Category: ww2 warships

I class destroyer

Royal Navy (1936-38) I class: Icarus, Ilex, Imogen, Imperial, Impulsive, Inglefield, Intrepid, Isis, Ivanhoe, Inconstant*, Ithuriel*. The I-class destroyers were…

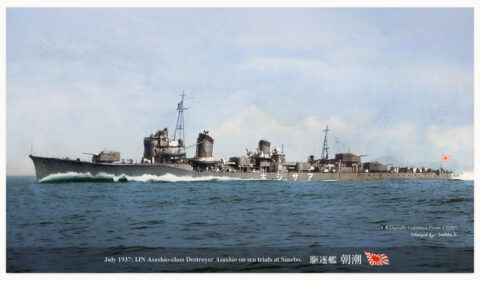

Asashio class Destroyer

IJN “special type” Destroyers built 1937-39: Asashio, Ōshio, Michishio, Arashio, Asagumo, Yamagumo, Natsugumo, Minegumo, Arare, Kasumi. After a time of…

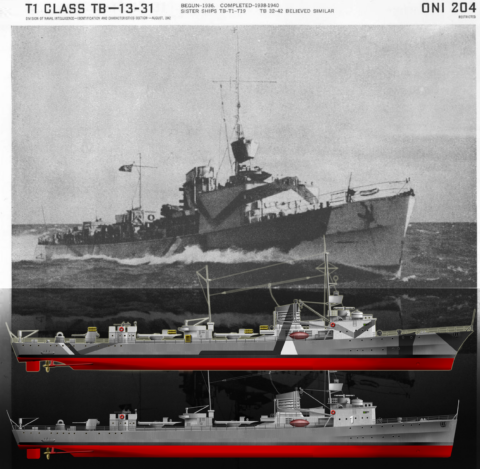

Type 1935 Torpedo Boat

Germany (Kriegsmarine): 1938–1940: T-1 to T-12 Development The Type 35 torpedo boat were the first modern German Torpedo Boat type,…

Type-XVII U-Boat

Germany (1944), Coastal Subs, 16 planned, 7 completed The Type-XVII U-Boat was the only attempt of the Kriegsmarine to run…

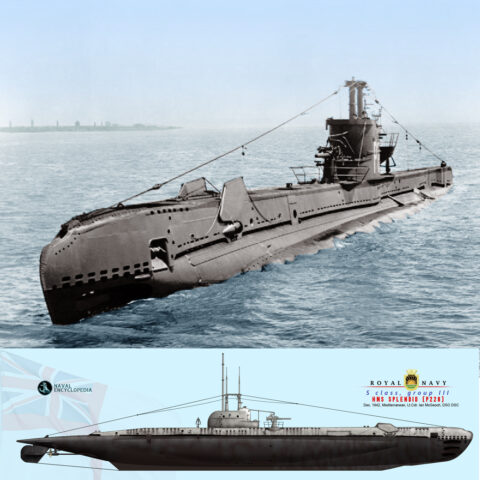

S class submersibles (group III) 1939-43 Programmes

Light Submersibles 1932-1945: S-class Group III: 50 +11 cancelled, War Emergency Programmes 1939, 1940, 1941, 1942, 1943, built 1940-1945 The…

G/H class destroyer

Royal Navy (1930-34) G class: Gallant, Garland, Gipsy, Glowworm, Grafton, Grenade, Grenville*, Greyhound, Griffin H class: Hardy, Hasty, Havock, Hereward,…

Shiratsuyu class Destroyer

IJN “special type” Destroyers built 1931-35: Shiratsuyu, Shigure, Murasame, Yūdachi, Harusame, Samidare, Umikaze, Yamakaze, Kawakaze, Suzukaze. The conditions imposed by…

Type 24 torpedo boat

Germany (Reichsmarine): 1925-28: Wolf, Iltis, Jaguar, Leopard, Luchs, Tiger The Type 24 torpedo boat (or Raubtier class (‘Carnivorous’) were six…

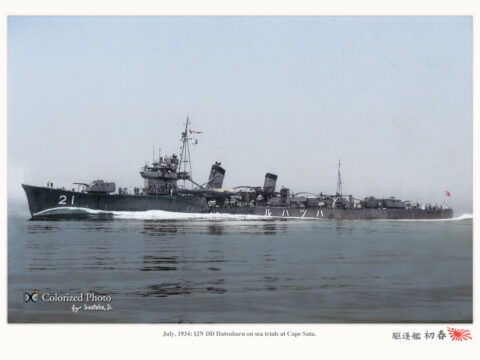

Hatsuharu class destroyer

IJN “special type” Destroyers built 1931-35: Hatsuharu, Nenohi, Wakaba, Hatsushimo, Ariake, Yūgure The Hatsuharu-class destroyers (Hatsuharugata kuchikukan) were the next…

Loch class Frigates (1942)

United Kingdom – (1943-45): 110 planned, 28 completed, 26 to Bay class, 54 cancelled. The Loch class were anti-submarine warfare…

dbodesign

dbodesign