Category: ww1 german navy

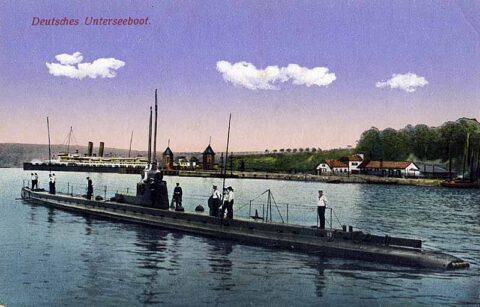

U23 class (1912)

Germany: SM U23, 24, 25, 25 (1912) The U23 class submarine were of the so-called double-hulled type, designed as oceanic…

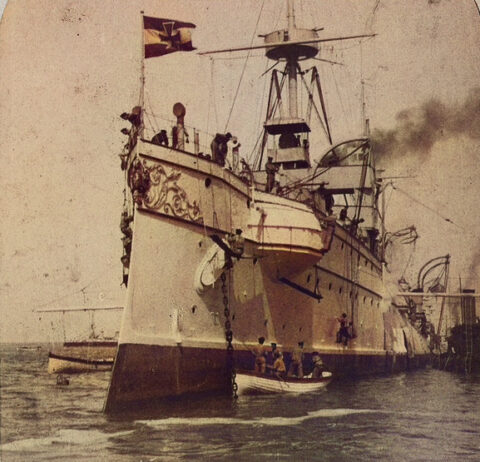

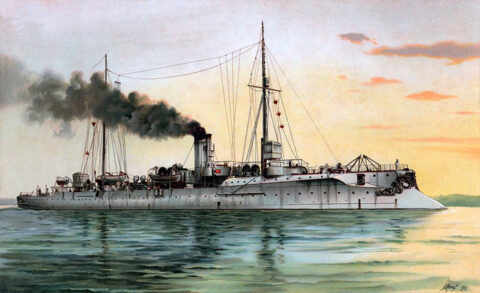

SMS Hela (1895)

Germany, Aviso-Cruiser, 1895-1914 SMS Hela was a cruiser of the Imperial German Navy, initially classed as an “aviso” (despatch vessel)….

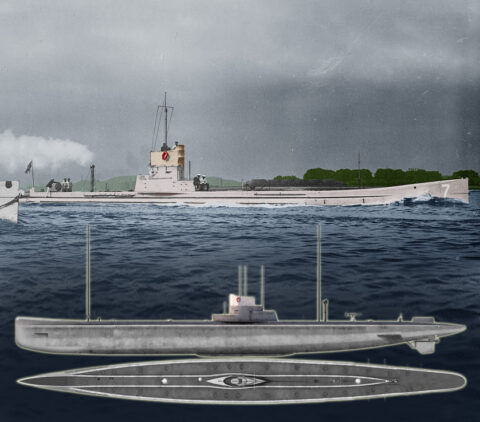

U19 class (1912)

Germany: SM U19, 20, 21, 22 (1912) The U19-22 series were the first German U-Boat class fitted with diesel engines…

U13 class (1911)

Germany: SM U13, U14, U15 (1909-1912), U16 (1911). Class U17: U17, U18 (1912) The U 13 class (U 13, 14,…

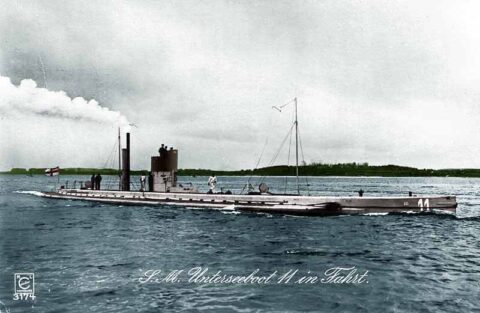

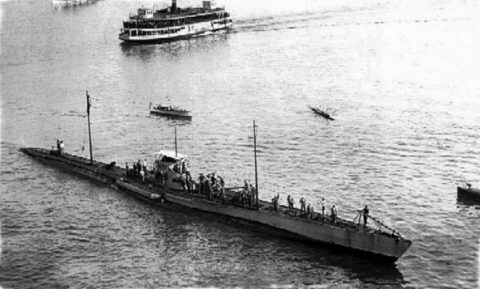

U9 class (1910)

Germany: SM U9, U10, U11, U12 (1910-1911) The U9 was the first in a series of four submersibles built at…

U5 class (1910)

Germany: SM U5, U6, U7, U8 (1910-1915) Development The short-lived U5 class was a simple evolution of the U3 class…

U3 class (1909)

Germany: SM U3, U4 (1908-1909) Development SM U-3 was the third German U-boat, at a time the head of staff…

UC-III class submersible (1918)

German Empire – 113 submersible planned, 25 comp.* UC-90 to UC-114 Type UC III minelaying submarines were designred and built…

U31 class U-Boats (1914)

Germany (1913-1919) U-31 to U-41, launched/commissioned 1914-15 U 31 class subs. Fourth entry after U1 and the UB series. The…

dbodesign

dbodesign