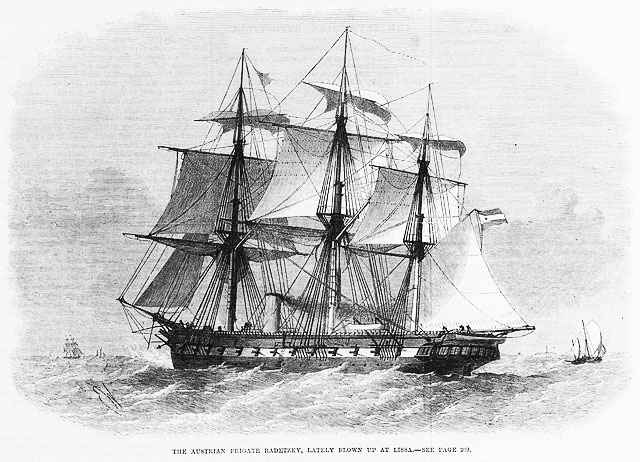

Radetzky class Frigates (1854)

Austrian Navy 1854-88: SMS Radetzky, Adria, Donau Design In 1852, the Austro-Hungarian Navy’s high command proposed the construction of a…

Novara class steam Frigates (1853)

Novara class Steam Frigates (1857) Austro-Hungarian Navy 1843-1900, SMS Novara, Schwarzenberg The Novara class was one of two largely similar,…

dbodesign

dbodesign